Britten’s Peter Grimes turns 80 this June, and it’s still hard to credit it. The whole phenomenon, that is – the sudden emergence of the brilliant, all-too-facile 31-year-old Britten as a fully formed musical dramatist of unignorable force. W.H. Auden had urged him to risk everything – to step outside his admirers’ ‘warm nest of love’ – and in the first moments of Peter Grimes, Britten does precisely that. The folk-opera bustle of the opening tribunal scene dissolves into the desolate bird cry of the first Sea Interlude and straight away, you’re in the presence of something unimaginably vaster and more true. It pins you to your seat.

That was certainly the impression I had from Tomas Hanus, conducting the orchestra and chorus of Welsh National Opera. Not the only one, of course: this new staging by Melly Still takes any number of artistic gambles. But the orchestra and chorus are the tide upon which Peter Grimes swims, and Hanus and his company made that point more uninhibitedly, and poetically, than I’ve ever heard. The concentrated power that the WNO chorus directed into the auditorium could have stripped the skin from your face. Hanus, meanwhile, found epic breadth and depth in the orchestra. Sullen beauty erupted into sonic violence; string textures rasped and woodwinds shrilled. I don’t think it was Hanus’s nationality alone that prompted thoughts of Janacek.

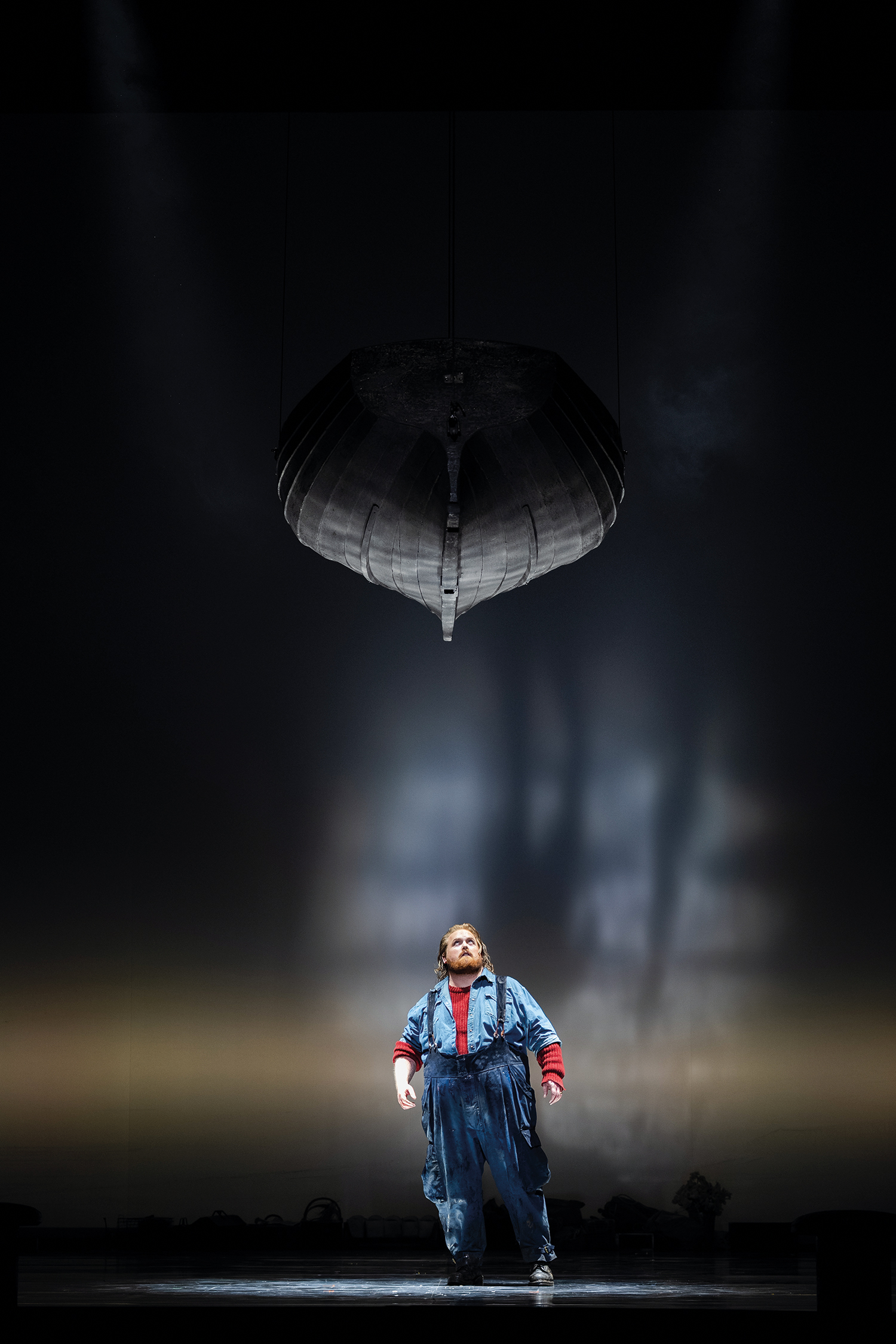

Not a bad foundation, then, for the retelling of a modern myth, and in Still’s production everything unnecessary is pared back. Malcolm Rippeth’s washed-out lighting suggests huge maritime skies, and the few scenic items respect the opera’s setting and work hard as symbols of the characters’ inner life. The tormented Grimes is trapped in a cat’s cradle of ropes. A boat hangs above the stage, turning and tilting with the currents of the drama. As Grimes sings about the Great Bear and Pleiades, it turns black and fills with glistening points of light.

All this austerity serves a purpose, allowing Still to hurl her characters before us as vividly, and as startlingly, as a splash of blood. Still takes a series of increasingly bold decisions about motivation. Ellen Orford (Sally Matthews) is unmistakably in love with Peter (Nicky Spence), he feels the same way about her and the apprentices’ deaths are simply tragic accidents, which have left Grimes distracted with guilt and grief. With those ambiguities resolved, Still focuses with unsparing, compassionate insight on a group of damaged people attempting, in impossible circumstances, to piece together a family and make themselves whole.

So in this Borough it’s never as simple as mob versus outsider. Auntie (Sarah Connolly) and her nieces are presented as potential allies for Grimes, while Balstrode (David Kempster, singing nobly) is worryingly noncommittal. Grimes shows genuine affection for his doomed apprentice; appalled by his own violent impulses, and desperate to master them. Matthews and Spence act as convincingly as they sing – in fact, the vocal characterisation is notable, whether the sadness that drooped from Matthews’s phrases in her ‘Embroidery’ soliloquy or the way that she and Spence, at different times, found the same hushed, floating sonority on the word ‘peace’.

It’s Spence, though, who lifts the show into the stars: a wild-eyed small-town prophet, Lear-like in his final disintegration, with clarity, terror and ecstasy chasing across his face. In a production that stakes everything on the conviction of its performers, Spence goes all in: a career-defining interpretation made all the more potent by the company achievement that surrounds it. This is artistic risk-taking with a devastating pay-off, and there are four more performances in WNO’s cruelly truncated current tour. See it if you can.

There’s also just time to catch English Touring Opera’s big spring production, The Capulets & The Montagues. It’s billed as part of a Shakespeare-themed season, though Bellini’s librettist Felice Romani made a point of basing the work on an Italian (very Italian) reworking. This is the opera in which Berlioz was horrified to see Romeo played by a girl, and in which Juliet rates love a poor third to duty and honour. When it comes to romance, clearly, those buttoned-up Italians have much to learn from us English.

But it’s none the worse for all that and Eloise Lally’s good-looking production depicts the warring families as Italian-American gangsters. Don’t be misled by the company’s name. This touring production has design values as high as anything you’d see at the Coliseum, and the orchestral playing under Alphonse Cemin is very classy indeed. As Romeo and Giulietta, Samantha Price and Jessica Cale are engaging and ardent; two young singers who really know how to caress those long bel canto melodies. The Sheffield audience – a youngish crowd, dressed to kill – seemed thoroughly entertained, and I was, too.

Comments