Given the anti-Americanism displayed on every possible occasion by the French since the days of De Gaulle, and the crudely expressed contempt with which Americans have responded, particularly over the past decade, it is easy to forget that the two nations once enjoyed a relationship even more ‘special’ than the supposedly exclusive one between Britain and the United States.

That relationship, which began with Benjamin Franklin’s seduction of French society and Lafayette’s participation in the American revolution, blossomed into a love affair in the two decades following the Great War. Many Americans who had fought in it stayed behind. The comparatively low cost of living permitted penniless writers and artists, as well as society ladies, to congregate in Paris. The absence of prejudice against African Americans induced musicians and entertainers, such as Josephine Baker, to settle there. And with the outbreak of civil war in Spain, Paris became the point of entry and exit for American volunteers.

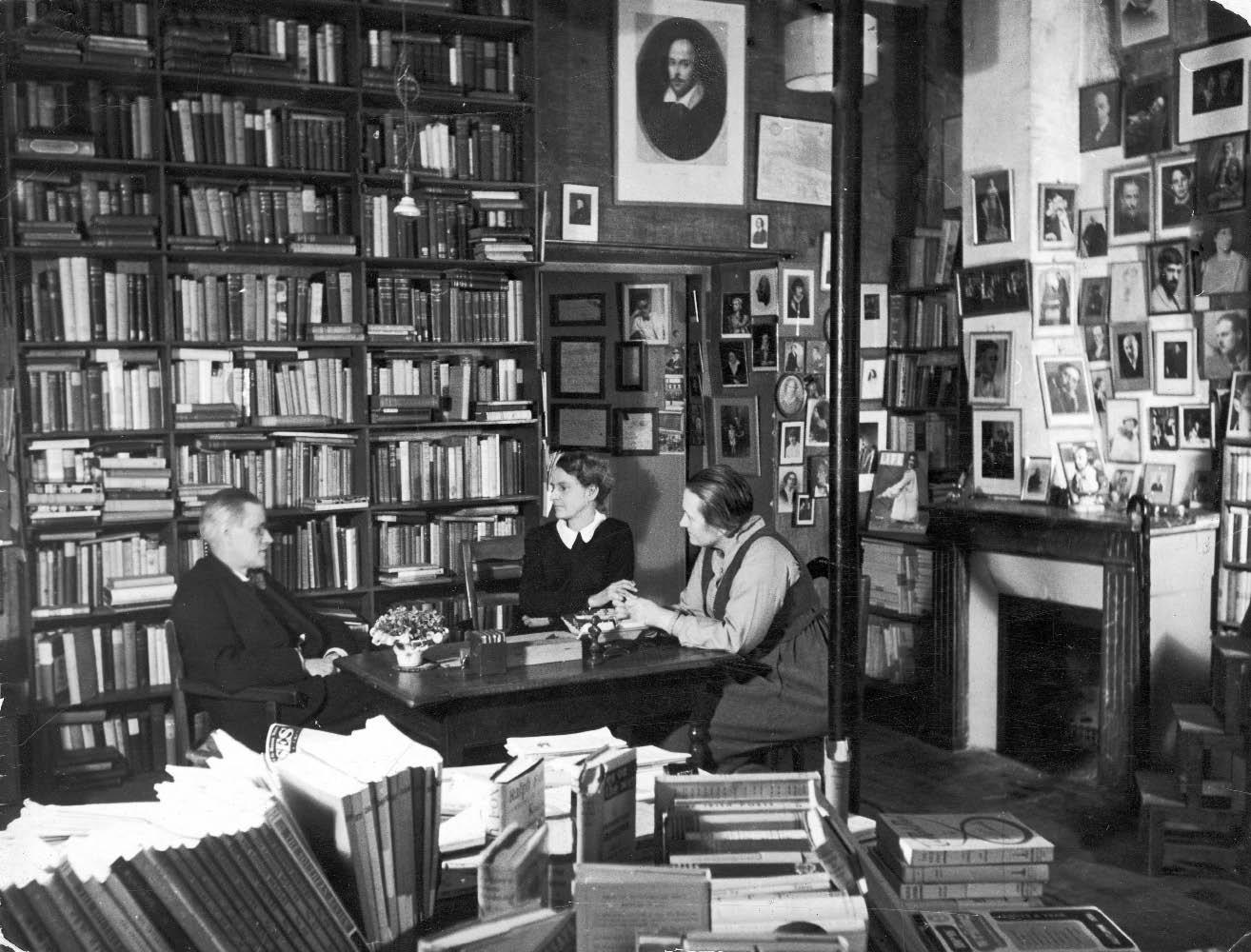

It was on the left bank, ‘Stratford-on-Odéon’, as James Joyce called it, that the relationship blossomed most spectacularly. The bookshop and lending library Shakespeare & Company was opened by Sylvia Beach on the rue de l’Odéon in 1920. It was frequented by Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ezra Pound and Henry Miller, as well as Joyce (whose Ulysses Beach first published), T. S. Eliot and W. H. Auden, to mention but the best-known, and brought them into contact with France’s greatest, from Valéry to Gide.

At the outbreak of war in 1939, many of the 30,000 or so Americans living in France gave active or moral support to the French cause. Most of them left when that collapsed in June 1940. But Ambassador William C. Bullitt remained at his post (helping to save Paris from a damaging battle), and some 5,000 took advantage of America’s neutrality to stay on under German occupation.

By the time the United States entered the war at the end of 1941, there were only about 2,000 left, and while a number were interned, they were treated far better than other enemy aliens. Shakespeare & Company was forced to close, but the American hospital continued to function, under the chairmanship of the American-born Count Aldebert de Chambrun, a direct descendant of Lafayette, as did the American library, under the aegis of his wife, who was closely related to President Roosevelt.

With time, the miasma of war began to infect even the Americans; some drifted into various forms of collaboration, others into resistance. All paid a price. The hospital’s director, Dr Sumner Jackson, treated escaping allied airmen and directed an intelligence-gathering network for the Allies, which cost him his life. His superior, who, along with his formidable wife had for decades been the very embodiment of Franco-American friendship and political solidarity, was persecuted by self-appointed resistance leaders and cold-shouldered by the new France. Their son René, who had shown exemplary patriotism in 1940 but happened to be married to the daughter of Pierre Laval, had to go into hiding. And although Hemingway turned up gun in hand in 1944 to ‘liberate’ it, Shakespeare & Company never reopened. The special relationship withered.

Charles Glass handles this rich and complex material well, and while the book could have been shorter, he never loses the reader’s attention. There are solecisms, some unfortunate, like the no doubt typographical confusion over the date of the 20 July plot, others surprising, like his use of the word Kulturkampf (Bismarck’s anti-Catholic campaign in the 1870s) to denote Germanic attitudes to culture. He follows the now widespread practice of awarding De Gaulle a small ‘d’ yet betrays a lack of familiarity with the particule nobiliaire, which is only used in conjunction with a title or a first name: ‘de Chambrun’ on its own sounds as silly as would ‘of Wellington’.

The story Glass has chosen to tell may not be central to it, but involving as it does a wide spectrum of humanity caught up in the conditions of wartime France — a cocktail-party by comparison with the danse macabre taking place elsewhere in Nazi-occupied Europe but one haunted by suffering and tragedy nonetheless — it provides valuable insights into a little-known theatre of that great tragi-comic mess which we call the second world war.

Comments