Richard Cobb had many good friends, among them Hugh Trevor-Roper, who kept letters, and so made this selection possible. There must be many more letters, since the author was an inveterate correspondent at least from the 1930s. The wartime ones would be of greater historical interest than these, which are nearly all post-1967, many of them concerned with the essentially piddling subjects of university politics, pupils and personalities. Of course, these are foie gras and the sound of trumpets to persons connected with such things at Oxford and Cambridge, but the admirable publisher must be aiming at a larger audience than that, ignoring Cobb’s own repeated assertion that ‘nothing ever happens’ in Oxford.

He was not your average don. ‘One of the most eccentric figures of the university world,’ according to his obituary in Le Monde, and that meant both Great Britain and France. He was a French-English Janus, fired up with Gallic and John Bull prejudice in equal amounts, and ready to defend both in either language, opinionated almost to the point of frenzy.

I knew him slightly: not well enough to enlist in any of his vendettas, but close enough to sense the attraction of his personality for pupils and some colleagues despite his spluttering, goggle-eyed indignation, his tendency to fall over, and his curious smell: tobacco and booze, entendu, but something additional, more rank, unexpected from a married Salopian, perhaps; but in no way detracting from his magnetism as a teacher.

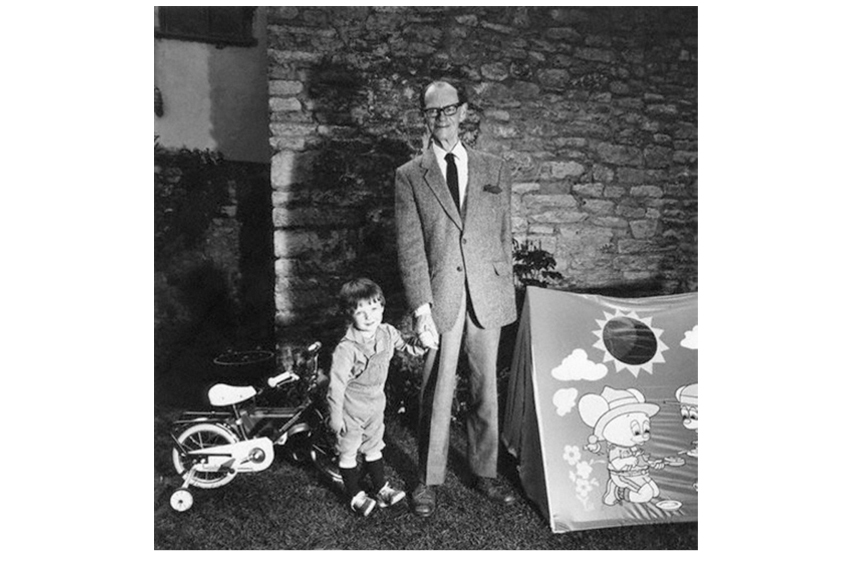

He was small, noisy, usually eager for human contact, and although he would deny it, sometimes charming and nearly always kind in conversation, if not in his letters. His works in English left me weak at the knees with admiration, whether they concerned Restoration and Napoleonic France or Tunbridge Wells before the war, mainly because of his eye for the telling detail of everyday life which reveals the inadequacy of the generalisation.

His empathy seemed limitless, reaching from the great Victorian historians Motley and Carlyle (‘sensational, though wickedly inaccurate’), to the varieties of home-coming businessmen arriving on the evening train at the suburb of his boyhood. His talent for observation and description make some of these letters memorable: the ‘Enoch Powell eyes’ of the inhabitants of Whitby (Boghole sous l’Abbaye), the ‘Farringdon millionairess’ Mrs Fleming, the ‘trendy miserabilist’ Graham Greene, the dyed hair of the communist Master of Balliol, and the ‘GRACELESSNESS’ of his college, where Cobb was a tutor for ten years and lost patience with the posturing Leftist dons and the pot-hunting students: ‘Balliol, bloody Balliol, has got SIX firsts. Disgusting.’ Harold Wilson, at a banquet, resembled ‘a gnome with the large head of an ageing and wicked child, wearing his garter on the wrong thigh.’

Other concerns revealed here were jobs (getting congenial or competent candidates into posts from which fashionable Leftist History Men had to be excluded, a task equally important to Trevor-Roper) and reviewing the books of other historians with as much cheerful vituperation as they deserved. He was not consistent in praise or censure. Schama was ‘admirable’ for his French Revolution book in May 1989, and ‘singularly graceless’ in June; Rowse was a ‘quite likeable’ cat-lover in 1986, but ‘very nasty’ in 1989, and Christopher Hill, ‘really very good’ as Master of Balliol to begin with, had become ‘in every way a bad Master’ ten years later. It was not that age or experience brought wisdom or enlightenment. Cobb was always prone to silliness, which he called his ‘essential frivolity’. He liked it in his friends and protégés, and distrusted gravity in anyone.

His loves and hates reverberate from letter to letter, ‘profound’ but ‘fluctuating violently’ as his editor warns us. The loves are mostly what gave him physical or aesthetic pleasure. The list includes Abbott’s Special beer, Cambridge pubs, ironing, pretty girls, London clubs, Merton college, fens and flat countries, Belgium minus Flemings, Ludlow, Eton, hedonistic and amusing pupils given to pranks and hoaxes, Frinton-on-sea and North Essex, NHS hospitals, Protestantism (minus teetotal Huguenots and Scotch Calvinists, but including the non-ritualist C of E), cats and the cooling month of October. To these add Robert Walpole and Stanley Baldwin, no more sources of sensual pleasure than various other approved right-wing leaders.

The list could be doubled or trebled by things he liked in France, but they don’t occur in these letters; and extended further by his craving for honorary degrees, hoods, gowns of many colours, and any available orders and decorations from the Crown or the Republic. It didn’t take much to win his love: a brief trip to Salamanca in old age, combined with a polite and attentive audience, made the Spaniards ‘about the nicest people in Europe’.

Nevertheless, the ‘hate category’ is just as large, even larger, viz. summer (mid, but especially August), Sofia, Vienna, the Cotswolds, the RAF, cricket, rugger, golf, dogs, ‘bleeding heart’ dons, the Balkans, Malvern, Winchester and most Wykehamists, Lithuania, ‘bloody thieving Catalans’, and other ‘abusive pseudo-nationalities’, i.e. Basques, Letts, Estonians, Slovaks, Ukrainians and their ‘sinister’ land, Kurds, Serbs, Palestinians, the Irish, Marxists, Communists, Catholics (‘but they do give you a decent drink’), muesli, Leopold III of Belgium, fruit juice, and any books that could be described as ‘complicated, vachement intellectuels, or about ideas’. He wouldn’t read Proust, admitted that he had only a ‘glimmering awareness’ of the English past, and came to abominate the French Revolution in all its aspects, especially the bicentenary celebration of 1989.

These flickering passions are compatible if not quite complementary, because they derive from his upbringing and wartime experience. He was a son of the empire (father usually in the Sudan), a ‘ruined boy’ of Shrewsbury school, a witness of the disintegration of France in the 1930s, and of the effects of the defeat and occupation. Much as he distrusted authority in all its forms, French or English, political or academic, he remained firmly committed to the national interest. He could not understand why the ‘unspeakable pseudo Count Tolstoy’ should persecute‘poor Lord Aldington’ for his treatment of ‘people who FOUGHT AGAINST US in Italy’. The empathy mentioned above had limits, inscribed in the dust by Britannia’s trident.

If that displeases some readers, they may find solace for offended sensibilities in the writing. These letters are less mannered and more impulsive than Trevor-Roper’s. Read his outbursts of delight in Calcutta, of disgust in Whitby, of astonishment at being kissed at Eton, and you will feel you are there.

A word of warning. Tim Heald has done his best, with notes and a short index, but the names and the nicknames are not explained at each occurrence, and it is difficult to remember the true identity of Tompie, Nero,Vinegar, the Baron, the Cardinal, the Blessed Edward, the Blessed Henry and Electric Whiskers (General Vyvyan).

Apart from that, if anyone really wishes to know the sort of thing talked about in the back bar of the King’s Arms in Oxford in the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties, here it is. The public and saloon bars admitted leftists, fellow-travellers, bleeding hearts, women, and puritans.

Comments