Ninety years after the ill-fated European peace settlement dictated by the victorious Allies at Versailles, it is fitting that a publisher should commission a series of 32 monographs devoted to the men and consequences of the Peace entitled ‘Makers of the Modern World’.

Ninety years after the ill-fated European peace settlement dictated by the victorious Allies at Versailles, it is fitting that a publisher should commission a series of 32 monographs devoted to the men and consequences of the Peace entitled ‘Makers of the Modern World’. Collectively they will reveal the full extent of debate among the statesmen who redrew the map of Europe in 1919, setting the agenda for international relations in the age of Hitler, Stalin and Churchill.

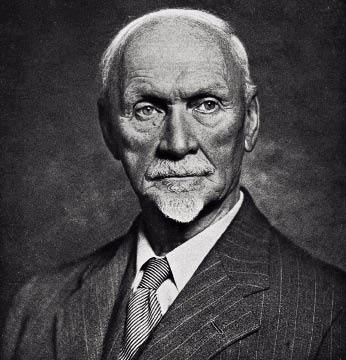

In this contribution to the series, Professor Antony Lentin examines the role of General Jan Smuts, who came to the Paris Peace Conference as Deputy Prime Minister of South Africa. As the most forceful voice in favour of a compromise settlement with Germany, Smuts is the perfect subject for a scholar who has devoted much of his career to unravelling the making of the ‘Carthaginian Peace’.

Smuts was born on his parents’ remote Cape Colony ranch in May 1870, and, although not sent to school until he was almost 13, became one of the most learned statesmen of the 20th century: lawyer, scientist, fellow of the Royal Society and philosopher. He began with a double First from Cambridge, a university he attended courtesy of a well-deserved scholarship between 1891 and 1894. This paved the way for a long political and military career, which saw him sucessively serve as State Attorney of the Transvaal, a legendary guerrilla commander in the Anglo-Boer War (1899-1902), Colonial Secretary and Prime Minister of South Africa from 1919-1924 and 1939-48.

Where Lentin adds to W. K. Hancock’s magisterial two-volume biography is in focussing on Smuts in relation to the Paris Peace Conference. Smuts’ faith in the workability of a lenient settlement was based on what he called ‘the contagion of magnanimity’, which required Germany to be admitted to the League of Nations — an institution he did much to establish. From his own experience he anticipated that the exclusion and humiliation of Germany would not bring peace, but would result in the undermining of the Weimar Republic and the liberal values for which it stood. He spoke with the authority of a man who had himself fought and lost against the British; after which he re-negotiated a lasting peace with the Liberal Prime Minister, Henry Campbell-Bannerman, in 1905. He believed that a similar solution could be found to the conflict of 1914-18, but his more triumphalist colleagues paid him short shrift: Georges Clemenceau called him ‘the saboteur of the Treaty of Versailles’.

Ultimately Smuts had to agree that the demands of the world’s postwar electorates could not be ignored. But he looked back with learned nostalgia to the irenic Congress of Vienna, where the peace of Europe had been secured for almost a century after the defeat of Napoleon. Some might see his eventual acquiescence in the harsh terms of his colleagues as an act of cowardice, but Lentin rightly notes that to have refused his signature would have jeopardised the quasi-independent status of his country as a Dominion of the British Empire.

Smuts’ sympathy for the sufferings of the Germans at Versailles did not turn him into an appeaser of Hitler, as was the case with many who shared his views in 1919. Indeed, as a field marshal in the British army, he was an important confidant of Churchill, who described his abilities in glowing terms. The only cloud that hangs over his legacy is the issue of apartheid, which began under the regime of his successor, Daniel-François Malan, whose National Party defeated Smuts in the 1948 general election. Two years later Smuts was dead.

What went wrong? This is a question that Lentin is perhaps wise not to delve into too deeply, partly because to do so would be like looking through a telescope from the wrong end. Smuts’ views on race were little different from those of the educated elites who ruled the empire from London; detestable from a modern perspective, but a long way short of the institutionalised segregation and open discrimination that came after. Lentin is refreshingly unorthodox when he postulates the likelihood of his subject ‘warming to Nelson Mandela as a kindred spirit’. Both advocated ‘a time for the healing of the wounds’, as the latter declared in his inaugural speech as President in 1994.

As with the other biographies so far to appear in the series, General Smuts is a fast-paced and highly intelligent work, packed with illuminating quotations. The author brings to the table the gleanings of a lifetime’s research on men such as David Lloyd George and Woodrow Wilson, whom he clearly holds accountable for much of the later history of the 20th century. Whether readers choose to go all the way with him or not, his book will remind them that not all politicians at Versailles were monsters, nor is democracy necessarily the best means of resolving a world crisis. The Conference was, in Churchill’s words, ‘a turbulent collision of embarrassed demagogues’.

Comments