Talk about ‘enemies of promise’.

Talk about ‘enemies of promise’. In the March 1942 number of Horizon magazine there appeared what could be a heartfelt illustration of the whinger’s conceit propagated by Horizon’s editor, Cyril Connolly, to the effect that life stifles artistic ambitions. Plate 2, ‘Dreamer in Landscape’ by John Craxton, is a pen-and-wash drawing of horny plants breathing down the neck of a dozing boy. How very Craxton. Not yet 20 and already well-versed in overgrown styling and poetic self-pity.

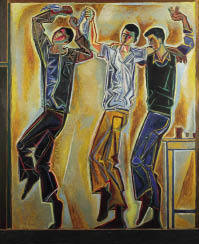

For decades Craxton lived with the fact that early promise guarantees nothing. What in his salad days denoted a growing confidence — the tidied airs, the recurrence of good-looking lads in neatly facetted littorals — became as pigeonholed as Tintin graphics. Greece brought this on; for there, post war, in the late Forties, he found his land of promise: bright, clear cut, a hedonic mosaic of favourite things with which to fill pictures. Cats, fig trees, goats, taverna enticements, islands silhouetted across twinkling seas, were slotted together on Graeco-Byzantine lines. These emblems, his surface coverings, particularly appeal to those who’ve been there, lived there, and now miss it.

In passages of text fitted into gaps between illustrations, Ian Collins emphasises Craxton’s pleasures in life. There are key occasions, such as the summer day in 1937 when he and a schoolfriend were chauffeured by the schoolfriend’s father from their Boy Scout camp on the Seine to the Paris International Exhibition where ‘Guernica’ was to be seen. ‘Picasso’s formal invention was just incredible’, Craxton said 70 years later. ‘I remember the electric light bulb very well; no one had put it in a painting before to represent the light of the sun.’ A clear outline with a squiggle filament in the middle: it was the sort of image that stayed with him throughout; that and the Picasso cat stalking the rooftops, claws gripping the tiles, torn bird in mouth. Collins brings out the scratchiness underlying Craxton’s idylls, the frequency of his being ‘low on funds’ in later years, whiling away his time on (Craxton’s word for it) ‘procraxtonation’.

Craxton died two years ago. Collins’ salute to him is an affectionate and, in places, wry contrast to the only previous monograph on the artist, published in 1948 by Horizon, in which Geoffrey Grigson extols his ‘incessant visual curiosity’, but also, cruelly, quotes him burbling away. He records him saying, for example: ‘Living today is more than an art: it’s a feat, and there are so few people one can talk to on a tightrope — let alone make love to.’ This at a time when the ‘visual curiosity’ was at its most attentive, giving rise to composites drawn from the likes of Picasso and Miro, Samuel Palmer, Graham Sutherland, Robert Colquhoun, Niko Ghika and, not least, El Greco.

For some years, until around 1948, Craxton was friends with Lucian Freud, two months his junior. They had rooms to use as studios in Abercorn Terrace, paid for by Peter Watson, the margarine heir, backer of Horizon and great patron of young artists, where they drew dead creatures and cultivated acquaintances. Of the two, Craxton was the more assured in his dealings; thanks usually to Peter Watson — and exposure in Horizon — they got to know Sutherland and others and went on jaunts to South Wales and, eventually in 1945, the Scillies, whence they hoped to be able to ship themselves to Brittany, thence to Paris and France proper. Their drawing styles and subject matter overlapped, but well before Craxton took himself off to Greece in 1946 (thanks to the good offices of Lady ‘Peter’ Norton, wife of the British ambassador) the differences were manifest. Freud joined Craxton on Poros in the autumn of 1946: same lemon trees, same sitters, but different takes entirely. Craxton resolved to settle on Crete or Hydra or Poros and become the English equivalent (‘El Anglo’?) of El Greco.

Graeco Craxton flourished, after a fashion, assimilating the light and languor of the Greek islands, doing deservedly well-received dustjackets for Patrick Leigh Fermor, particularly for those concerned with the places he knew best. He didn’t avoid London, but tended to be there for social reasons, or when Greece became too hot for him in one way and another. He and Freud diverged; you only have to look at the work to see how completely their ways parted.

One account of the end of the friendship (not given in the book) is that Craxton was miffed when, having told him that the Arts Council exhibition ‘60 Paintings for ’51’ was a silly sort of competition and that he wasn’t going to enter, Freud did put in for it after all and, what’s more, won a prize (for ‘Interior near Paddington’). Craxton, having not gone in for it himself, felt fooled. Later there were serious disputes to do with discarded and retouched drawings appearing on the market. Collins edges round these. The main thing is that Freud pressed on with ruthless singularity and Craxton did very much the opposite.

Comments