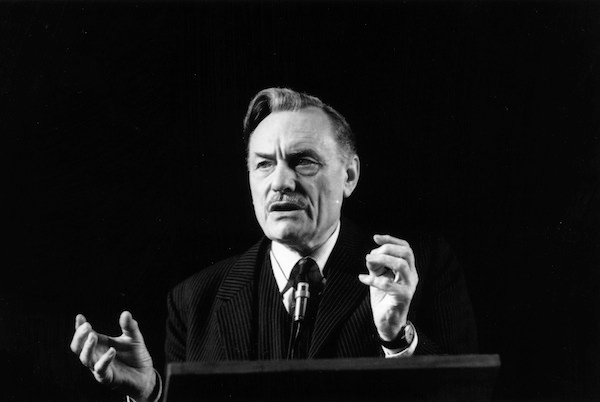

One of the great tragedies of political history is that the foresight, clarity and prescience of Enoch Powell are too often viewed though the murky prism of his notorious Rivers of Blood speech. His kindness, courtesy, love of his family, nation and the House of Commons can be so easily overlooked. And his dry and sometimes mischievous sense of humour almost ignored.

Enoch at 100 is a wonderful and accessible book which gives us a fair and accurate perspective of the man that so many of us genuinely liked and respected. It is a compilation of personal anecdotes by those who knew him well and others who give real insight into a man whose scarily logical mind was well ahead of its time.

The anecdotes, particularly, by his wife Pamela, are both moving and revealing. In the modern age of twenty-four-hour media coverage it is almost incomprehensible that when he made that fateful speech in Birmingham his Wolverhampton home possessed neither a television nor a telephone. He had to drive to the constituency office to be told that Ted Heath wanted to see him, followed by the long drive back to London for the sacking.

Pamela Powell nails the lie that he was a racist and didn’t like foreigners:

‘Well, I always think of General Carriappa, when people say that. Nowadays, what I’m about to say sounds completely normal and unexceptional, but at that time in India, it certainly wasn’t. Enoch was secretary of the All Indian Army Committee and he and the General were going around most of India, this was after the war…..until he was demobbed in 1946. They stopped at the Byculla Club, in Pune and the club said that the Indian gentleman, who was General Carriappa, couldn’t come in because they didn’t have anybody except white people here. So Enoch said, ‘take my baggage out of this club, I am going to stay with my friend General Carriappa’. And he did.’

I have many happy memories of Enoch. When I was elected in 1983 I, like everyone else, had to wait months before being allocated a cramped and shared office. So I found a wonderful octagonal desk in the library, complete with silver Pugin inkwells, and plonked myself down. I didn’t appreciate that this was the great man’s perch. But he was charm itself and allowed me to sit opposite him until I ended up sharing with five others in what eventually became Gerry Adams’s suite. At one time we appeared together on Any Questions. Sadly, the programme was taken off air for a few minutes as we were water-bombed by a baying mob. And on another occasion, I was asked to stand in for Ken Clarke at the Oxford Union. Ken was Health Secretary at the time and the unions were in uproar. I found myself sitting next to Enoch on the train up. As we walked from the station I could hear the bayings of another mob. ‘How on earth do you put up with this?’ I asked. Enoch just smiled. ‘My dear Jerry, listen carefully. They are not demonstrating against me. It is you. I am off for dinner with a friend’. And, with a twinkle in his eye and a smile, he raised his black homburg in farewell and walked off into the night, leaving me to my fate.

Anne Robinson tells an interesting tale about his thoughtfulness. She was presenting a live television show with Enoch as the guest. She went up to him (he was speaking to Ann Leslie in Swahili at the time) and told him that she had taken his advice to present the programme on a half-full bladder as she was petrified. When she had finished her opening remarks he turned to her, off camera, grinned and gave her the thumbs up. It calmed her nerves considerably.

One of the most fascinating chapters in this book is Simon Heffer’s analysis of Powell’s economic philosophy which was decades before its time.

‘When Milton Friedman won the Nobel Prize in economics in 1976 Enoch Powell observed, only half in jest, that he should have had half of it. Powell, felt with some reason, that he had put monetarism into practice twenty or so years before Friedman expounded his theory…..In 1957, when Powell was Financial Secretary to the Treasury…..he had worked out that inflation was caused by expanding the money supply at a rate faster than that of inflation and growth combined.’

Of course Harold Macmillan disagreed and the whole Treasury team resigned. It was also in the ‘50s that Powell propounded the theory of low taxes and privatising the hopelessly inefficient nationalised industries.

But it was not just his vision, but the clarity of his language which is still stunning. This is what he said about the consequence of Britain joining the EEC.

‘A common currency means common government; the one is meaningless and impossible without the other. Accept common money and you have accepted common government ….If one threatens to diverge what happens? …..they order it to alter its ways and dictate to it how to do so. Who then is doing the dictating? Where will be that common government which a common currency implies?……France and Germany, who hatched and willed this business, will see to it that they rule the roost: a Franco German hegemony , as France intends, or a German hegemony….All this has nothing to do with common markets or freedom of trade or all the alleged ideals of the EEC. Quite the reverse. This is not about freedom; it is about compulsion.’

And finally on the reform of the House of Lords, which he and his great friend Michael Foot defeated in 1968:

If Powell had been in the House of Commons today what would he have made of it? I suspect his words spoken in October 1987 are as valid today as then.‘There can be no elective second chamber in the legislature of a unitary state. Wherever elective second chambers exist, they exist in federal states, where one chamber represents the component parts as such, and the other chamber represents the whole population, as such. The classic case is the United States. The proposition is axiomatic, because it is self-evident that there cannot be two alternative equally valid representations of the same electorate. If one is more valid than the other they cannot co-exist: for where a more valid representation exists, there is just no justification for paying attention to a less valid representation. ‘A few simple theorems are sufficient. Suppose in a unitary state like the UK, one chamber is elected by a simple majority (like the House of Commons) and the other chamber by some variety of proportional representation. Which is to prevail? The simple majority chamber says: ‘No it is we who represent the people: you are only a caricature and a distortion.’ One chamber must destroy the other and no constitutional device or convention will avert that.’

‘I imagine that it has been the common experience of everyone who spent a great part of a lifetime in politics that at the end he was like some traveller having journeyed on from day to day, finds himself at last in a strange country, where the landscape is no longer recognisable and the people speak in a foreign tongue.’

This is a book that should be read by anyone interested in politics. It accurately portrays a man with a vision so far ahead of his time that he was regarded as a menace by the charming thuggery of the ruling elite. I sometimes wonder if that notorious speech, which resonated with so much of the country, had been denuded of some of the offensive language, whether Powell might have become Prime Minister. Of course. But would he have done? Of course no t. He was a man who lived solely by his principles.

Comments