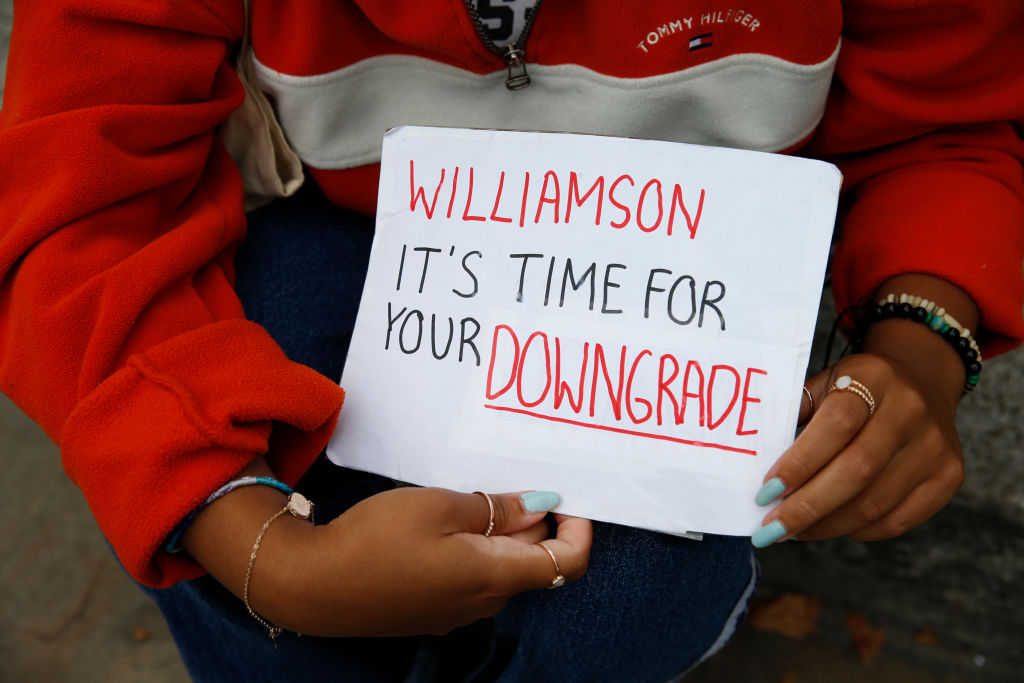

A few weeks ago, I spoke on The Spectator’s podcast about my A-Level results. My story in short: I lost my dream place at UCL to study medicine (my conditional offer was: A*AA) after being downgraded by the algorithm to AABB. As the daughter of a single mother, in a low income household, I’m not exactly the sort of person expected to score top grades (especially not by the now-defunct algorithm). However, with a run of 9s and A*s in my GCSEs, I proved I could beat the odds once, and, had I sat the 2020 exams, I am confident I would have beaten the odds again. But the virus struck – exams were abandoned, and pupils like me never got the chance to prove themselves. You might perhaps think: ‘but didn’t Gavin Williamson U-turn?’ or ‘hasn’t the algorithm been ignored by using Centre Assessed Grades, meaning many students are actually getting high grades?’ This is certainly the case for a number of students, but not ones like myself.

The exams narrative has been running on a false assumption: that if students’ grades were affected, they had been marked up in Centre-Assessed Grades. This is true for some cases, but others were victims of the dreaded deflated grades, where Centre-Assessed Grades were moderated down by the school, before the exam board’s (now defunct) algorithm was even applied. Why would they do that? Put simply, because they feared being marked down even further by the computer. It’s a complicated story, but if it had to be melted down to a few words, it would be: ‘historic data’.

Schools knew that they were up against an algorithm that judged schools by their previous attainment. So if a school had never scored an A* before, and teachers said they had A* pupils, the algorithm would adjust their grades and potentially mark everyone down, assuming – incorrectly and without even checking for supporting evidence – that teachers had overestimated. Hence a dilemma for schools: should teachers give these outlying students the grades they deserve – even if they don’t align with school’s historic data – and risk the whole class being moderated down on the basis of the algorithm, or should they take the safest strategy for the majority? Should they try their luck, or should they game the system and be modest?

Victims of deflated grades had their Centre-Assessed Grades moderated down before the algorithm was even applied

Schools that were modest are, now and quite rightly, up in arms. John Tomsett, the head teacher at Huntington school in York said he would have submitted higher Centre Assessed Grades if ‘we had not been threatened by Ofqual of having a whole cohort’s grades lowered’, due to the school’s historic data – the past performance of previous cohorts. Wallington County Grammar School has written to parents saying ‘knowing how exam boards would moderate’ Centre-Assessed Grades, the school was ‘robust in our procedures to ensure that the overall pattern of results given did not deviate too widely from previous patterns of attainment and the overall expected level of performance’. Williamson’s U-turn, they said, has put ‘the students of WCGS at a gross disadvantage… Because our staff issued Centre-Assessed Grades broadly in line with prior attainment patterns and other schools have not, our students have not benefited from the rampant grade inflation that this practice in other schools has caused. This is inequitable and unacceptable.’

Ofqual, the exams regulator, confirmed in their official guidance (published 3 April 2020) that, because arrangements had to be put in place quickly, they hadn’t developed a ‘common approach to grading across the centre’ and they acknowledge that ‘consequently, it is likely some centres were more lenient in their judgements, and others more severe’.

My school was very cautious. I ended up downgraded from the A*A*A*A* in my UCAS teacher predicted grades to AAAA in my CAGs. One grade lower than my UCL offer. And, in my view, not a fair reflection of my potential. My GCSEs were in the top 5 per cent (ie, they were 9s). The equivalent mark of adequate progress made at A-Level is A* (top 9 per cent). I ended up with As (top 38 per cent). Why now are the professional judgements of my teachers being changed to fit other cohorts’ results?

A second issue in the awarding of Centre-Assessed Grades, at least in my case – as in many other schools – seems to be the over-reliance on mock exams as ‘hard evidence’. Whilst other students were able to focus on their Year 13 mocks, I was focusing on securing my place at medical school (I applied to Oxford, UCL, Imperial and Cardiff) with interviews, entrance exams and prep coinciding with mocks. Interviews, requiring extensive preparation, and entrance exams, based on above A-Level standard science and problem-solving, were not taken into account when assessing Centre Assessed Grades. Neither was the fact that I, like many other medical students, rarely focus on mocks, knowing that we are already on track for A*s in the final exam. Despite the heavy competition and high academic rigour needed to get offers for medicine at university, I received my offers, only to have them ripped away because of my school’s historic data. It begs the question, why have students’ extenuating circumstances (during mocks for instance) not been taken into account?

This is all, I know, a complicated issue. But here’s an example of how this process has worked. Say a class has three or four outliers, strong A* students. We’re talking kids who had been told on several occasions that they were A* students. They have a mock at Grade A*, they have assessed work at A* and their GCSE results were a string of 9s. Yet, their school’s downgraded their Centre Assessed Grades to As. Why? The answer: their school did not receive enough A*s last year. Therefore, they’d end up being moderated down at whole-school level so the algorithm didn’t think that teachers were trying to inflate grades. The A* pupils would be marked down, in case the algorithm downgraded the whole class.

But, realistically, who cares about these anomalous students? Having awarded so many top grades this year to those who probably would not have scored them under the exam (the proportion getting As jumped from 28 to 38 per cent) who would seriously worry about a couple of pupils marked down? The grade inflation means that universities are inundated by students who suddenly now have the grades. There are about 7,500 medical school places nationally, but 8,500 students with the Centre-Assessed Grades that match their offer. I suspect UCL, in my case, barely has room to accommodate medical students who will (now) meet their offer. The chances of it looking seriously at a case like mine – a grade short – are close to zero. Yet, it is perfectly logical that a student who was awarded a Centre-Assessed B grade by their school, has been upgraded by the algorithm to an A* (algorithm grades still stand if it’s the higher grade), but a student who should have been awarded an A* – and only received an A in their mock because they were sitting more important exams at the time (or because the school downgraded to pre-empt the algorithm) – is given a Centre-Assessed A grade.

Most have started to lose hope for a fair, individual appeals process over cases like mine, hesitant about whether a single student can beat a system. As it stands, Ofqual are reluctant to give an appeals process at an individual level (only a school can appeal, and even then, only on certain grounds). This hinders any chance for us. Our cases are too complicated, too freakish – and, let’s face it, we tend to come from neighbourhoods whose voices are not generally heard by those taking big decisions. But I have hope, I know I deserve better.

I still believe that I will be able to fulfil my dream of studying medicine and that what I’ve been through will be acknowledged and remedied justly. The worst thing to be in this exams debacle is a high-achieving outlier. We lost out twice: first, by the algorithm. And now, by sheer fatigue with the entire process: we have become a problem that no one wants to hear about. Swept under the carpet and ignored.

Comments