Elaine Herzberg was pushing a bicycle laden with shopping across a busy road in Tempe, Arizona in 2018 when she was struck by a hybrid electric Volvo SUV at 40mph. At the time of the accident, the woman in the driver’s seat was watching a talent show on her phone. The SUV had been fitted with an autonomous driving system consisting of neural networks that integrated image recognisers. The reason Herzberg died was because what she was doing did not compute. The autonomous driving system recalibrated the car’s trajectory to avoid the bicycle, which it took to be travelling along the road, only to collide with Herzberg, who was walking across it. She became the first casualty of artificial intelligence.

Facebook can know more

about you than you

know about yourself

What’s particularly poignant about this tragedy is that autonomous systems such as the one that killed Herzberg are, like most AIs, modelled on human intelligence, and yet are predicated on the idea that they can do that thinking better than us. The DeepMind Professor of Machine Learning at Cambridge, Neil Lawrence, calls such AIs human-analogue machines (HAMs). These HAMs attempt to emulate human behaviour. He writes: ‘Neural network models that emulate human intelligence use vast quantities of data that would not be feasible for any human to assimilate in our short lifetimes.’ A human driver, in the same circumstances, he argues, would have slowed down: ‘Delaying action is one of the ways we respond to the gremlin of uncertainty.’ AI has a problem identifying such gremlins. The car ploughed on, dragging Herzberg 20 metres down the road.

The great difference for Lawrence between human and machine intelligence is that the former is embodied. We are locked in, constrained by our physical brains. That, you’d think, is all to the advantage of the unconstrained machine intelligence. Chillingly, Lawrence discloses, Facebook can know more about you than you know about yourself – which in my book is just another reason to come off social media. Yet I’m also beguiled by the possibility of ChatGPT writing my reviews while I sip martinis under the duvet.

For Lawrence, matters aren’t so simple. Humans are glacially slow in thinking terms compared to AI, but at best we are capable of things beyond the wit of artificial intelligence – doing the right thing, pausing the algorithmic treadmill to reflect, and (as far as I can see) driving with due care and attention. AI cannot replicate the evolutionary nature of human intelligence, nor its social character.

Lawrence, who as director of machine learning at Amazon was in charge of the world’s largest machine intelligence, dissents from the stupid idea that captivates many software engineers, tech oligarchs and giddy trans-humanists – namely that the machine adapts to us, rather than the other way round. Herzberg’s death suggests otherwise. ‘The danger we face is believing that the machine would allow us to transcend our humanity,’ he writes. The German media theorist Friedrich Kittler once wrote that we adapt to the machine, not vice versa; we become reflections of our technologies, rather than our technologies obligingly extending our dominion over the world.

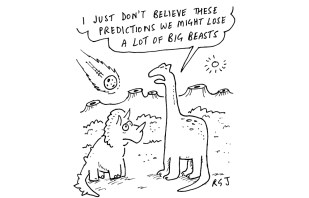

Some big-brained humans have worried about our looming obsolescence. Stephen Hawking argued that artificial intelligence ‘could spell the end of the human race’ while, in his final interview, Daniel Dennett told The Spectator’s Gus Carter: ‘It could be the end of civilisation.’ Lawrence is worried, too, but swerves such doom-mongery:

Across our history we have developed new tools to assist us in our endeavours and the computer is just the most recent. But that’s all the computer ever should be – a tool.

His fear is that AI is becoming more than a tool – that we are adapting to it and growing more stupid in the process:

We are sleepwalking into slavery – into cognitive dependency in our professions. These models do 80 per cent of our work and leave us 20 per cent of the work to do, but our agency is diminishing as we are becoming less and less efficient at doing the 20 per cent.

The corollaries are terrifying to contemplate. As we know from the Horizon scandal involving the wrongful prosecution of British postmasters and mistresses, ceding human tasks to out-of-control machines can be disastrous. But, Lawrence writes, we haven’t seen anything yet:

We are sowing the seed for 10,000 Horizon scandals right as we speak. We are looking at the same loss of power and understanding among ordinary people. AI is empowering people at all scales to write bad programs… It was those on the margins that were and will continue to be affected.

The great joy of this discursive book – one of the best on the perils and boons of AI so far written – is to show that technological innovation has both liberated and enslaved us. Or, as the French philosopher Paul Virilio put it: ‘The invention of the ship was also the invention of the shipwreck.’

Lawrence found himself describing his work in AI to a receptionist at London’s Natural History Museum, who commented sagely: ‘So it’s fire, then?’ It is indeed. AI can do many things for us, but, as with fire, it is folly to suppose no one will get burned. Lawrence draws the parallel with the advent of language, which he supposes was a technological boon aimed at helping us communicate accounts, instructions and laws more effectively, before being taken over by the clergy. Only with the printing press was knowledge democratised again. (Catholics may want a right of reply to this.) History, he thinks, is repeating itself:

We are seeing the control of language again. The new information structure is the machine, and the software engineers are the new scribes, but they have no idea of a moral code or social duties. The tech companies are the modern guilds, their power arising from the very nature of the information structure.

This is an unexpected perspective from a man who worked for Jeff Bezos, is friendly with Mark Zuckerberg and whose Cambridge post is bankrolled by Google. What he seems to be suggesting is busting down the tech bros to size, and making AI work for us. It is symptomatic of the shortcomings of even really evolved human intelligences that he doesn’t suggest how. ‘We must avoid becoming a technocracy run by AI making our decisions,’ he concludes. We must. But it would be human, all-too-human, to doubt that we will.

Comments