Cold War Prague hid its historic charms under a veil of grime and dilapidation. But, as we learn from this deeply researched and scholarly study, it was still a favoured destination for international terrorists, mostly Palestinians, after the 1968 Soviet invasion. They liked its hotels, its proximity to the West, its medical facilities, the tolerance and support of its security authorities and the quality of its light-arms manufacturing.

Communist Czechoslovakia (CSSR) boasted relatively efficient security and intelligence services (generically referred to as the Stb). They were scrupulous record- keepers, and Stb archives, released after the Velvet Revolution with minimal expurgation, remain among the most complete of any former Warsaw Pact nation. Daniela Richterova, a senior lecturer at King’s College, London, has become their preeminent interpreter and historian.

Western intelligence personnel who lived and worked behind the Iron Curtain were there to conduct the espionage dimension of the Cold War, as I did myself. Palestinian terrorism was a secondary concern. We were of course aware that Palestinian terrorists enjoyed sanctuary in central and eastern Europe, but we lacked precise knowledge about it. The question of what support they were actually being given by the intelligence and security organisation of the Warsaw Pact remained vague and speculative. Now, half a century later, we are presented with a detailed picture of what was going on in Czechoslovakia. For former professionals and historians alike, it is a fascinating exposé.

Richterova has immersed herself in the Kafkaesque Stb archives for a decade and has definitively filled the gap in our understanding of this hidden dimension of the Cold War. Watching the Jackals documents in detail four Stb relationships: with Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO); with Wadi Haddad and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP); with Carlos ‘the Jackal’; and with Abu Nidal (ANO).

Arafat was, of course, an acknowledged official visitor to the CSSR and was treated as a diplomatic VIP; but there was an important clandestine component to the relationship. The foreign intelligence directorate of the Stb were keen to ride on the back of the PLO’s Middle Eastern network of security contacts and sources. But, despite the Stb’s best efforts, the PLO security officials usually seemed to fall short of Czechoslovak expectations. The Stb were still generous in the provision of extensive training to PLO operatives; their investment in the relationship was substantial, but the returns to the CSSR were meagre. The PLO did very well out of it.

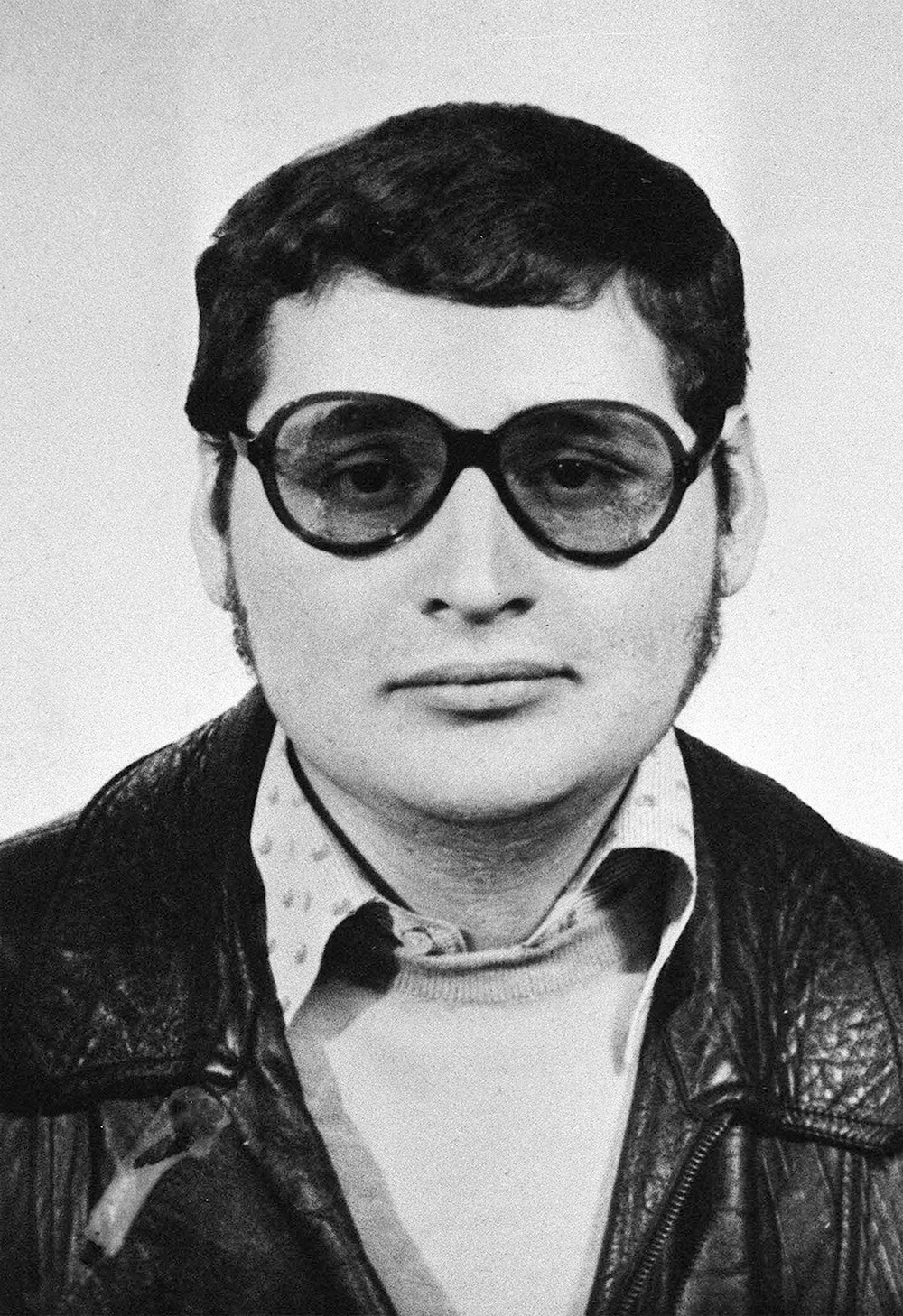

The three other relationships were markedly different. The terrorism that these dangerous individuals and their followers committed was to the forefront: they were violent and unpredictable. What is striking is the ease with which these notorious terrorists moved around the Soviet bloc, using genuine Middle Eastern diplomatic passports in various identities. Little effort was made to hinder them, but, as the risk of their presence in the East becoming known in the West began to escalate, so the support of Stb officers mutated into an exercise in control. The hot-tempered Carlos was a particular liability – for example, waving a pistol around in the public areas of the Intercontinental hotel in Prague when he felt the service was not up to scratch. This was also the era of detente, when the Reagan administration was pressing the Soviet bloc to expel terrorists they were harbouring.

What Richterova has revealed is the sophisticated risk management that the Czechoslovaks themselves developed to deal with the reputational and political risk to the CSSR. Stb officers, together with the international department of the Communist party, confidently created their own initiatives without reference to Moscow, keeping their KGB overseers informed after the event. In using the term ‘Soviet bloc’ we imply the existence of an autocratic monoculture, especially in the intelligence and security sphere. But what Richterova describes is more subtle and multilayered. In one instance we see Omnipol, the Czechoslovak arms agency, refusing to supply pistol silencers to the PFLP on the grounds that they would be used to carry out assassinations. The CSSR, over time, was becoming more aware of the risk it was running to its international reputation; and, as it did so, former guests translated into unwanted visitors.

Carlos’s arrogance and notoriety led him to overplay his hand and he was banned from Czechoslovakia. Of the terrorists described, he is the one who remains alive – in a French prison, where he will live out his days. In 1975, in Paris, he murdered two French security service officers and their informant, and thus became France’s most wanted criminal. French intelligence eventually caught up with him in Sudan in 1994. He had run out of places to hide.

Perhaps the most surprising revelation in Richterova’s book concerns a successful Stb operation to penetrate the ANO, the most dangerous terrorist group of that period – a formidable intelligence achievement of which any of the West’s major services would have been envious. That level of sophistication shows the value of the best Stb’s operations, their importance to Moscow and their relative independence of action. The same service had impressively managed to recruit several British MPs in the 1960s (about whom Richterova has also written).

The life of Abu Nidal, aka Sabri al-Banna, ended in a Baghdad apartment in 2002 after he, too, had run out of luxury holiday spots for R&R – though as late as 1991 he was relaxing at a Swiss mountain resort using a Libyan diplomatic identity. The story is that he committed suicide after he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Others allege that he was found dead with two gunshot wounds to the head.

What is striking about Richterova’s study is how easily and uncritically Czechoslovakia fell into support for terrorists, for no political reason other than to oppose and aggravate the West. However, de-risking these relationships and disentangling the country from them as they grew in liability also absorbed significant intelligence and security resources. There is a general lesson here: that state support for terrorism almost never delivers positive outcomes. The Stb, leaving aside the ideological divide that defined the Cold War, had to discover this for themselves. Their journey down that road is now revealed and described for the first time – and, more importantly, has been fully documented for the historical record.

Comments