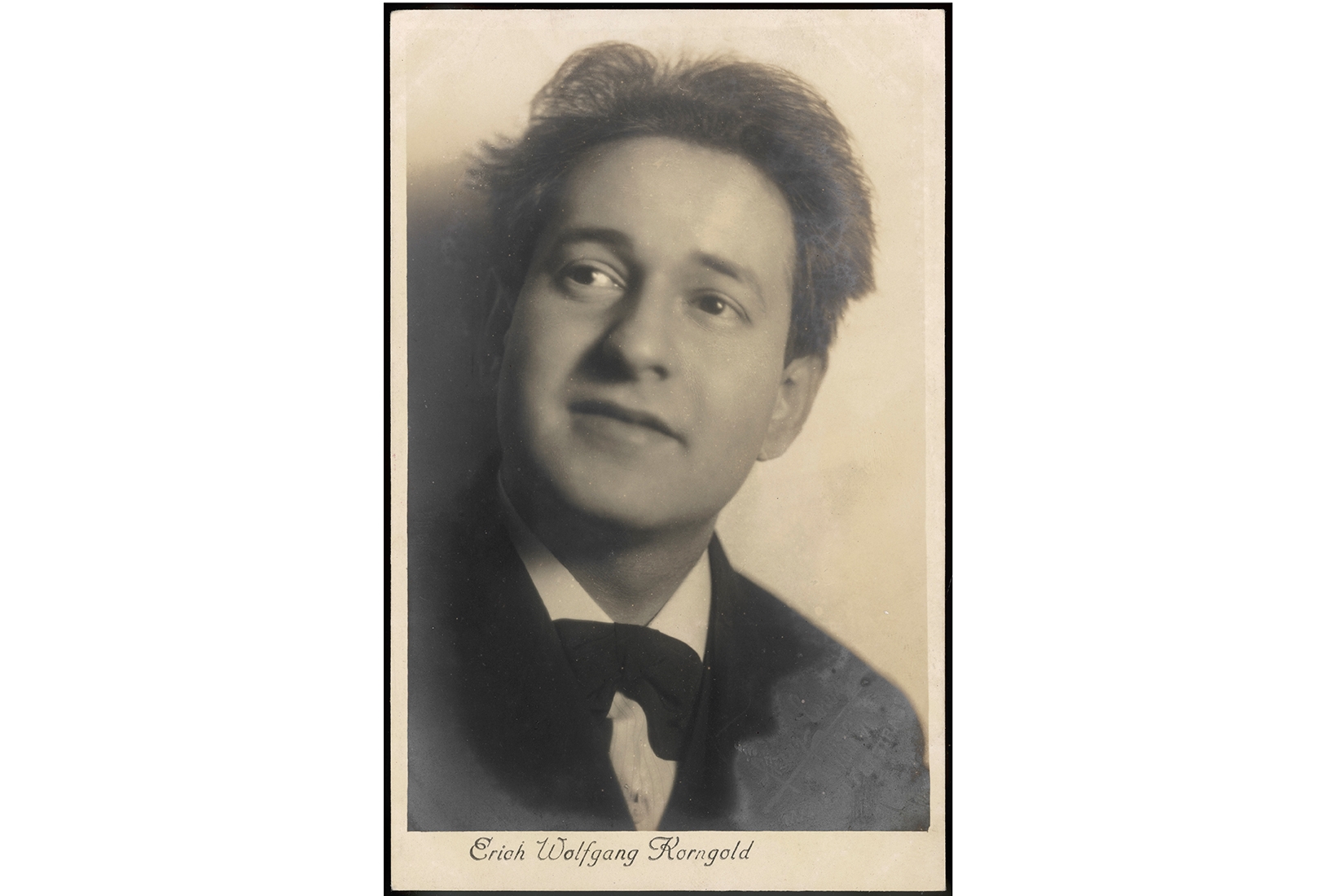

Erich Korngold was what you might call an early adopter. As a child prodigy in Habsburg Vienna, he’d astonished the world: a schoolboy composing orchestral scores that made Elektra sound tame. Jump ahead three decades, and Korngold, in his fashion, was still ahead of the curve. He was one of the first residents of Toluca Lake, North Hollywood, to buy a television. There wasn’t much to watch in 1947, but (according to Korngold’s biographer Brendan Carroll) Jascha Heifetz would drive over anyway from Beverly Hills, and the two exiles — the former protégé of Gustav Mahler, and the greatest violinist on earth — would sit there glued to the live wrestling.

Heifetz’s motives went beyond an enthusiasm for the leotard-clad exploits of Primo Carnera and ‘Gorgeous George’ Wagner. After a decade writing movie scores (a US visa from Warner Bros had saved the life of the Jewish Korngold and his family after the Anschluss), Korngold had recently completed a new Violin Concerto, and Heifetz was out to exercise his droit de seigneur. He premièred the concerto in February 1947. Then it went to New York, and the critics pounced. ‘More corn than gold’ was the crappy little shot that sank the concerto —somebody, give that man a Pulitzer! — and with it Korngold’s postwar career.

‘More corn than gold’ was the crappy little shot that sank Korngold’s violin concerto

US classical critics enjoy enforcing intellectual conformity, and the line in the late 1940s was that romanticism was out and film composers were trash. Korngold died, broken, in 1957 and the concerto faded from view. Then things start to get interesting. Search on Spotify today and you’ll find around 30 recordings. We’re talking credible violinists, too: Renaud Capuçon, Vilde Frang, Arabella Steinbacher. It’s been on Radio 3’s Building a Library, and while its publisher Schott wouldn’t confirm the rumour that it is now the bestselling title in their hire library, ‘it’s certainly one of the most-performed’.

A glance down the discography offers a kaleidoscope of perspectives on a lovely and loveable work: a concerto that sings and sparkles, and whose soaring themes evoke both a lost Europe and blue Pacific vistas. But it’s also a potted history of changing musical perspectives. Naturally, Heifetz tops the list; his 1953 recording was the first, and for years the only one. It’s still compelling. Heifetz’s vibrant, chromium-plated tone, recorded in atmospheric mono on a Studio City sound stage, drops you immediately into the silver screen world of post-war LA.

Heifetz created an instant performance tradition. Itzhak Perlman made one of the first widely available stereo recordings in 1980, and he does not sound wholly comfortable. His conductor, André Previn, was an early champion of the Korngold revival, and Previn’s recordings of the concerto include one in which a gooey-sounding Anne-Sophie Mutter patronises the piece from a great height, as well as its antithesis, a breathtaking performance with Gil Shaham, whose big-hearted verve and lustrous sound make it the zenith of the Hollywood school of Korngold interpretation. It’s still the one I turn to most often.

That came out in 1994. Shortly afterwards, the Heifetz-Hollywood approach received its first prominent challenge from the Canadian violinist Chantal Juillet — paired with concertos by Krenek and Weill as part of Decca’s groundbreaking Entartete Musik series. Decca’s agenda was as urgent as Juillet’s upfront, unsentimental performance: to reclaim Korngold as a European modernist, and the concerto as a document of displacement and loss. More recent interpreters have had to choose their own path between Korngold’s two worlds — to find a balance between the concerto’s swashbuckling fanfares and the underlying melancholy of a piece that Korngold finally dedicated to another Viennese exile, the widowed Alma Mahler-Werfel.

James Ehnes — an artist incapable of making an ugly sound — places the concerto firmly in the line of Beethoven and Brahms: eloquent, noble, heroic in its dignity and breadth. Korngold’s biographer Jessica Duchen pointed me towards a Czech recording from 2009 by Pavel Sporcl, whose resonant recorded sound can’t obscure a strikingly intimate sensibility. A 2020 release from Andrew Haveron, with John Wilson conducting, walks the line with clarity and finesse; two artists with a shared understanding of that tragic, endlessly consequential 20th-century moment when Mitteleuropa found itself stranded on Sunset Boulevard.

But there’s one more that you simply have to hear. In around 2000, the archives threw up a relic — a crackly recording of that very concert in Carnegie Hall in March 1947 when the concerto should by rights have gone global. It’s electric. Heifetz, captured live, plays like a daredevil, and after each movement the audience erupts into spontaneous applause. They love it. A few hours later the New York critics would slap them, and Korngold, firmly back into line. But Korngold’s posthumous comeback from bad joke to cult favourite to 21st-century classic, is evidence that the concert repertoire — supposedly so inflexible — can and does evolve. You heard it here first: the canon is bunk.

Comments