Rod Liddle says that Harriet Harman’s notion of ‘structural pay discrimination’ is nonsense. It is women’s decision to have children that disrupts wage equality

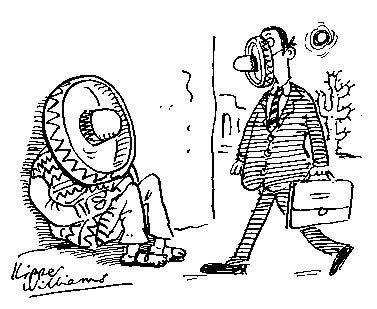

One government proposal which seems to have gone largely unnoticed as a consequence of the credit crunch, Susan Boyle’s triumph on Britain’s Got Talent and flying Mexican pigs spreading their lethal filth hither and thither is Harriet Harman’s plan to remove the wombs from all British women and force them to go to work as stockbrokers and hedge-fund managers in the City of London. How she intends to remove the wombs, and what she will do with 30 million of them when she is done, has not yet been decided. There will be ethical debates, one supposes. But in the interim it is likely that Britain will become the first European Union country with a womb-mountain. They will be stored in a deep-freeze warehouse near Kidderminster. Probably.

Harperson is absolutely determined that British women will achieve everything that British men do, regardless of whether they wish to or whether they are able to. Objections to her proposals are condemned as sexist; women do not achieve exactly the same as men right now because of structural sexism — there is no other answer.

She has been stamping her little feet around recently about differential pay rates between men and women. Men, she suggested, were paid 20 per cent more than women and that was solely down to sexism. ‘You have got to believe that either women are 20 per cent less intelligent, hard-working, less committed to their job, less experienced, less qualified — or you have got to believe that there is structural pay discrimination. We believe there is structural pay discrimination,’ she said.

Well, now. I think it is possible that Harriet is so much more fantastically stupid than the norm that this, by itself, accounts for that 20 per cent deficit across the nation as a whole which she quotes. But the bigger problem is her use of the word ‘we’ in that last sentence — because that part of the government which knows about such things, the National Statistics Office, does not believe for a moment in structural pay discrimination.

The last Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings suggested that the difference between men and women’s pay was down to the rather more straightforward point that women worked substantially fewer hours per week than men. To any normal person this seems perfectly obvious, but not to Harriet. Further, commenting upon the fact that there had been a very small rise in the gender gap for hourly pay — up to 12.8 per cent from 12.5 per cent — the NSO suggested that this was because women had moved into full-time employment, where the hourly rates of pay were lower than in the part-time jobs in which women had previously been employed.

That’s not all. In February this year, the same institution published figures which broke down the gender gap into ages, and noted that from the time men and women first start work until the age of 30, there is no differential in pay between the sexes whatsoever. Everything is exactly as Harriet would want it to be. Further, women who remained single (and usually without kids) after the age of 30 also earned just as much money as men throughout their careers — and rather more than men who remained single. Now, let me think — is there a pattern beginning to emerge here? Isn’t it the fact that women have children and consequently either give up work altogether or henceforth work part-time that is responsible for the differing pay rates between the ages of 30 and 50 (after which, incidentally, the pay differentials narrow once again)? These days, working women usually choose the age of 30, there or thereabouts, as the optimum time to have kids. Does Harriet think this is coincidence?

To any even half-sentient human being, or at least one not blinded by an outdated ideology like Harman, it is the inconvenient truth that women, being equipped with wombs, give birth to children, which results in the differences in pay, not institutional sexism. They do not work so many hours after a certain period, or they drift into less demanding jobs, or they return to the workplace quantitively less experienced than their male (and single female) colleagues, as a consequence of their central role in perpetuating the human race. And they do this because they want to do it.

Of course, the government has attempted to circumvent this inconvenience with extraordinarily generous statutory maternity allowances for women. But they had not counted on the law of unintended consequences. If you are a young couple, both in work, and have decided to have your first child, you are faced with an option: either the mother takes time off to look after the baby, or the dad does. And it isn’t really an option at all, because dad gets just two weeks off work, if he’s lucky, whereas mum gets a whole year, much of it paid, plus her old job back at the end — so in almost every case there’s scarcely a decision to be made. The government’s maternity leave allowances have made it more likely that women will leave the job market and return to it a year behind their male (and single female) colleagues in terms of experience, promotion, etc.

Not so long ago the Equality and Human Rights Commission published a report which complained that 6,000 women had ‘gone missing’ from top boardroom jobs in the City. In other words there were more men in the top positions than women. Its conclusion was un-equivocal: glass ceiling, institutional sexism, etc. The notion that the proportion of women who want top boardroom jobs was smaller than the proportion of men who wanted them did not even occur; this possibility was not even mentioned. And yet it seems to me far more likely to be the case than institutionalised discrimination against women.

Harriet isn’t really planning to remove the wombs from every British woman — although that, I suspect, is the only way she will achieve her desired result of absolute equality of outcome, rather than equality of opportunity. Instead she is making it legal for employers to discriminate on grounds of gender when appointing people to jobs. She is in favour of positive discrimination against men. I’ve never had much time for the European Court of Human Rights, but maybe it will come in useful one of these days. In the meantime, the reason women are paid less than men is precisely because, on average, they do work fewer hours, they do show less long-term commitment to the job, and they therefore are less hard-working than their male counterparts, on average.

Comments