To understand Bob Dylan’s Fragments – Time Out Of Mind Sessions (1996-1997) – due to be released on Friday – you have to go back half a century to the release of the Beatles’s Let It Be. As millions of fans around the world bought the band’s final album, Paul McCartney was horrified. This was not the disc he had conceived: some of the most cherished songs in his oeuvre had been hijacked by superstar producer Phil Spector, who stamped his trademark ‘Wall of Sound’ during the album’s post-production process, filling it with lavish embellishments.

Fast-forward to the mid-1990s and another legendary songwriter was at loggerheads with a different superstar producer, then still a dominant force in the era of mega-selling records. Daniel Lanois might not be a household name like Spector, but in the 1980s and 1990s musicians queued for his services and trademark swampy, atmospheric sound. He was behind a string of hits for stars including U2, Emmylou Harris and the Neville Brothers.

In 1996 Dylan, who hadn’t released any original material since Under the Red Sky six years earlier, met with Lanois. They had worked together on Oh Mercy in 1989 after Lanois was recommended by Bono. Although they hadn’t kept in touch, Dylan wanted Lanois’s verdict on some lyrics he had written: was there enough to make a record? Lanois was receptive. ‘They had a lot in them,’ he would later say. ‘They had regret and hope, beauty and optimism. A lot of life experience. They were so complex.’ Dylan hadn’t written any melodies, but gave Lanois a collection of old Delta blues records to illustrate the raw sound he wanted.

The relationship between Dylan and Lanois was fraught, filled with creative differences, tantrums, fights, and even smashed guitars. But what came out of it was a seminal record

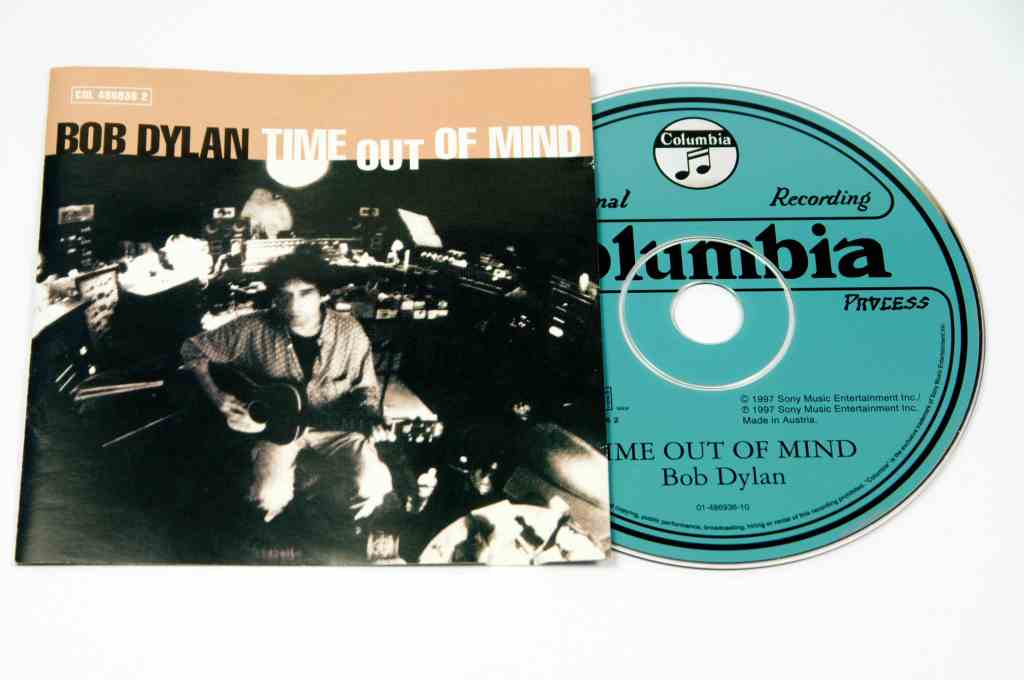

From September 1996 to March 1997, they worked together in two studios, beginning in a disused theatre in California, before moving to Miami’s Criteria Studios. Their relationship was fraught, filled with creative differences, tantrums, fights, and even smashed guitars. But what came out of it was a seminal record: Time Out Of Mind. Dylan’s 30th studio album was widely accepted as his most complete work since Blood on the Tracks in 1974, and swept the board at the 1998 Grammys, winning Album of the Year, Best Contemporary Folk Album and Best Male Rock Vocal Performance. Yet Dylan was disappointed with Lanois’s artificial edits post-production, just like McCartney had been with Let It Be.

‘My recollection of that record is that it was a struggle,’ Dylan said four years after its release. ‘A struggle every inch of the way. Ask Daniel Lanois, who was trying to produce the songs. Ask anyone involved in it. They all would say the same… that album sounds to me a little off.’

Of course, Dylan’s and McCartney’s clashes with their producers are very different (not least as McCartney was one of four when it came to decision-making). But they illustrate the creative conflicts that once took place between legendary musicians and star producers. You’d be forgiven for assuming a Beatle and a future Nobel Laureate would get their own way, but there was a time when this wasn’t the case. Lanois would be the last producer Dylan worked with, choosing to do it himself under the pseudonym ‘Jack Frost’ ever since.

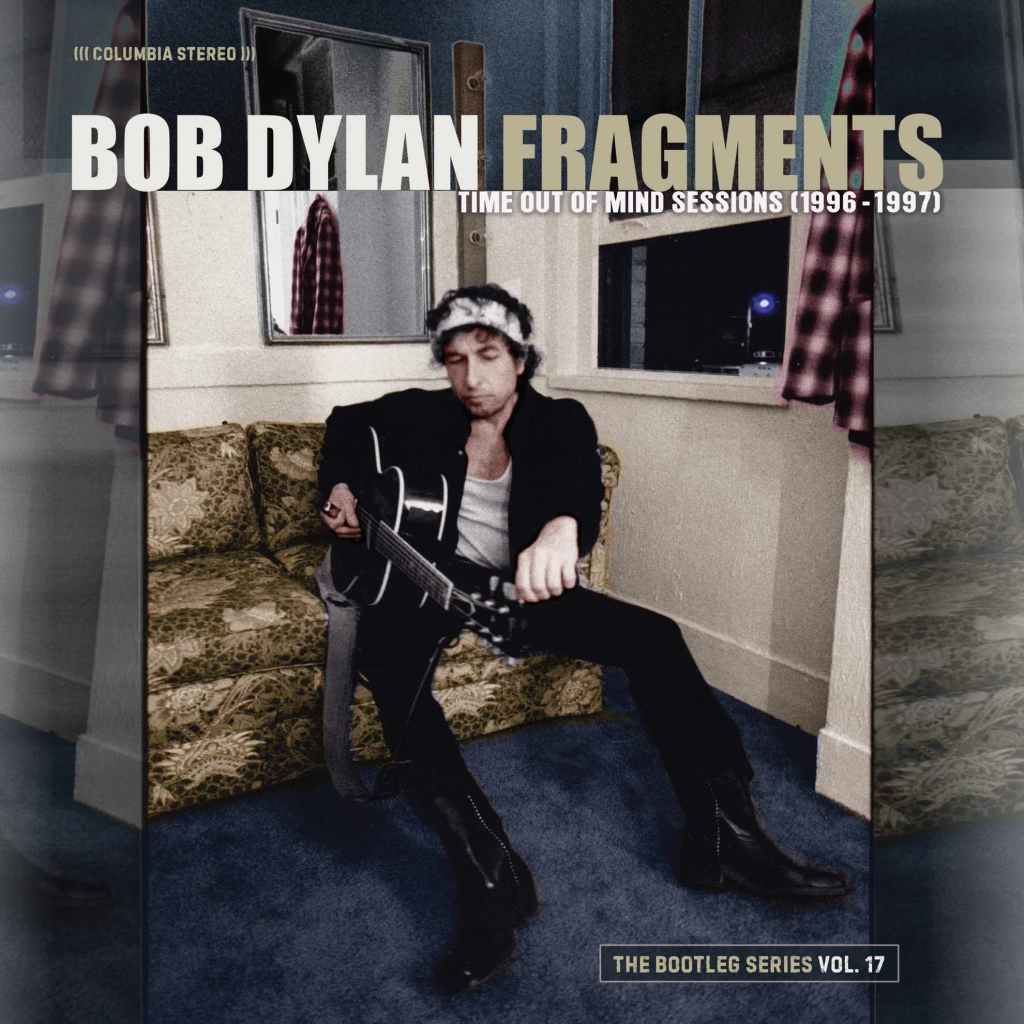

Now, however, just as McCartney released his own remixed version of Let It Be in 2003 to lose Spector’s input, the opening disc of Dylan’s 17th ‘Bootleg Series’, Fragments, features the album remixed by Michael Brauer with Lanois’s embellishments stripped back. It gives listeners the chance to hear the record as Dylan wanted it. The five-CD box set also includes alternate takes and demos of songs from the sessions, live performances of the album’s songs, and various takes on four songs that never made the cut.

At times you have to listen closely to hear the differences between the remixed album and the original. Elsewhere, it is more obvious that Lanois’s heavy reverb and artificial effects have been dialled back. In its place is an album that is bare and spectral, and sounds ‘up close’, almost as if you’re in the studio hearing it live.

The result is that you notice more instruments in the mix – not surprising considering how many musicians there were. Dylan brought in multiple players for every instrument, from star session players such as drummer Jim Keltner and legendary blues axeman Duke Robillard to members of Dylan’s touring band, including pedal steel player Bucky Baxter and long-standing bassist Tony Garnier. There were no less than four drummers during the sessions.

On the remixed album you can hear the different placement of amps, with some guitarists further forward than others, which is down to Lanois’s clever set-up in the studio. Yet the effect comes alive more in this remixed version (particularly on ‘Cold Irons Bound’).

Without doing a disservice to Lanois, the remixed version sounds marginally better (and certainly fresher) than the original, something many Dylan fans will be surprised about considering the esteem the original record is held in.

There is another question Fragments answers, too: are earlier outtakes and alternative versions of the songs better? Besides lyrical alterations, they can be heard in different keys and tempos to the final takes.

‘Highlands’, the album’s 16-minute, 20-verse masterpiece, is its main gem. The alternative version is played at a faster tempo with a more pronounced beat, and stripped down to a mere 18 verses. The music is grittier and bluesier, making it much more of a foot-tapper than the final cut. This version is made in large part by the sublime pedal steel playing, which builds the song’s tension. Throughout, it hovers menacingly in the background like a distant echo, before dropping in to play distorted licks that weave around Dylan’s singing to emphasise certain lines (e.g. ‘Insanity is smashing against my soul/ You could say I was on anything but a roll’).

‘Highlands’, the album’s 16-minute, 20-verse masterpiece, is its main gem. The alternative version is played at a faster tempo with a more pronounced beat, and stripped down to a mere 18 verses

One of the album’s singles is ‘Love Sick’. Lanois said he treated Dylan’s voice like a harmonica, over-driving it through a small guitar amplifier. There are two alternative versions on Fragments without this effect; they sound better for it.

There is a fantastic up-tempo, bluesier take of ‘Till I Fell in Love with you’ with some heavy guitar chops and a raw new lyric that Dylan practically spits out: ‘Claustrophobia is breathin’ into my face’. The second version of ‘Can’t Wait’ also has greater energy, driven by Robillard’s unleashed guitar licks. It’s proper rough-and-ready blues.

People used to pay good money for unofficial bootlegs of Dylan shows from the late 1990s and early 2000s. So it is little surprise that the live recordings on Fragments of Time Out Of Mind tracks are exquisite. Dylan’s voice was clean and clear during this period, and his band line-up was tremendous. The dynamic relationship between guitarists Larry Campbell and Charlie Sexton, in particular, provided real energy. The standout number is a tender, slow jazz version of ‘Tryin’ to get to Heaven’ from Birmingham in 2000. There is a smoking version of ‘Cold Irons Bound’, too, taken from Oslo in the same year. Meanwhile, ‘Can’t Wait’ performed in Nashville, Tennessee, demonstrates Campbell’s melodic playing during a long fill which gives him space to solo, taking the song to a crescendo (something Dylan’s current guitarists aren’t given the space to do).

Since the first Bootleg Series in 1991, when fans discovered ‘Blind Willie McTell’ – which Dylan cut from Infidels in 1983 and which is considered one of the best songs he’s ever written – there has been huge focus on what he leaves off his albums. Here the final disc contains versions of the four tracks that did not make the cut. ‘Dreamin’ of You’ can be heard as a tender slow blues ballad carried with assertive piano chords. The two takes on ‘Marchin’ to the City’ are nothing special. It is the other two tracks, ‘Mississippi’ and ‘Red River Shore’, that are of real note.

‘Mississippi’ perhaps best demonstrates the tempestuous relationship between Dylan and Lanois. ‘[He] thought it was pedestrian,’ Dylan told Rolling Stone. This extraordinary love song from the perspective of a drifter was re-recorded on Love and Theft in 2001. Years later, Dylan said the track ‘wasn’t recorded very well’ with Lanois. ‘Thank God, it never got out’.

On Fragments, there are three versions of ‘Mississippi’. We have heard alternative versions before on The Bootleg Series Volume 8: Tell Tale Signs in 2008. But these takes still provide a fascinating window into how Dylan developed it from a mournful stomping blues to a swinging waltz – although none of the versions here are as good as the one on Love and Theft.

‘Red River Shore’ might be one of the finest songs Dylan has ever written. The narrator reminisces about a lost lover; by the end, it isn’t clear if she ever existed. It is staggering that it was ever bumped from the album. Veteran keyboardist Jim Dickinson, who played on the sessions, said it was ‘the best thing we recorded’. We first got a glimpse of it on Tell Tale Signs; on Fragments we get two more versions. That Dylan and Lanois couldn’t get to a place where Dylan was happy with it says a lot about the pair’s conceptual differences.

The final song the pair recorded was the album’s standout, ‘Not Dark Yet’. Lanois thought an early version was a possible hit, but Dylan wanted it slower, murkier – darker. During the final session, Lanois instructed Dylan to try the song in another key. Dylan, however, wasn’t going to play ball. ‘We did it in E flat. And we did it in B flat,’ he said. ‘And you know what? If you ain’t got it now, you ain’t getting it.’

The two alternate versions on Fragments show not only its progression, but their strong artistic differences. The first take preferred by Lanois is too upbeat, which detracts from the lyrics (some of which are different). The second take is sung and played with the passion and fervour of the deeply moving album version.

As a child I can remember hearing ‘Not Dark Yet’ on repeat; it is my earliest memory of Dylan. I was six when Time Out Of Mind came out, and my old man played it over and over again. I can remember being moved by it, though confused by Dylan’s voice. The other night I played my dad the slow alternate take of it. ‘It is the most perfect song,’ he mused. ‘You can play it at my funeral.’

I’m hard pressed to think of a more poignant song. Not only is the narrator stuck with a burden greater than he can bear, he is so imprisoned in his troubles that not even death will provide refuge. The concluding verse nods to Pirkei Avot (4:22) of the Talmud: ‘I was born here and I’ll die here/ Against my will.’ (‘Against your will you were created, and against your will you were born, and against your will you live, and against your will you die.’) The song ends with the narrator resigned to his depressed, lonely fate: ‘I don’t even hear the murmur of a prayer’. Remixed or not, it would be the first song on any Desert Island Disc for me.

Comments