Katy Balls has narrated this article for you to listen to.

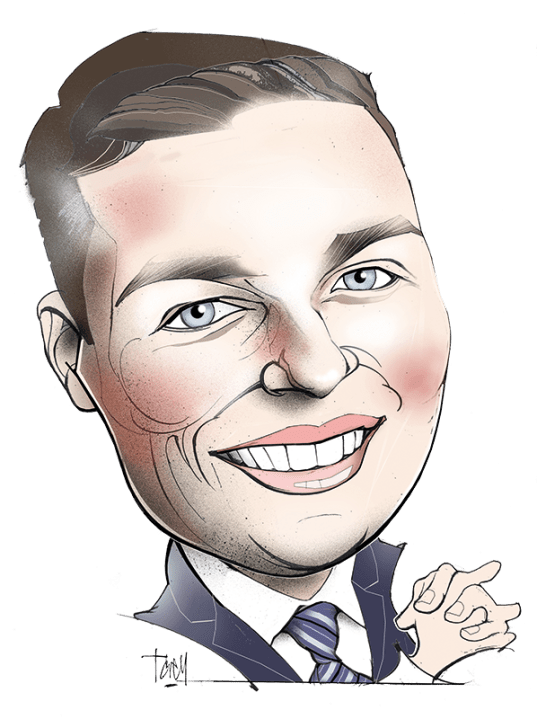

A copy of a leading article from The Spectator is stuck to the wall of Wes Streeting’s office in the Department of Health. ‘Is Wes Streeting the Hamlet of the Health Service?’ we asked in October, warning against the perils of inaction. ‘We were so riled by it we stuck it there to hold ourselves to account,’ Streeting explains. ‘We’re going further than your prescription, though. We thought it was insufficiently radical.’

The Health Secretary has certainly been busy. Over the past few months, he has unveiled a range of reforms, including abolishing NHS England. His Blairite zeal annoys some in Labour. He languishes in 21st place in LabourList’s cabinet league table of party members’ favourites. The party’s grassroots won’t be reassured by the new admirers won over by his bureaucracy-bashing. ‘Lots of my Conservative predecessors and special advisers said, “We really should have done this”,’ he says.

‘We knew we had a mountain to climb… we’ve left base camp but there’s still a long, long way to go’

On the day we visit his office, Streeting is celebrating. ‘You have arrived on an auspicious day,’ he declares. ‘Because the latest figures show that NHS waiting lists have now fallen six months in a row; that we promised to deliver two million more appointments in the first year of a Labour government [and it’s] a milestone we hit seven months early.’

This progress, however, is still far slower than the independent Institute for Fiscal Studies forecast says is necessary. And Streeting knows there is much more to do. ‘I feel confident about the direction of travel we’re on, but not complacent,’ he says. ‘We knew that we had a big mountain to climb when we came into government. We’ve left base camp behind but there is still a long, long way to go.’ His goal is to reform a health service that his own adviser Paul Corrigan has warned could collapse because of an ageing and sicker population. Does Streeting agree? ‘“A tidal wave of doom”, as Paul Corrigan might say. And I always listen to what Paul says.’

Corrigan is an ‘adviser at large’, one in a line-up of veterans from the Tony Blair years, including former health secretary Alan Milburn. They are shaping an agenda which gives NHS professionals greater autonomy while also holding them to account.

Streeting downplays the roles of the Blair old guard to an extent – ‘[Corrigan] regularly just strolls into the office, offloads some wisdom, waves, and then leaves again’ – but he is animated by the idea of an NHS which is more responsive and entrepreneurial. ‘We have got actually on our doorstep in Pimlico teams of community health workers who are going door to door in areas with high levels of deprivation and high need and proactively identifying people whose needs are not being met,’ he says. ‘Their interventions are reducing A&E admissions by about 7 per cent in that case, which is not inconsiderable when you’ve got some of the local A&Es full to bursting. That’s bottom-up initiative.

‘It’s one of the things that’s driving my conviction that at the heart of Labour’s reform agenda for the NHS has got to be the biggest devolution of power in the history of the NHS. We have got to get away from the idea that a system this large, this complex, this diverse, can be commanded and controlled by one person sat in this office in Whitehall or indeed the chief executive of the NHS or the permanent secretary for the department.’

There is a contrast between Streeting’s desire to devolve and the approach at the Department for Education, where his colleague Bridget Phillipson wants to restrict frontline autonomy, even to the extent of dictating school uniform policies.

‘What I care about is ends not means,’ he says – another Blairite echo. ‘I want to give people the freedom to design and deliver their services and I’ll hold them to account on the ends, the outcomes. The other big plank of my reform agenda and where I’d argue we’re going to a more radical place than even your exhortation in your editorial in The Spectator is on patient power, and making sure that people from working-class backgrounds like mine have the same choice and the same control, the same freedom to choose their healthcare, as someone from the wealthiest background.’

This vision of individual control of state provision is in the tradition of Blair gurus such as Julian Le Grand, but Streeting is careful to stress his respect for all of Labour’s wings. He cites Andy Burnham as a helpful voice: ‘The great thing about Andy is that he’s at the other end of the telescope now. He’s been in this role, he’s led nationally, but in terms of the devolution agenda and where we want to go, he’s doing some really interesting things in Greater Manchester.’

What does he make of Burnham’s less helpful interventions? The Greater Manchester mayor has often been critical of Keir Starmer’s government, most recently attacking the Chancellor’s welfare cuts, declaring: ‘If I was in parliament now, I would be saying “I’m not happy, you need to change this”.’ Streeting pauses before he replies: ‘I have lots of respect for Andy and I think we need critical friends but he’s a friend more than he’s critical and that’s the general message I’ve taken.’

Despite Labour’s bumpy start in government, Streeting is optimistic about Starmer’s premiership. Starmer is, Streeting says, ‘consistently underestimated as a leader’. ‘I was definitely one of those people when he won the leadership who breathed a huge sigh of relief that the Labour party had chosen the path of sanity and electability, but I didn’t think Keir was going to lead us to victory in one term. Poor sod, I thought, he’s going to be the Neil Kinnock isn’t he? Keir always says, “I need to be Kinnock, Smith and Blair all in one”. And he’s done that.’

Streeting had a trickier time than many of his colleagues on Labour’s victory night last year. He only narrowly held on to his seat of Ilford North against a pro-Gaza independent. His majority is now a mere 528. He says the campaign was not all fair. ‘There were two things: one was a pretty ugly propaganda campaign. There was one WhatsApp voice message that was circulating purporting to be me using the most foul language about dead Palestinian children and that definitely had a big impact on the final weeks of the campaign,’ he recalls. ‘I fear for future elections if that’s the world we’re in where people aren’t debating our actual views or opinions or behaviour but instead are trying to discern what’s real and what isn’t. So that was disconcerting.’

A pro-Gaza party also wiped out Labour’s vote in a recent council by-election near his constituency. What does his party need to do? ‘The government is doing the right thing. The Prime Minister is showing the right leadership and what you can’t…’ he pauses. ‘It’s very difficult. In this age of social media, you are bombarded with frankly the sort of graphic images that the ten o’clock news would normally protect you from even after the watershed because it is so horrific.

‘I don’t believe in cutting and running, I’m in it to win it’

‘Just the other day I saw a video of a corpse of a beheaded child being loaded into the back of an ambulance. When you are seeing those things constantly on your social media feed, of course you are horrified by it. It is the really brutal ugly consequence of war and yet I feel powerless as a cabinet minister. So I can understand why there are lots of people in my constituency and elsewhere who are seeing those images and doing the only thing they can do aside from donating to humanitarian causes, which is to express their views at the ballot box. I might have been on the rough end of that, but I can’t really complain.’

Could he be tempted to move to a safer seat? ‘Definitely not. Ilford North is my home. And I don’t believe in cutting and running, I’m in it to win it. I won against the odds in 2015, I won despite the pressures in 2024 and I plan to go into the next election in Ilford North with a track record of turning around the NHS, making a real change for my constituency and changing people’s lives and I’ll be standing on my record at the next election.’

When it comes to Streeting’s politics he is seen as firmly on the right of the party. So, what’s been the worst Tory policy of the past year? ‘It’s a crowded field, isn’t it? I think probably the worst decision David Cameron made was to commit the Conservative party to having a referendum on the European Union and one of the worst things I ever did as a legislator was casting my vote in favour of it. But c’est la vie!’ And Labour? ‘Well, when Jeremy Corbyn was leader it was a target-rich environment! Take your pick under him. Probably the lowest point for me was the Skripal poisonings and casting doubt on the advice.’ Though Streeting himself had a left-wing phase: ‘When I was a student leader involved in NUS politics, I was broadly sensible most of the time but even I at one point signed a “Rethink Trident” letter and now I look back on it I think that was bloody stupid.

‘It’s always been a source of frustration to me that there are leftist traditions that lead people to question – more broadly in the public – whether Labour is committed to law and order, fiscal discipline, national security. Because when Keir states very strong positions on those things when we were in opposition, I didn’t see those as cynical positioning or staking out Tory ground, I saw that as a return to Labour’s proud traditions.’

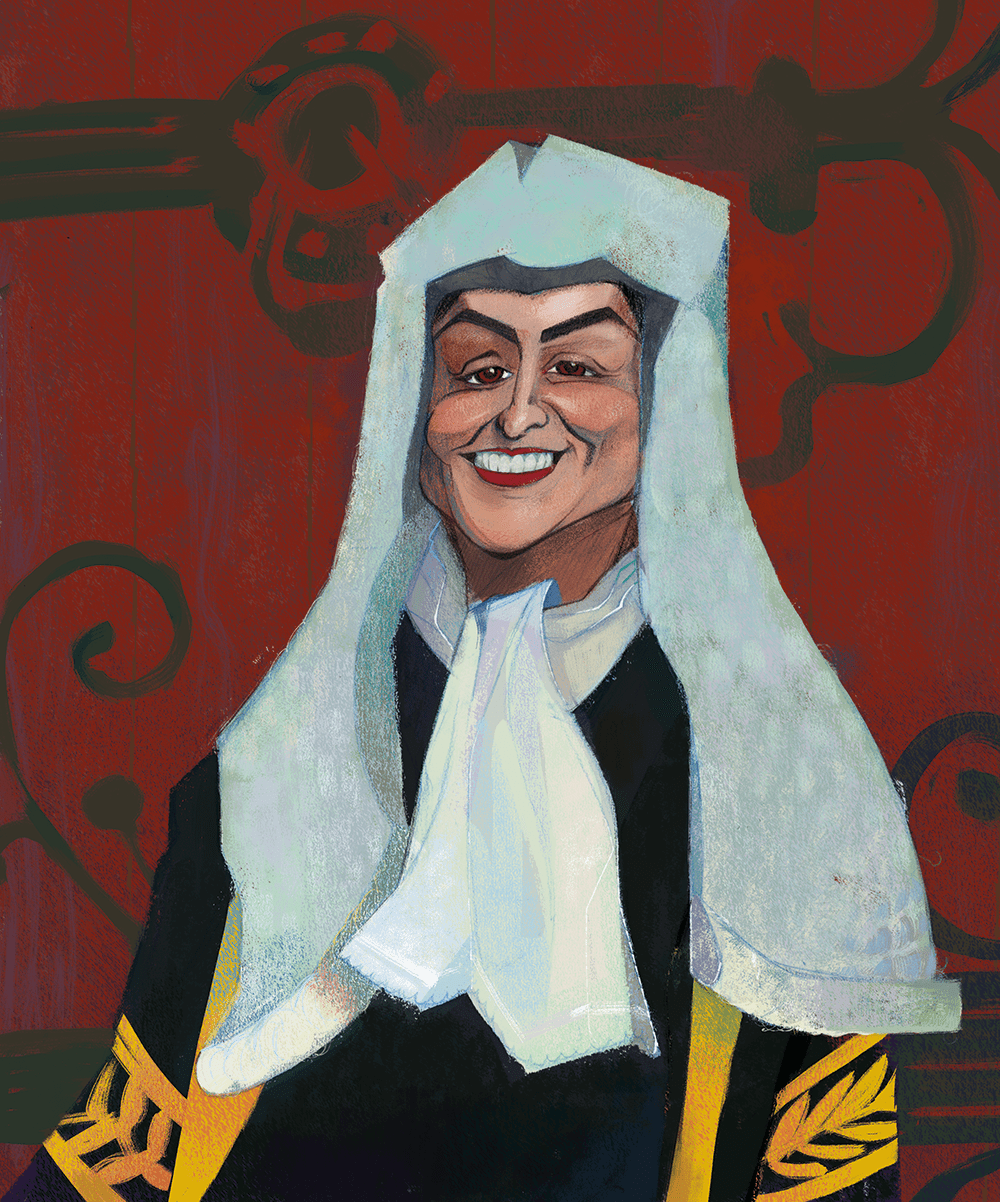

Starmer is not a religious man, but his health secretary is a Christian. Or, in his own words: ‘I’m as soggy liberal Anglican as you can get.’ Streeting found God in his youth, even though neither of his parents were particularly religious. ‘I loved the Church, I had a real connection to my faith growing up to the extent that I was given,’ he says. ‘I wasn’t baptised as a baby, but we were given the option in Year Five or Year Six at primary school of being baptised and confirmed and I wanted to do it. I had to argue with my parents for permission.’ However, he ran into problems when it came to reconciling his sexuality with the Church.

‘I was in the school choir, I used to read in church and then I got to my mid-teens and I started to struggle with what I felt was a conflict between my faith and my sexuality,’ he says. ‘I spent years trying not to be gay as a result. It’s only in recent years that I have really reconciled those two things and felt comfortable in my own skin. There are a number of reasons for that: conversations with our previous Archbishop of Canterbury [Justin Welby], with my local priest… the church I now go to more regularly, and a brilliant book by Michael Coren called The Rebel Christ. The brilliant thing about that book is it not only reconciles my faith and sexuality and my faith and my social liberalism, it also speaks to the thing that I think Christianity is fundamentally about, which is social justice: not walking by on the other side, standing up for the poor and the dispossessed; trying to bring about a fair, more equal, more just society. Those are some of the mobilising tenets of our faith.’

Coren’s book argues that Christians should be there for ‘the rejected and detested, with the poor, the hungry, the jobless, the homeless, the abused, the exploited, the suffering’. It is a powerful manifesto for radical compassion and indicates an anchor of belief in social justice which not every Labour politician can claim.

Streeting’s no puritan, though. When we ask what else he is reading, he starts scrolling on his iPad. ‘I’ve nearly finished Tony Blair’s book on leadership, although actually if I was as Blairite as the stereotype suggests then I should have really finished it already and read it twice by now. Sorry about that, Tony. On the fiction side I’m in the middle of Fire and Blood which is the George R.R. Martin history of the House Targaryen.’ Does he identify as a particular character? Kemi Badenoch previously told The Spectator she connected with Daenerys, mother of dragons, the dictator. ‘You see I love Daenerys Targaryen and I don’t feel the same about Kemi! I’d love to be in House Targaryen. I’m not posh enough to be a Lannister.’

In Game of Thrones, Daenerys unites old enemies, fights for the underdog, tames forces others could not and commands fierce loyalty from old warriors who want both idealism and steel. But, in the end, the ultimate prize goes to another. In the fire and blood of Westminster politics, Streeting stands out as a happy warrior. Whether he will wear the crown depends on what victories he can secure for his followers.

Katy and Michael discuss their interview with Wes Streeting further on the latest Coffee House Shots podcast:

Comments