The Starland Vocal Band were on to something. In their 1976 hit ‘Afternoon Delight’ they sang, in gruesomely twee harmony: ‘Gonna grab some afternoon delight/ My motto’s always been when it’s right it’s right/ Why wait until the middle of a cold, dark night?’ Granted, they were singing about rumpy-pumpy, not theatre-going, but for many of us the same principle applies.

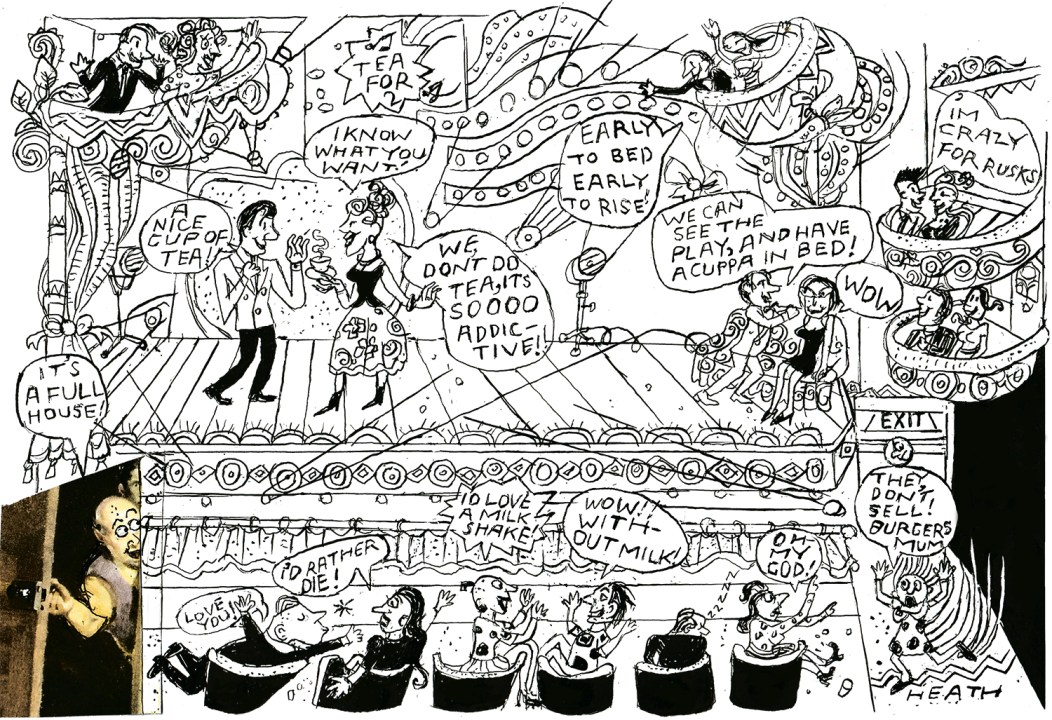

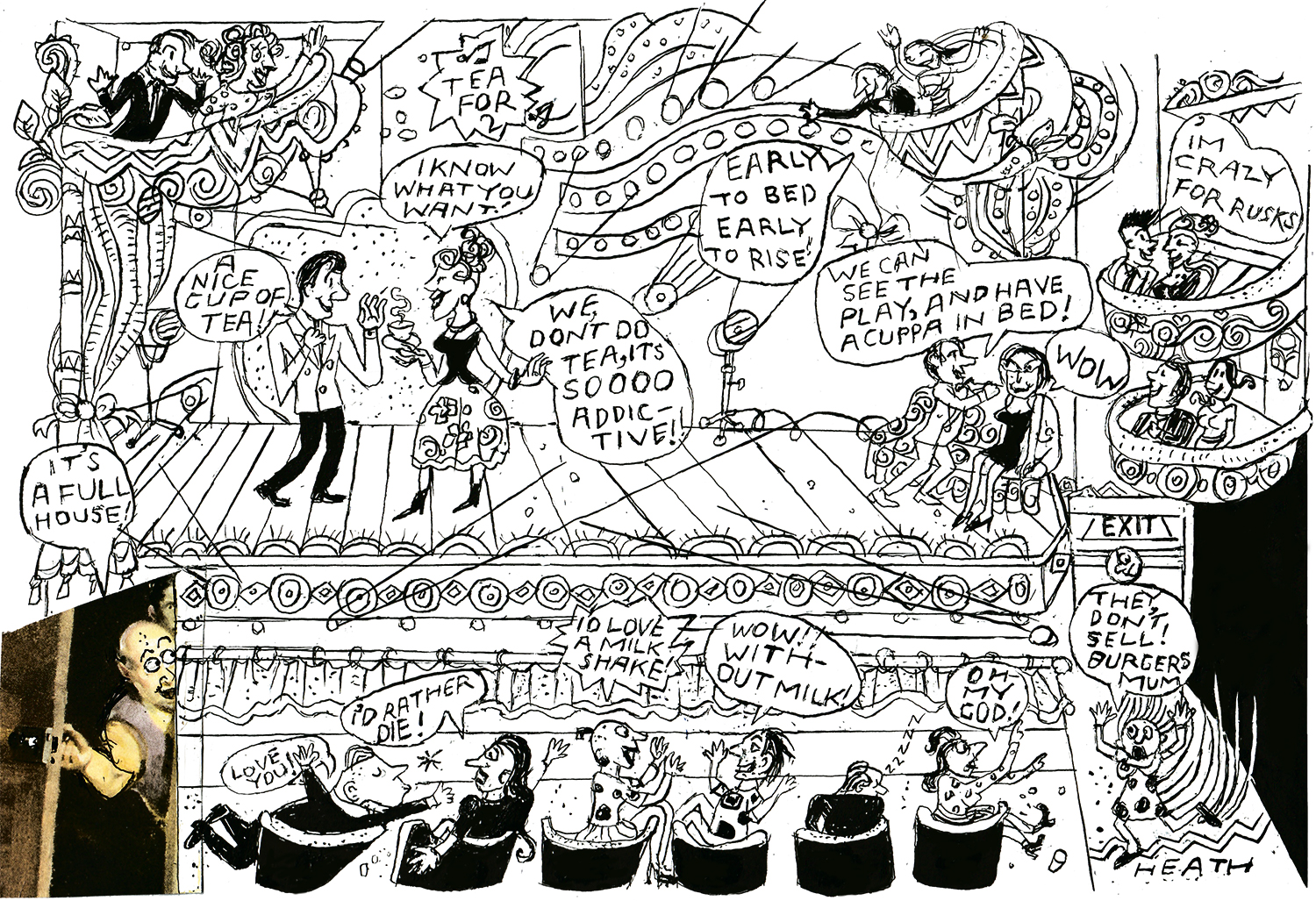

‘I’ve turned into the kind of person who loves toddling off to matinees,’ admitted my actor friend Timmy recently. He’s not the only one. I’m at that age when lunch is preferable to dinner and matinees appeal far more than evening shows. There’s something hedonistic about a matinee. When everyone else is working (or should be), you’re luxuriating in the theatre. And if the production is a dud, it’s far less stressful.

My wife and I once saw an evening performance of Long Day’s Journey Into Night which turned out to be just that. After our theatrical punishment beating we began the freezing assault course of our journey home. Having dodged pools of vomit and jostled our way into a dirty Tube carriage crammed with baying drunks we got home in the early hours, depressed, angry and exhausted. A matinee would have allowed for a consolatory post-mortem over a glass of wine and we would have had the rest of the day to enjoy: the chance to clutch evening victory from the jaws of afternoon defeat.

The rising popularity of matinee idling partly explains why theatre audiences have held up so well. Ticket sales are now back to pre-pandemic levels and, in some cases, afternoon shows are outstripping their evening counterparts. Matthew Byam-Shaw, co-owner of Playful, one of Britain’s largest independent production companies, says some of his daytime audiences have risen 20 per cent in the past couple of years. And they are ‘much less octogenarian than they used to be. Because whatever age you are, you tend to feel happier, and safer, at a matinee.’

There are also now far more opportunities for a matinee idyll. Nica Burns of Nimax, which owns six West End theatres, puts it down to changing lifestyles: ‘It’s much easier to pop out to a matinee when you’re working from home or have a portfolio of jobs,’ she says. ‘And people love the fact that they can avoid the rush hour and still see something remarkable.’

Ironically, the pandemic – which many thought would be the beginning of the end for live performance – has been a blessing for some. Wigmore Hall, the renowned classical-music venue, now stages twice as many daytime concerts as it did before Covid struck. Cannily, director John Gilhooly used those awful 18 months to fix the roof while the sun wasn’t shining.

‘We did lots of concerts online for free, got 15 million views in total, and found a new audience. A lot of them were younger and more international and (once lockdown ended) lots of them started coming to matinees. It created a new hunger for live performance. Once they’d seen us online, they realised what they’d been missing.’

There’s something hedonistic about a matinee

Cinema attendance, on the other hand, has crashed by a third since Covid. It’s partly the Netflix effect, of course. And perhaps, the fact that a film has no creative evolution: it’s the same product every time.

The matinee-ification of live performance won’t stop. An increasing number of smaller theatres now schedule evening shows earlier in the day at 5 or 6 p.m. The bigger houses might soon follow suit. ‘We’ve done this before and would definitely do it again,’ says Nica Burns. ‘We always like to consider what our audiences want.’

One thing audiences want, of course, is affordable tickets, and matinees also deliver on this front: two plum seats for Hamilton cost around £250 in the afternoon, but north of £400 later on.

Historically, matinees were once the only game in town. When the British theatre boom started in the late 1500s most shows were performed in daylight as cities were too dangerous at night. Artificial lighting – whether elaborate candle-stuffed chandeliers or, much later, gas lighting – was considered too expensive and a fire risk. Electricity paved the way for the evening slot, and by the 1920s matinees had become more the exception than the rule.

There is a flip side to a matinee idyll: the perception that actors don’t give their all because afternoon shows don’t really matter. The film star Luke Evans, who has occasionally trod the boards, once suggested that people should avoid matinees for this reason.

‘The age profile of some matinee audiences means there may be a bit less snap, crackle and pop in the space and that can affect the performance,’ admits veteran stage actor Michael Simkins. ‘But the only matinees I’ve known sag are ones where you’re near the end of a ten-month run and the cast are a bit bored, so energy levels drop. In that case matinees get affected. But that’s not a matinee thing, that’s a long-run thing.’

Matinees can provide more than 30 per cent of total income: the difference between life and death

There was a time when the Luke Evans view held sway among Hollywood types, and stars – as in real life – tended to come out only at night. A showbiz mole tells me that until recently, some would simply refuse to do matinees, so producers had to take the hit and hope evening takings would make up for the holes in their schedule: ‘But then producers started playing hardball. And most stars, bless them, fell into line. But what actor wouldn’t fancy performing to a packed, adoring house, even if it is 2.30 p.m.?’ This explains why, in the past 12 months alone, Adrian Brody, Sigourney Weaver, John Lithgow and Sarah Snook have all done full West End shifts.

For some, the matinee habit is so ingrained they won’t even consider evening shows. Jez Bond, artistic director of the much-garlanded Park Theatre, says many of his regulars are die-hard matinee-only types. ‘We’ve just staged One Day When We Were Young, about a 1940s war romance, and matinees were rammed,’ he says. ‘The evening shows were OK but the afternoons made the difference.’

Matinees, in other words, are not just a pleasant way to avoid the horrors of the real world for two hours. For some theatres they provide more than 30 per cent of total income: for a business, the difference between life and death.

They also reduce the risk of people like Timmy and me emulating Sheridan Morley, the late theatre critic given to snoozing (and occasionally snoring) through many a play. As the Starland Vocal Band so eloquently put it, things are ‘a little clearer in the light of day’, when you ‘know the night is going to be here anyway’.

Jonathan Maitland and Nica Burns, co-owner of six West End theatres, joins the latest Spectator Edition podcast to discuss the revival of the matinee:

Wilko: Love and Death and Rock’n’Roll, by Jonathan Maitland, is at the Southwark Playhouse Borough until 19 April. A small number of matinee seats are still available.

Comments