N.B. This review was published without its final two paragraphs in the 18th December 2010 issue of The Spectator. These paragraphs have been reinstated for the online version below.

These volumes — four for now, and a further six to come — are saddled with a title redolent of lantern lectures delivered in Godalming, say, round about the time that Rorke’s Drift became legendary overnight. The Image of the Black suggests people, or things, of a certain stamp. Penny blacks, so to speak: picked out with tweezers, profiles raised, their blackness being their distinction, their black face value assessed within the swelling majesty of Western Art.

That was the idea, anyway, back in the Sixties when Dominique Schlumberger de Menil, co-founder of the de Menil Foundation in Houston, Texas, thought how good it would be to assemble a photo archive of fine art down the ages in which the ‘Image of the Black’ could be seen to figure, no matter how marginally. The thought was that, at a time when segregation still obtained, this would be Southern hospitality of sorts, extending to Afro-Americans a helpful hand, showing them pictures to identify with and feel good about. Mrs de Menil argued:

Many works of art contradicted segregation. A sketch by a master could reveal a depth of humanity beyond any social condition, race or color. So why not assemble these artworks in an exhibition or a book? With such a naïve approach, a serious enterprise was started.

Within a few years some 30,000 photographs were on file. Selections from these were published in the late Seventies which, expanded and rendered more attractive with a wealth of colour reproductions, now serve as the first stages of a projected edifice of inspirational empowerment underpinned with scholarship.

The naïve approach has been bulked out with discursive contributions (‘Cushites and Meroites: Iconography of the African Rulers in the Ancient Upper Nile’, by Jean Leclant; ‘Rembrandt’s Africans’, by Elmer Kolfin) to create an open-ended opus. The last word will be had in The Twentieth Century and Beyond: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Age of Obama. This is scheduled for publication in Spring 2015. Following that, maybe there should be an updated reversion of the enterprise. How about The Image of the White in African Art? Such images exist, and they could do with collating. Why is it that the words ‘The Black’ can occur in print on spines, covers and title pages, a term branded with the definite article, whereas ‘The White’ would look … odd, let’s say?

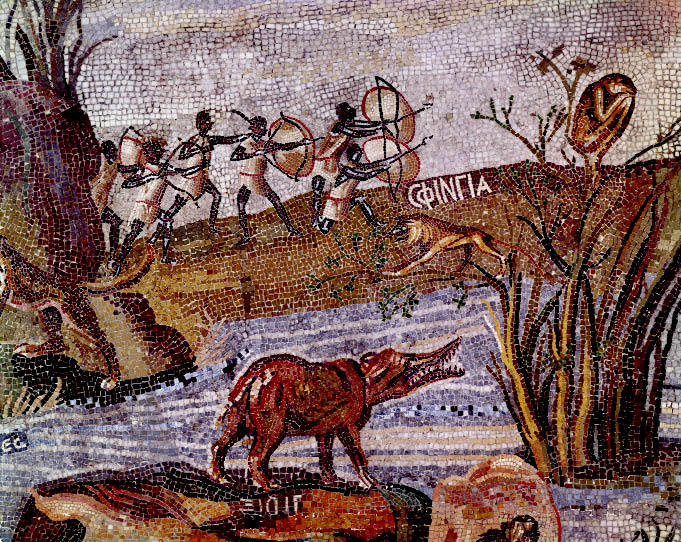

Moving on, the volumes so far are a treasury of paintings and sculptures of people down the ages, taking in many strands of ritual, classicism, artlessness and humanity. Art history proceeds here at the gallop: From the Pharaohs to the Fall of the Roman Empire; From the Early Christian Era to the Age of Discovery and From the Age of Discovery to the Age of Abolition, of which only the first third — taking us into the Baroque — is available as yet. This stretch ends with a flamboyant painting by Karel van Mander III in the Gemaldegalerie, Kassel: ‘Theagenes Wrestling the Ethiopian Giant’, c. 1640, a work heavy with suppressed eroticism. Of it Dr Joaneath Spicer, of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, comments: ‘The black and white bodies are so pressed together in combat, belly to belly, that one imagines their sweat mingling.’ Quite so.

The intermingling of image bank and scholarly knowhow makes for hedged assertions. (‘So it is almost certain that Rembrandt actually knew real Africans…’) As the survey proceeds, from Tutankhamen’s tomb onwards, it ticks away with train-spotter persistence, focussed all along on the need to pick out figures with the relevant features. Restricted as they most often are to spear-carrier or bystander roles, these figures serve as either retinue or odd ones out; no amount of contextualising commentary can advance them; they are what they are: more or less incidental. Even those promoted as savant royalty (Balthazar, one of the Three Magi) or as saints (St Maurice, converted from white to black in 13th century Magdeburg for Bohemian political ends) come wreathed in the distinction of being unusual. These are exceptions rather than the norm. Yet occasionally a true portrait slips through. Prominence is awarded to the black archer stood third from the left in Benozzo Gozzoli’s ‘Journey of the Magi’ in the Palazzo Medici in Florence. He’s there for a good Medici reason: just ahead of him in the gorgeously apparelled processional train is Lorenzo de Medici promoting himself among the Magi. His black presence is a tribute to the greatness of the Medici, bankers to the known world.

For love of art and with benevolent purpose Dominique and John de Menil bought art and commissioned art, notably the Rothko Chapel next door to the Menil Collection in Sul Ross Street, Houston. They were latter day Medicis. Guided by impulse, whim and generous convictions they realised any number of projects that without them would not have been practicable and they did so regardless of standard priorities. For many years, for example, their foundation went on paying David Sylvester to compile the Magritte catalogue raisonne, a venture of Casaubon proportions. They ranged widely and imaginatively, keen to show how art connects and keeps on connecting. That said, why quibble over the motives prompting the scheme and theme of ‘The Black in Western Art’? Better to applaud the trawl. For here, conveniently gathered in alongside hundreds of lesser works from many cultures, are such marvellous images as the sandstone statue of the (black) St Maurice in Magdeburg Cathedral and that supreme Velazquez, the portrait of Juan de Pareja, his slave and fellow painter.

Comments