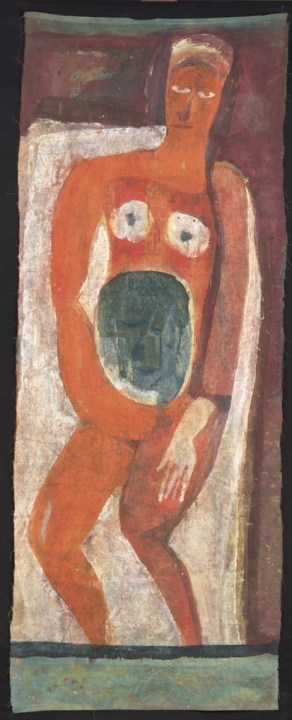

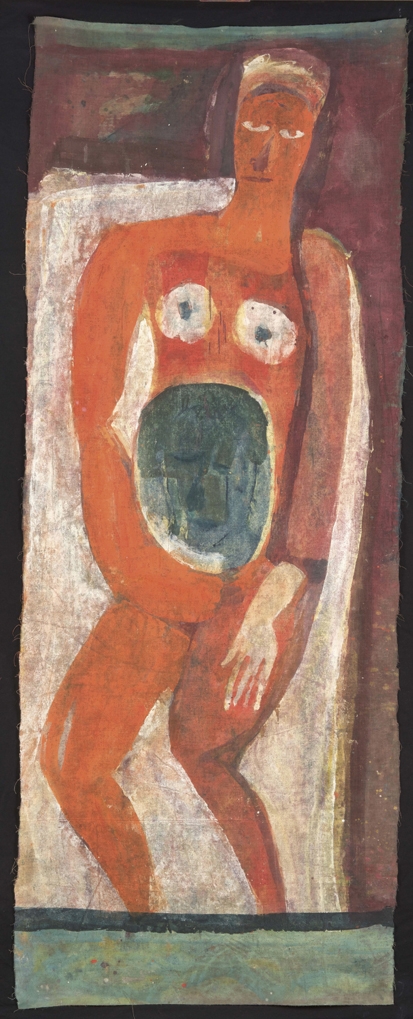

Mark Shields is a painter of considerable versatility and skill who is unable to rest on his laurels. Born in 1963 in Northern Ireland, where he still lives, he developed a powerful realist style that owes much to the Old Masters, and scored early success with meticulous portraits and still-life paintings. If he had been happy to continue in that vein, he would no doubt have made a very good, if safe, living, but ambition and self-questioning have led him on to develop new ways of painting and drawing, from mysterious, atmospheric landscapes and complex narrative pictures to large-scale pastel drawings on canvas. Shields speaks of a dread of falling into rhythms of working that lead inexorably to unthinking habit, and continually experiments with materials in an effort to insure against this. His latest work signals yet another departure: a series of 99 paintings of mostly single figures in oil on muslin, each measuring some 5ft by 2ft. The figures are primitive and telluric, recalling painted linen shrouds from Egypt, medieval wall paintings, Byzantine altar cloths, Fayum mummy portraits and many other unexpected sources. This stupendous collection of images — raw, emotive, enlivening, disquieting — is currently on show at two London galleries (until 7 March) that are only a short walk apart: Grosvenor Gallery, 21 Ryder Street, SW1, and Browse & Darby, 19 Cork Street, W1.

The two exhibitions are hung similarly, over three floors in each gallery. The paintings are divided in alternate quartets, with the first four at Browse & Darby, the following two pairs at the Grosvenor, and so on, more or less faithfully, though there are 55 in total at Grosvenor and 44 at B&D. Painted as pairs (except for the very last one), they suggest their own groupings. The idea of finishing the sequence on an odd number was to leave it open-ended, what Shields calls ‘a perpetual incompleteness’. He tried out various descriptions of his figures: ‘There was almost an army of them; a community; a congregation; then Host came to mind. The idea of the 99 has a connection with the parable of the lost sheep — which suggests that the one that isn’t there is the important one. That’s what so many of us are engaged in — striving after the unattainable.

‘Initially I hadn’t thought they would be paired, that came about because the muslin is so thin. I was working on it on the floor and the paint was going through and soaking into the paper underneath. So I put down two layers of muslin and got an almost identical image on both, then kept working on them in different ways: a layering process with accidental things happening — bleeding and staining. I forced myself to try to do four figures in a week — two pairs. It was important not to get bogged down — the material doesn’t allow for it, it starts to clog up with paint. Even though the oil is very dilute, it has some plaster in it to keep it matt, and the danger is that it fills the weave too quickly.’ Shields is concerned to keep that stained quality — the paint in the fabric, passing through as it were, rather than resting on top of it — which reinforces the spontaneous feel of his imagery.

Usually, as preparation for paintings, he makes a lot of drawings in ink or charcoal on paper, but for these figures there were no preliminary studies. They are painted direct, straight in, often without any reference to work from. He says: ‘I had no plans at all: I couldn’t say what I’d do next week or what no. 40 would be. They grew out of each other and what was happening that week. I think of them as a Book of Hours, as if they’re markers — time markers but activity markers as well.’ To a certain extent these images reflect events in his life, things that affected him — hearing of a tragic death, reading a particular poem, going to a wedding — moments that were enough to spark off or unleash an image. Gravediggers, ballerinas, angels, holy fools, poets and worshippers, characters from classical myth or the Bible, primordial energies — all these meet and mingle in Shields’s dramatis personae. He is less interested in appearance than in essence — the mystery of the inner life. These are universal, hieratic images, non-naturalistic representations of types (states of mind, conditions of soul), conveying a larger truth than the specifics of personality. The awkwardnesses, the primitive simplifications, are strategies to sharpen the eye and defuse sentimentality.

Frayed edges are visible, and the bowed top of the muslin sheet, emphasising the physical reality of the painting. In fact, Shields sees them more as objects than paintings. ‘At last I wasn’t worried about making pictures — paintings stretched on canvas. These seemed much more like Tantric prayer hangings, votive banners.’ He likes the idea that they may be discovered hundreds of years hence rolled up in a box and the question will be ‘I wonder what these were used for? Some sort of initiation rite?’ Shields subverts our expectations of what paintings should look like.

‘I’m finding that an awful lot of things are pointing back to childhood. And maybe that’s slightly to do with the worry about making genuine statements. You can be so involved with looking at art of the past, and all the things that influence you, that you don’t know what’s you any more. So maybe your childhood is the most genuine of all. What are the things that interested me then? I liked stamps and maps and I think that’s significant. Stamps are the world in miniature, and they’re beautiful things in themselves. I copied maps endlessly as a child. They’re all about shape: an outline and a symbol. South America was a favourite. Then there are the biblical references, more obvious here than in any of my previous shows. That’s a childhood thing, too — Bible illustrations. Gloomy steel engravings but which had a glow which made you think of a mysterious world, and the more crude woodcuts in other books, prophets awkwardly standing by the shore. All of those things are starting to feed in to the work.’

Ultimately, the identity of Host is a double one: composed of paired images, presented in two galleries, illuminating the age-old opposites of human nature, essentially about good and evil. Shields is a man of religious belief, but he also thinks that what helps produce work (for him) is questioning how strong that belief is. ‘With two versions of the same idea, sometimes there’s an earthly one and a more idealised or spiritual one. There’s a passage in Kafka’s The Castle when somebody asks why use two words when one would do. The answer is something like: because the truth always dwells in the other. And that’s partly this as well: having a second voice that contradicts, and maybe that’s the real voice.’ In the end, though, either the picture works or it doesn’t — it doesn’t need a huge weight of verbal justification behind it. The proof is in the looking, and these remarkable paintings amply repay close attention.

Comments