I have always been sceptical of those passages in the ‘Ancestry’ chapters of biographies that run something like this:

Through his veins coursed the rebellious blood of the Vavasours, blended with a more temperate strain from the Mudge family of Basingstoke.

I have always been sceptical of those passages in the ‘Ancestry’ chapters of biographies that run something like this:

Through his veins coursed the rebellious blood of the Vavasours, blended with a more temperate strain from the Mudge family of Basingstoke.

Those passages seem to claim too much for heredity, and to bear out A. J. P. Taylor’s dictum that snobbery is the occupational disease of historians. But there are some nexuses of talent in allied families that just can’t be denied — the blood cascading down the generations like rills mingling in a grotto. The most flagrant example is the Darwin-Wedgwood-Huxley pedigree. I’d also point to the Literary Longfords, the Amises, père et fils, and Evelyn Waugh, his children and grandchildren.

Those are all examples of inheriting brains like family heirlooms. But with the descendants of the Punch cartoonist and book illustrator, Linley Sambourne, you have to ask: can artistic sensibility also be inherited, aesthetics rather than linguistics or scientific acumen? The father-and-son Holbeins, Cranachs, Cromes, Pissarros and Filippo and Filippino Lippi (Filippino was the illegitimate son of Browning’s friar and a nun), the glass engravers Laurence and Simon Whistler and those stalwarts of The Antiques Road Show, the ceramics experts Henry and John Sandon, suggest the answer may be yes. And then look at Linley Sambourne’s descendants.

At a time when the Albert Memorial was a national laughing-stock and Victoriana in general were derided, Sambourne’s granddaughter, the Countess of Rosse, preserved his house as — what it still is — a time- capsule of Victorian London; and in that cluttered house, with its japonaiserie furniture and blue-and-white china, she, John Betjeman, Nikolaus Pevsner and others founded the Victorian Society in 1957.

Her brother, Oliver Messel, was a leading theatre designer. Her son, Lord Snowdon, is (like Sambourne himself) a master of photography. He designed zoo enclosures and masterminded the investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969, creating a natty uniform for himself. And I hold by what I wrote in this magazine some months ago: that Snowdon’s son, Lord Linley (named for his great-great-grandfather) is the best living designer of furniture.

It was high time that somebody should write a book about Sambourne, and Leonee Ormond has made a first-class job of it — as good as the book on Sambourne’s Punch colleague and friend George Du Maurier which she published all of 41 years ago.

Until recently Ormond was an English literature professor at London University, so she is not a narrow art specialist but conversant with the whole spectrum of Victorian culture, belles lettres as well as beaux arts. She writes very well.

If anybody is tempted to think of Sambourne as a minor fringe figure, he might note that Van Gogh, working in London for the art dealers Goupil, admired his drawings and ‘wrote with pride to his brother of his portfolio of Charles Keene [another Punch artist] and Sambourne’. G. F. Watts told an art critic that he ‘would willingly exchange such ability as he might possess in painting’ for the power to draw a line like Sambourne. And James Whistler called Sambourne ‘the most subtle of the Punch staff’.

Sambourne was born in north London in 1844 — the same year as Gerard Manley Hopkins. His father imported furs from America. The Sambournes and the allied Linleys were involved in the Sheffield steel trade, specifically in making scythes. The Sheffield Linleys were related to the musical Linleys of Bath, two sisters of whom were painted by Gainsborough — one of them eloped with the playwright Sheridan.

Sambourne had little formal training in art, though he attended some life classes. Dürer and Hogarth were his main influences. The death of his father in 1866 probably freed him for the artistic career he longed for. His first cartoon in Punch — a decorated letter ‘T’ — was published in 1867. After that, he was proud to claim, he was rarely out of its pages.

Punch was then as much a national institution as The Times. It had been founded in 1841 with Mark Lemon as editor — the man who first commissioned Sambourne. Thackeray was on the staff, and Dicky Doyle designed the cover that was still in use in my 1940s childhood — Mr Punch with his dog Toby in black and red. The weekly Punch dinner was conducted round the table on which, right up to the sad demise of the magazine, leading staff and contributors carved their initials. (The table is now in the British Library; some time back I was told there were plans to re-create the Victorian offices of Punch there.)

When Sambourne began drawing for the magazine, its three main cartoonists were Tenniel, Du Maurier and Keene. Tenniel was mainly political, and contributed the very influential full-page cartoon each week; Du Maurier was a social satirist; and Keene’s speciality was ‘low life’.

Sambourne’s particular gift, Ormond writes, was for the grotesque, and that is borne out by the illustrations in her book. He was fascinated by women’s fashions, mocking the ‘chignon’ hairstyle and anthropomorphising wasp-waisted women as insects. Lemon’s successor as editor, Shirley Brooks (male) appointed Sambourne to the staff — ‘promoted him to the Punch table’, as convention put it. Sambourne attended his first Punch dinner in 1871.

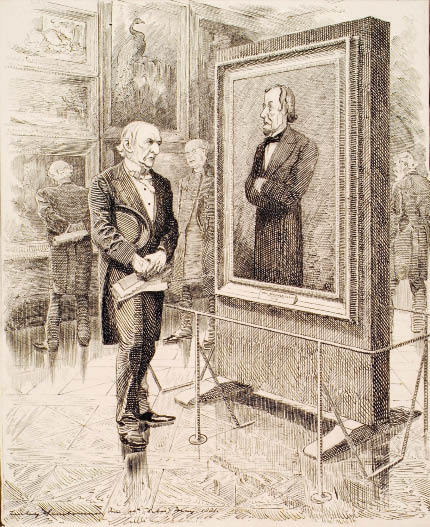

Gladstone and Disraeli were the Punch and Judy of the day. Sambourne portrayed them as octopuses. After Disraeli’s death he made a drawing (rather than a distorted cartoon) of Gladstone staring balefully at a portrait of Disraeli. (It is typical of Ormond’s breadth of art-historical reference that she suggests the picture was perhaps an echo of Paul Delaroche’s ‘Cromwell Gazing at the Body of Charles I’.) In Sambourne’s later days on the magazine, Joseph Chamberlain was often in his sights — the statesman whose deadpan, almost inhuman appearance flummoxed Canon Henry Scott Holland at Gladstone’s funeral in 1898. Luckily for the cartoonists, Chamberlain always wore a monocle and an orchid from his hothouses at Highbury, Birmingham (one cartoon showed him answering ‘an orchid question’) — two emblems that made him instantly recognisable.

In 1874 an aunt died who left Sambourne £650 a year. That enabled him to marry Marion Herapath, daughter of a well-to-do stockbroker. Her father bought them, for £1,000, an 89-year lease of 18 Stafford Terrace, London — the ‘time-capsule’.

Sambourne and his wife both began keeping diaries — a godsend for the biographer. So we learn who his friends were. They included members of the St John’s Wood Clique, which included W. F. Yeames, the painter of ‘And When Did You Last See Your Father?’ and Adolphus (‘Dolly’) Storey, who was at the Sambournes’ wedding. It is regrettable that the article I wrote about the Clique in Apollo in 1964, with the help of Storey’s still living daughter, is still the fullest account of those historical painters — like Sambourne they are just crying out for a monograph. They were a jolly group, given to high jinks.

The Sambournes also moved in more sophisticated circles: in 1884 we find him at a dinner-party with Henry James; in 1886 at another with Whistler; and in 1887 he became a friend of Bret Harte. With Frank Burnand, the long-serving editor of Punch who was a sort of honorary member of the St John’s Wood Clique, Sambourne had a curious love-hate relationship. They were friends and socialised; but Burnand was a tough taskmaster and Sambourne was notoriously dilatory. In 1882 Burnand rebuked him for being ‘more like a spoilt child than a man of business’.

Sambourne aspired to rise in society. It was galling that John Tenniel, Henry Lucy and Francis Carruthers Gould all got knighthoods and he did not; and that none of them was elected a Royal Academician. Sambourne rode in Rotten Row and affected loud tweed suits, rather as Evelyn Waugh did when playing the country gent. Harry Furniss — a Punch cartoonist who was jealous of Sambourne — said he didn’t have a good seat in the saddle. The theatre impresario Sir Squire Bancroft described Sambourne as ‘an amusing little creature, always very horsey in get up’.

Known to his Punch colleagues as ‘Sammy’ or ‘Sambo’, he was the butt of much teasing. At a dinner party somebody pretended to be Stanley of Livingstone fame — Sambourne was completely taken in. Someone else made a list of Sammy’s malapropisms. They included, ‘There was such a silence afterwards that you could have picked up a pin in it’; ‘He was trembling like an aspic’ and ‘I didn’t care for Lady Macbeth in the street-walking scene.’

Sambourne found it difficult to draw from life. From the l880s onwards, he made much use of photography to get the right poses. It is clear that he took an erotic pleasure in photographing nude women, sometimes at Stafford Terrace when Marion was away. In later life he became a rip-roaring dirty old man. Leonee Ormond is level-headed about this. One might ask: ‘Was his photography doing anyone any harm?’ Unfortunately the answer would seem to be yes. He acquired a ‘spy’ camera which took shots at right angles: so he could be aiming it at a tree but was actually photographing nubile schoolgirls in their uniforms. Some of them must have sussed what he was up to and perhaps been a little scared, for Sambourne received a letter from the headmistress of Kensington High School asking him to desist. Today he would probably go on the sex offenders’ register.

Ormond rightly concentrates not on these pervy naughtinesses but on Sambourne’s best work. A certificate for the International Fisheries Exhibition of 1883-84 is regarded as his ‘masterpiece’. His illustrations for Charles Kingsley’s The Water Babies (1885 edition) are also among his most brilliant designs. I read the book as a child (Mrs Doasyouwouldbedoneby sticks in my mind as a pithy summary of most of the Sermon on the Mount) and I remember sensing something sinister in the drawings, and something out-of-bounds in the nude figures depicted. At one stage, Lewis Carroll asked Sambourne to illustrate a book of his poems, Phantasmagoria. The artist’s usual dithering gave him what was perhaps a lucky escape: how trying Carroll could be with an illustrator was recalled by Harry Furniss.

There is a nice human-chain link in that, during her research, Leonee Ormond was helped by Sambourne’s grand-daughter, the late Lady Rosse, who re- called the Friday night ritual of more than 60 years before as Sambourne struggled to complete his Punch cartoon for the next week: ‘A boy would wait for the drawing and speed away as soon as it was completed.’

Sambourne died in 1920. Ronald Searle, another great Punch man, was born that year — as if Fate took off one master to replace him with another, in the manner of a football-match substitute. As I deliver this review I am off to a gallery party to celebrate Searle’s 90th birthday, hoping to meet that survivor of the tragic wreck of Punch.

Comments