Mick Jagger, the Danny La Rue of rock, impersonates a woman on the cover of the 1978 Stones album Some Girls. Vaudeville performers in the Jagger mould love to put on lipstick and ‘false bubbies’ (as Neil McKenna calls them). Boy X-Factor contestants, with their shaved eyebrows, diamond earrings and nails lovingly manicured, present an almost Gloria Swanson-like image of adornment.

Perhaps it is merely romantic to suggest that the stylised wigs and gowns worn by our bishops and high court judges also have a homoerotic component. The former Pope Benedict XVI’s ruby-red pumps were nothing compared to the faux ermines worn in the House of Lords.

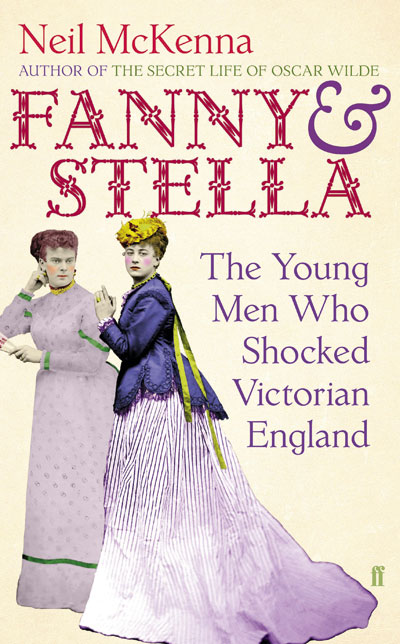

Frederick ‘Fanny’ Park, a judge’s son, and Ernest ‘Stella’ Boulton, were Victorian-era transvestites who lived large and lurid on the streets of London. Stella, the more presentable of the two, liked to flounce up and down Burlington Arcade on the lookout for suitors. One of her admirers, Lord Arthur Clinton, was the godson of William Gladstone and known to frequent androgynes and hermaphrodites of one stripe or another.

In the Britain of that time, buggery carried a sentence of servitude for life (originally it had carried the death penalty). Unsurprisingly, the Metropolitan Police had been keeping tabs on the ‘he-she-ladies’ Fanny and Stella.

One night in April 1870, they swooped on them outside London’s Strand Theatre (a ‘Noted Shop for Tarts’, joked a contemporary). Bundled into a Black Maria, the pair were fingerprinted at the station and ordered to step out of their crinolines. Alone in their cell, they were then charged with the crime of buggery and forced to undergo finger-probing medical examinations. In time, the arrests led to further arrests; Lord Arthur and other ‘peers of the realm’ were implicated in a sex scandal that thrilled mid-Victorian Britain.

With elements of Carry On music-hall banter (‘It had crept up on her. It had taken her from behind, you might almost say’), Fanny and Stella vividly chronicles the scandal and its aftermath. To the modern eye, the efforts of the Victorian police in general to eradicate homosexuality look rather suspect; the constables working on the Boulton Park case seemed to protest too much.

The surgeon assigned to the case, James Paul, dilated the suspects’ anal apertures by means of a speculum he carried for the purpose. (Perverted sex inevitably perverted the shape of the anus, he believed.) Sodomitical practice, whether with mankind or beast, was Paul’s one consuming passion. He compensated for his own perceived ‘femininity’ through an over-exaggerated masculinity which, like a long-pent-up balloon, expressed itself in displays of sexual peculiarity involving quantities of glycerine.

Among the other cross-dressing ‘Mary-Anns’ under police investigation was the self-styled Comical Countess, who serviced clients on a mattress in low-rent Bloomsbury rooming houses. McKenna relates much of his story in tones of high-flown campery (‘Miss Fanny Winifred Park had drunk deeply from the cup of Venus’); it works well enough, though some readers may weary of the ‘chi chi man’ slang.

Notably, the author’s descriptions of flagellation, fellatio and ‘Slap-Bum polka’ (don’t ask), are not for the faint-hearted. Fanny and Stella is best read wrapped in brown paper, and then with smelling salts to hand. The book is that lewd.

Comments