The last time I saw Benazir Bhutto was at Oxford, over champagne outside the Examination Schools, when she inquired piercingly of a subfusc linguist, ‘Racine? What is Racine?’ Older and richer than most undergraduates, and as a Harvard graduate presumably better educated, she was already world famous, and was obviously not at Oxford to learn about classical tragedy.

The last time I saw Benazir Bhutto was at Oxford, over champagne outside the Examination Schools, when she inquired piercingly of a subfusc linguist, ‘Racine? What is Racine?’ Older and richer than most undergraduates, and as a Harvard graduate presumably better educated, she was already world famous, and was obviously not at Oxford to learn about classical tragedy.

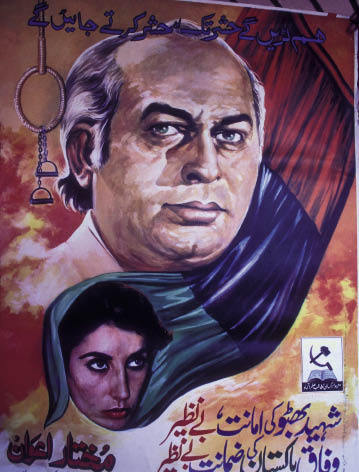

It is unusual, as Benazir’s niece Fatima points out in Songs of Blood and Sword, for a Bhutto to die a natural death. Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Benazir’s father and Fatima’s grandfather, had been at Christ Church (Benazir was at LMH and Catz), and had recently been denied an honorary doctorate, having supposedly burnt down a university. As Prime Minister of Pakistan he was besieged by enemies, and that July he would be arrested on a murder charge by the Terry-Thomas lookalike, General Zia. Benazir was at Oxford not to imbibe culture but to make politics: to wave the flag and bang the drum, to plot revenge, and to become — as her father had not — President of the Union.

As a political nursery, the Union’s advantage over the student union is not so much the obvious one — that it is a toy parliament with access to actual prime ministers and presidents — but that its elections dispense with such fripperies as party and policy to focus on the real business of politics: the management of personal alliances and rivalries by means of flattery, deceit and betrayal, not to mention bribery, threat and blackmail. As an operator or ‘hack’, Benazir was in a different class to the natives (Damian Green, Colin Moynihan), and her campaign of Michaelmas 1976 was rated the most ingeniously corrupt in memory.

Her family had taught her all about the business of politics, and more than Racine could about classical tragedy, and that summer 33 years ago she was already starring, as first female President, in a classical tragedy of her own.

In the decades since — as Benazir became her country’s first female Prime Minister, and was removed from office on charges of corruption; was returned to power in blatantly rigged elections, was removed again on similar charges, and so on — I took a foolish nostalgic pride in her mature practice of Union machine politics. And after Zulfikar was executed in Rawalpindi in 1979, and Zia killed with the US ambassador in a suspicious air crash in 1988 (when Benazir was first elected prime minister), and after all the murders that occurred in her orbit, of her opponents, friends and siblings, I was saddened but not much surprised to watch on television as her tragedy ended in murder, in Rawalpindi in 2007.

Fatima Bhutto is not a fan of her aunt, whom she recalls as ‘a consummate bully’. Her book — a ‘journey of remembering’ — opens with a vivid account of the death of her father Murtaza, Benazir’s younger brother, and a promising liberal politician (Harvard and Christ Church). In September 1996, two days after Murtaza’s 42nd birthday, his house (where the teenage Fatima slept in an old bomb shelter) was surrounded by his sister’s tanks, and soon afterwards he was shot dead by his sister’s police.

At the end of her journey, Fatima Bhutto returns to her father’s murder, and in the meantime supplies a hectic, angry and sporadically witty history of her family and country. The Bhutto tribe originated in the deserts of Rajasthan, from which it was driven by feud to Sindh, where Bhuttos prospered as bullies. In 1877 Doda Khan Bhoota was commended by the Viceroy for loyalty to the Raj, and in the 1930s his great-grandson Sir Shahnawaz was appointed Chief Minister of Gunaghar, in what became Pakistan.

Shahnawaz’s son Zulfikar (‘Zulfi’), who before Christ Church had read Marx at Berkeley (and whom Fatima frankly worships), wanted to redistribute zamindar, wealth and power (at Partition the country was owned by 21 families; 27 by the millennium), and to assert Pakistan’s independence from the US — which is why, according to Fatima, Kissinger permitted his execution.

Benazir, on the other hand, having secured the succession by the murder of one if not both of her brothers, stole billions of dollars and left Pakistan ‘a nuclear-armed state that cannot run refrigerators’, infested with Taliban, indifferently bombed by American drones, and with Asif Ali Zardari, her larcenous widower, as President.

I cannot vouch for the accuracy of Fatima Bhutto’s book — her belief in astrology raises doubts, as does her airbrushing of her cousins, Benazir’s children, from the family tree, from the index and from history, and nor is it easy to believe that Benazir thought seriously about marrying Yasser Arafat — but it certainly lives up to its violent title. The Bhutto story is one of perpetual blood feud, of tragedy more in the vein of Webster than Racine.

Comments