Who reads Ralph Hodgson’s poetry today? Probably few people under the age of 40 have even heard of this strange Englishman who died in 1961 in a small town in the American mid-west. His most famous poems are those once learnt by schoolchildren like ‘Time you old Gypsy Man’ or ‘The Bells of Heaven’, both little more than pleasant rhymes.

But in his day Hodgson was admired by (among others) Robert Lowell, Siegfried Sassoon, Stephen Spender and T. S. Eliot, who wanted him to illustrate the book that he had partly inspired — Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats; the lazy Hodgson could have made a fortune from the project but refused.

In fact he mostly did exactly what he wanted, in his life and his work. Living to be over 90, through immense changes in literary fashion, Hodgson wrote an unchanging poetry of the heart, prompted often by animals or landscape, simply expressed, yet preoccupied with fantasy and myth.

For Hodgson, writing’s inspiration could not be defined; he abominated literary theory. His pantheistic approach often prompted an ecstatic outpouring, as in the extraordinary ‘The Song of Honour’, a joyful vision of a magnificently varied world. Yet, although not at all intellectual, he can be extraordinarily obscure. For instance, in ‘The Muse and the Mastiff’, a dog dreams of a bear whose story is told by a muse to a poet who tells the story again to the owner of the dog. Got it?

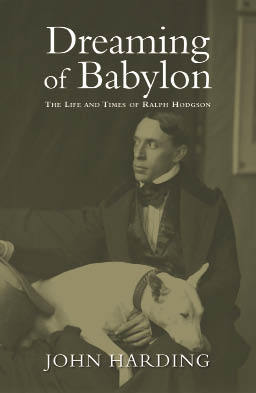

His quest for the wild and the mysterious began early. From a working-class background in north-east England, Hodgson had little education and was roaming with fairground people and gypsies from the age of 15. A talented illustrator, he came to London and worked for popular magazines, but poetry was his true calling. Indolence held him back, as did his eccentric personality that soon got as much attention as his work. An aficionado of bull terriers and boxing, claiming to be happiest among gypsies and fellow dog-fanciers, he could talk compellingly, often while lying down to relieve agonising piles, a result of bird-watching in damp fields. He disliked literary conversation and had a tendency to shout, in his talk and his verse.

If he belonged anywhere, Hodgson was a Georgian, the pre-1914 school of poets later eclipsed by the modernist revolution of Pound and Eliot. Georgian poetry was often pastoral yet the best had also a new, earthier language and subject matter: a break with late Victorian formality or fin-de-siècle decadence. Although Hodgson persistently used ‘thee’ and ‘thou’, his style is bright and vigorous, never limp. He yearned strongly for a pre-industrial world of free people and wild animals, for torrents of birdsong in lost, overgrown meadows or deep forests.

After the first world war (in which he served on the home front) Hodgson taught at Sendai University in Japan, his first wife’s painful death having prompted one of his few poems of intimate sympathy, the haunting ‘Silver Wedding’. He had no children but married three times. His second wife left, loathing Japan; the third, a much younger American, looked after him devotedly until his death.

Although a declared patriot, Hodgson preferred to dream of England rather than to live there. He came back to London in 1938, detested the political and literary gloom and left for a remote village in Ohio. Although his admirers increasingly cherished his eccentricities as much as his writing, he was admired enough, aged 82, to get the Queen’s Medal for Poetry and to be helped financially by rich well-wishers.

Ralph Hodgson needs to be rediscovered. The difficulty for a biographer is that, behind the noise, he kept his life to himself; perhaps indolence or his puritanism — he did not drink and was anti-blood-sports — prevented self-revelation. Yet John Harding has set out delightfully what there is to know about this strange figure, catching his fresh innocence and truculent, mesmeric voice. Above all he has done what Hodgson would most have wanted: sent the reader back to the poetry.

Comments