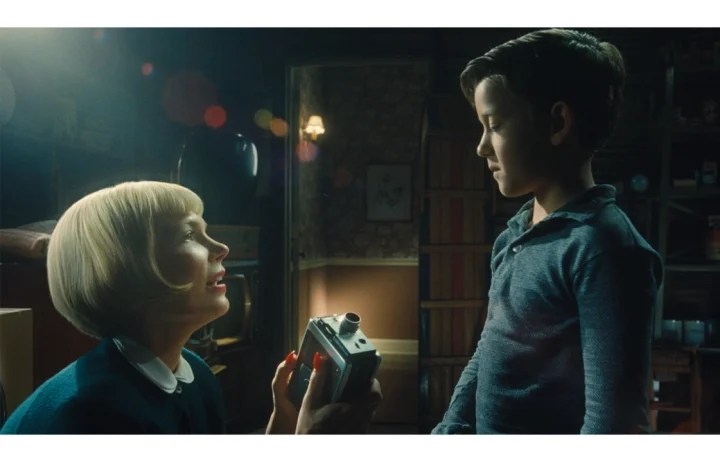

Steven Spielberg has suggested that The Fabelmans, his latest film, is a $40 million therapy project. The Fabelmans focuses on divorce and in doing so holds a mirror to the director’s own parents’ split.

In its unblinking depiction of what has for so many become a rite of passage – almost one in two marriages end in divorce — the film makes for uncomfortable viewing. Spielberg refuses to indulge those parents who depict marital breakdown as just another milestone in a child’s life. He portrays it as a tragedy that casts a long shadow.

‘Everything in his career is marked by his parents’ divorce,’ one critic concluded. This is true of many of us who have experienced divorce. I was 13 when my parents divorced. Their lawyers marvelled at how civilised the break-up was, yet it has marked my life ever since.

We can follow Spielberg’s example and speak honestly about family breakdown

As a teenager, I needed more friends, and more from friendships, in order to counter the insecurity fostered by the crumbling of 13 years of certainties: that my parents loved each other, that they would always be together, that we were a happy family.

My inability to maintain a happy relationship in my 20s was only to be expected, a therapist warned me: I was like a child being asked to build a castle out of Lego pieces when they have no idea what a castle looks like. His verdict was spot on – but the sessions did little to improve my disastrous attempts at emotional architecture.

My parents’ divorce did fuel professional ambitions. If I couldn’t rely on the stable launchpad provided by a happy family, I knew I must work harder to make up for my disadvantage. I buried myself in journalism, turning colleagues into family and newsrooms into homes.

There were very practical consequences, too: my brother and I shuttled from Washington DC (where my father stayed) to London (where the rest of us were based) for the holidays, trying to divide our time equally between two households. Later, when our parents became frail and infirm, their transatlantic separation raised new worries: what would happen if they were simultaneously in critical need of our care and attention? We ended up moving them both back to my father’s native Italy. They lived in adjoining apartments – still unable to cohabit (‘she is impossible!’; ‘he hasn’t improved with age!’), but at least in one location, so that my brother and I only had to undertake one round trip rather than two.

It is perhaps unsurprising that when I finally married (at 43), my husband was in the midst of a divorce. Edward and I seemed to have little in common, apart from not owning a television, and loving long country walks. But we shared a determination to build a strong and loving marriage, till death us do part: we had both suffered the trauma of family break-up.

As have many others. Divorce may no longer carry the stigma of the 1960s, when the Spielbergs’ and my own parents’ marriage broke down, but it still carries consequences. Trouble at school, trouble with the police, substance misuse, debt and homelessness: family breakdown increases the risk of them all.

Unlike Spielberg I cannot point to brilliant box office hits influenced by my parents’ break-up. But I can say that what I do now is linked to having grown up in the shadow of divorce.

Some promising initiatives have surfaced. Reducing Parental Conflict is a government-funded and evidence-based programme that intervenes early in parents’ relationship to stop the rows escalating. Family hubs, which deliver services to support families affected by debt, drink, isolation — some of the triggers for divorce – are mushrooming across the country. Meanwhile some schools now take steps to help children who are reeling from their parents’ break up.

The government has appointed a new cross-government advisory group on family policy to ensure any new strategy will promote families – and I am honoured to be a member of the group. It was also encouraging to hear the PM speak about the importance of families earlier this month — but why not say that one type of family, marriage, is best for children?

The British political class seems more interested in nannying than in promoting stable, two parent families. Yet surely a government that issues warnings about cakes in the office and switching on kettles at home can also stress the importance of marriage? Politicians are nervous of being seen as judgemental by voters, many of whom have experienced marital failures and don’t like being talked down to.

But surely we can celebrate the heroism of lone parents who raise children in a loving home without pretending that theirs is the model everyone should aspire to. Even small changes can encourage couples to wed and stay wed, such as allowing married couples to share 100 per cent of personal tax allowance income.

The recent Children’s Commissioner Family Review found one in two children are born outside of marriage.

Recent research shows that married parents are twice as likely to stay together as cohabiting ones. By the time they turn five, 53 per cent of children of cohabiting parents will have experienced their parents’ separation; among five-year-olds with married parents, this is 15 per cent.

The difference in educational outcomes and wellbeing between children born in marriage and those born of cohabitation is also significant. According to pre-pandemic ONS data, 6 per cent of children aged 5 to 10 years old who have married parents are diagnosed with a mental disorder; but among 5 to 10 year olds whose parents cohabit that percentage doubles.

Even a small tweak in government policy in favour of marriage could create an important transformation. We can’t all be Steven Spielbergs, mining our troubles for Oscar gold. But we can follow his example and speak honestly about family breakdown and, in doing so, urge our politicians to do what they can to help.

Comments