In his new book Apostle Tom Bissell has an advantage over writers who go looking for Jesus: he can start with human remains. His frame for this uneven combination of travel and Church history is a series of trips to the alleged tombs of the apostles.

To flesh out 13 ghosts (the 12 disciples and Paul) Bissell mines the gospels, the work of Church historians both early and late, and the Apocrypha. ‘Without the Apocrypha,’ he admits, ‘the 12 apostles would seem even more irrevocably distant.’

The former disciples of Jesus are an elusive bunch. Destroyed or partial texts throw up discrepancies and cases of contested identity, equivocal traditions set in unspecified places and fanciful pasts invented by unreliable chroniclers. The apostle stories that survive are opaque, mysterious and compromised.

Which turns out to be less fun than it sounds. Bissell doesn’t like the Apocrypha — ‘sloppy, repetitive, frequently boring’ — and is forever worrying at the joins (where visible, which is nearly always) between ‘actual Christian history and drowsily velvet curtains of legend’. There isn’t much factual meat on these particular bones, and the historical soup can taste thin. This is a shame, because Bissell is surely correct in his claim that Christianity remains ‘deeply and resonantly interesting’, both culturally and for many of us (including Bissell himself) personally. He points out in his author’s note that he’s approaching this material as a lapsed Catholic and a theological non-specialist.

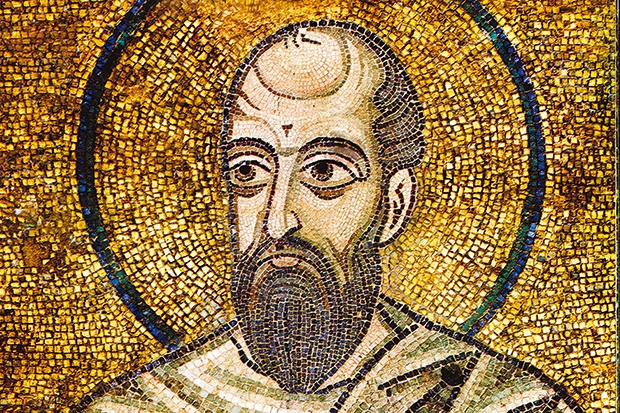

This ought to work as a recommendation, especially in a field where specialists so expertly block out the light. As an outsider Bissell, author of a previous book about computer games, might have been expected to find a refreshingly accessible perspective on the apostles of Jesus and early Church history. Alas, the history and theology of early Christianity have little to do with these slippery followers of Jesus, as the book freely admits. The exception here is Paul, who certainly does influence the development of Christianity, and whose letter to the Romans Bissell calls ‘one of western civilisation’s central documents’.

Theologically Paul is so influential his chapter in Apostle has no room for any travel. Another chapter (of the 12) pushes aside an apostle and is devoted to Christology. Apostle dips its toe into New Testament theology, then falls right in.

Textual discrepancies between the gospels are revisited in detail. Footnotes prop up the pages and the bibliography is extensive, impressive and, well, specialist. Instead of navigating the scholarship Bissell seems determined to fit it all in: surveys of the literature, variations in the Orthodox churches, Hellenism, the languages of India, the Syriac Church, hypostasis and homoiousios.

Any readers who don’t already know their Origen from their Eusebius may wonder where to look. Bissell knows he gets lost — at one point he starts a paragraph ‘For those of you at home’, before yet another digression, this time about Melchizedek (a king who appears in Genesis and the Psalms). I had been hoping not to be at home, trapped in layers of detail, but transported by the excitement of the apostles and Bissell’s travels to find them.

The travel aspect of the book promises some relief, but as a travel writer Bissell’s method is also dependent on research. Apostle adds information about Bernini’s Roman friends, provides the history of the 2005 Kyrgyz Tulip Revolution, and the geology of an individual lake. No book could stand this weight. That’s what the internet is for.

Bissell’s literal journey never really gets started: Jerusalem is ‘disappointing’ and in St Peter’s Square it rains. He gets sick in Chennai and indignant if he can’t use his Visa card. His contemporary travel adventures always seem secondary to ancient questions and confusions, and the research gradually buries an otherwise eloquent travel writer. Bissell nails Russian stoicism in Kyrgyzstan by describing a woman who looks as if she’s ‘spent a large portion of her life being cold indoors’. My personal favourite is the comforting homeliness of Saint Sernin’s Basilica in Toulouse, like a ‘brick cassoulet’.

Much of this material glints brightly, slightly out of reach. Bissell wants to seize on everything, from biblical exposition to the monks of Mount Athos, who forbid even female animals entry — but neither the place nor the idea is explored. Apostle contains too much, and too little.

The German theologian Rudolf Bultmann famously declared the impossibility of discovering the historical Jesus. Imagine the difficulty, then, of going in search of those vaguer characters from the New Testament, the apostles.

In the absence of historical fact, Apostle never quite decides how best to illuminate uncertainty beyond observing that the myths and legends are slightly ridiculous. In the very last line, Bissell reaches the conclusion that stories can be as worthy of attention as any long-lost truth. The reader may have got there before him.

Comments