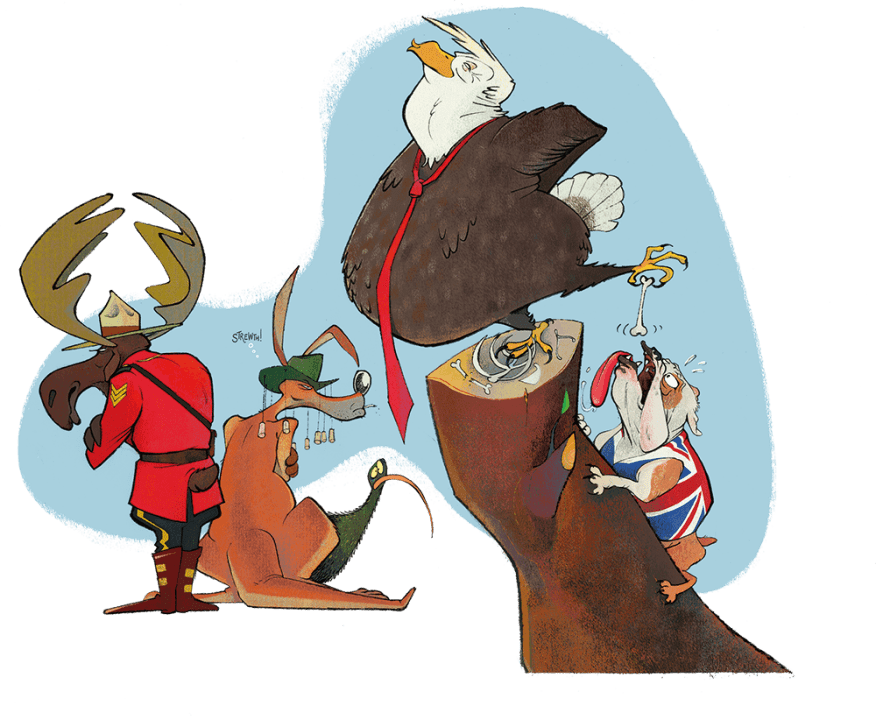

It is the great good fortune of Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand to be united by a common language, and a misfortune of even greater magnitude that they share that language with the United States.

America is a very different country to the four Commonwealth realms sometimes brigaded together under the ugly acronym ‘Canzuk’. It has a different constitution, a different culture and a very different history. Where for many years the four were partners (if hardly equal partners) in the common project of the Empire, the United States was, from its foundation, a determined and eventually successful enemy of the same.

For Conservatives who tend to dream of one united Anglosphere – the ‘English-Speaking Peoples’ of Churchill’s great history – it can sometimes be uncomfortable to recognise that America is the problem child in the family. However, the advent of Donald Trump in the White House should serve as a powerful reminder not only that our interests are not always aligned but that America First can often mean Anglo Conservatives are the big losers.

America only slowly, and reluctantly, shouldered its global responsibilities as leader of the Anglosphere. And even then its underlying strategic position – scepticism of the old Empire – never wavered. Entering the second world war scarcely less tardily than the first, its support for Britain entailed draining our foreign currency and gold reserves before letting us fight the war on credit, with the debt called in the day hostilities ceased.

J.D. Vance may well now rue that President Eisenhower finally pulled the rug out from beneath the feet of European strategic autonomy during the Suez crisis. But it marked the culmination of a long-standing and ruthlessly executed diplomatic posture dating back, more or less, to 1775.

Yet in the decades since, various factors – first the exigencies of the Cold War and vainglorious delusions about being Greece to Washington’s Rome, and latterly America’s sheer economic might and the dominance of its popular culture in a world made smaller by new media – have led generations of politicians elsewhere in the Anglosphere to blind themselves to these facts.

What mattered was that Churchill’s bust was in its rightful place and our special relationship was, per Love Actually, ‘still very special’. (Washington’s real special relationship is, of course, with Ireland, a country allowed to prop up its GDP by appropriating American corporation tax receipts while republican terrorists raise funds in Boston bars.)

Nigel Farage is scrambling to put clear blue water between himself and the Republican administration

For Conservatives in particular in recent years, not just in Britain but in Canada, Australia and New Zealand, America was the shining city on the hill, the ideological north star and the keystone in the alliance. But is the right now paying the price for our Atlanticist delusions? Trump’s second term has completely reversed the fortunes of the Conservative party of Canada, until recently on track for a historic landslide, and in Australia the Coalition, led by the Liberal party, is now on the back foot against Anthony Albanese’s previously embattled Labor government.

Nigel Farage, until recently touting his close relationship with Trump as a potential national asset, is scrambling to put some clear blue water (the whole Atlantic, ideally) between himself and the Republican administration. Even New Zealand’s recently elected right-wing government is showing signs of stress, with splits between the free-trading National party and protectionist New Zealand First.

There is no doubt therefore that Trump and his policies have had a significant impact on both the Canadian and Australian elections – it would be extraordinary if it were otherwise. But even as the Trump effect is noticeable, what matters more is the need for the Canzuk parties of the right to attend more closely to the specific geographies that they operate within and adapt to very different local conditions.

We cannot know for certain, of course, what has actually happened in either country until the votes are counted. In Canada, for example, some pollsters seriously suspect a polling miss is in the offing.

Nonetheless, Pierre Poilievre’s Tories have undoubtedly been dealt the heaviest blow by Trump’s return to the Oval Office. His belligerent and belittling attitude towards the country he calls ‘the 51st state’ has granted the incumbent Liberals a classic ‘rally round the flag’ effect, and central casting could hardly have provided a better candidate than Mark Carney to maximise the contrast with the President.

The modern Conservative party of Canada is also the most vulnerable of any centre-right Anglosphere party to Republican cultural influence, for the simple reason that the political culture and economic condition of its heartlands in Western Canada – rural and resource-led – most closely resemble those of red-state America. And if the current polling is borne out in the results, the critical factor will likely have been Trump refocusing the election campaign away from the economy, housing, the cost of living and immigration (all issues on which the Tories still lead) to the existential question of Canadian identity.

Central casting could hardly have provided a better candidate than Mark Carney in contrast to Trump

That such an election favours the Liberals is remarkable, given that only recently Justin Trudeau proudly declared Canada the world’s ‘first post-national state’ and that it was their party, with Lester Pearson’s changing of the flag in the 1960s, which kicked off the process of dismantling the old Canadian identity and, in deference to Quebecois sensibilities, not really replacing it.

The diagnosis is not terminal for the Canadian right. No party which leads on all the crucial economic questions can be written off, and no victory can long protect a government elected without a plan to address such concerns (as Sir Keir Starmer can attest).

If the election prompts the Conservative party to try to repair the frayed threads that once united the territories it needs to win – the West, Ontario, the Maritimes and Quebec – that is all to the good. Historically, they ought to be much more plausible contenders than the ‘post-national’ Liberal party for the mantle of safeguarding Canada’s nationhood; if they fumble that ball, it is their own fault.

The Australian right is likewise largely the author of its own misfortunes. The Labor government’s defeat in the 2023 referendum on the ‘Aboriginal Voice’ created a generational opportunity for the Coalition, which it has failed to capitalise on largely because it has, in Peter Dutton, a leader who has never led Albanese as preferred prime minister.

In light of that, it isn’t all that surprising that Labor has gained ground as the election approaches. It has certainly been helpful to Labor to paint parts of Dutton’s agenda as Doge-adjacent (he has recently U-turned on trying to force public-sector employees back to the office), but such mud would not stick to a candidate with a better feel for the electorate.

If the Liberal party has an America problem, then, it runs deeper than a mere backlash to Trump’s tariffs, and is reflected better in the simple fact that too many of its politicians seem not to recognise, let alone share, the deep aversion of most Australian voters to the President and his style of politics.

They are scarcely alone in this failing. It is widely acknowledged that the internet makes it much easier to form communities bounded by interest rather than geography, and this is as true of politics as anywhere.

An Australian, British, Canadian or Kiwi politician doesn’t need to go to the Conservative Political Action Conference outside Washington to become steeped in American political culture. They can follow a state-level election in the US as easily – perhaps, given the state of local media, more easily – as developments in their own constituencies, and it has been decades since their newspapers and broadcasters confined reporting on America to the international pages (where it belongs). On top of which, they’re all on X.

So however much the dawn of this second Trumpian age might be hurting the electoral prospects of the right across the Canzuk nations in the short term, it could yet be worth it if (and it is a big if) it makes their politicians realise that for all its charms and virtues America really is a different country, playing by entirely different rules, and which has very different interests. History really counts. When the US finally shakes off the burdens of global leadership with which Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt contrived to freight it, all Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom will have is each other.

Comments