Just before Easter, writing for the Times, I talked to 30 of the 40 Conservative MPs with the most marginal constituencies. My aim was to get a sense of how they think their party should position itself. I explored their opinions on a range of vexed policy areas. Finally I asked whether David Cameron’s leadership was a help or hindrance.

The broad conclusion was that most marginal MPs took a decidedly and sometimes passionately ‘softline’ position on most controversial issues, European ‘interference’ in domestic human rights questions offering the nearest thing to a hardline consensus. And all considered Mr Cameron a plus, though more weakly in the Midlands and North.

I wrote up my results in some detail, my focus being to make a factual report. But my short interviews had been real conversations rather than just box-ticking: they prompted thoughts and observations that fell outside a survey report. What were they?

First, and overwhelmingly, how astonishingly sane and sensible most backbench Tory MPs are. It may be a cliché to remark that it’s only the troubled or the troublemakers who make the news, but it’s true. Talking to me unattributably, few of my interviewees displayed the posturing certainties that characterise the small band of their colleagues who pop up in reports of Tory divisions. Again and again I encountered the agonised doubt that is the mark of a responsible politician: how do you reconcile what the public demand with what it would be realistic to promise?

Three lessons for the party leadership came through strongly. First, that these MPs are fed up with announcements that fall apart or fizzle out or fade away. ‘No more exaggerated promises’ more or less sums it up. My interviewees described their voters as losing confidence in the link between promise and performance. ‘They just don’t believe anything we say any more,’ said a fair few.

Especially this was true on immigration. Almost all my respondents said that on the doorstep they met fairly unconditional hostility to immigration. But they were worried about the practical difficulties in limiting numbers — and very chary indeed about bold promises. Almost to a man and woman they disliked the term ‘crackdown’. They felt they had more to lose through appearing as bigmouths lacking follow-up than appearing timid or soft.

The same was true over the European Convention on Human Rights. The message was clear: ‘Be very sure you’ve worked out how you’re going to stop European interference on human rights grounds, before you strike any more poses on this issue. European meddling irritates our constituents mightily, but so does gesture politics by ministers. If you inflate the language but fail to find any answers, you’re playing into the hands of Ukip. Unless you know the answer, for heaven’s sake don’t talk up the problem.’

There was wariness, too, over bold tax-cutting gestures, unless properly funded. More than a few of the MPs made their case not just in terms of economics but politics: voters really do get the austerity argument, they said; they know the money’s run out; one of their big doubts about Ed Miliband’s Labour party is that it doesn’t seem to. A Conservative-led government should not risk its reputation for being responsible with money.

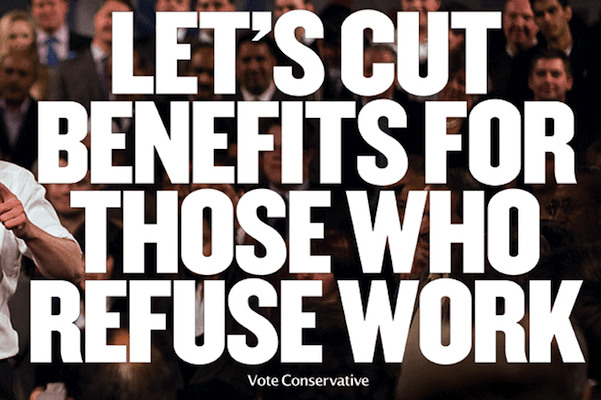

So how about bigger welfare cuts, then? Here my respondents were conscious of what one called a cleft stick. Not one of them (I think) believed their party could simply lay into welfare spending without risking its support. An image of the party as concerned about the poor was important to them, and there was some irritation with MPs in more prosperous seats who can sound careless about welfare. I encountered repeated personal support for Iain Duncan Smith: a sizeable handful told me they were happy to trust the details to him.

All of which brings me to the second general message for the party leadership, for the Tory right, and for those in the party who want a more sympathetic approach to the demands of Ukip. The message is this: ‘We don’t want to look nasty and we don’t want to look mad.’ It would be wrong to say my interviewees were not concerned about Ukip; some were very worried indeed. But they had a wary eye on the floating voters who might float the Liberal Democrats’ or Labour’s way, or stay at home, if the Conservatives acquired a foaming-at-the-mouth appearance. Probably for this reason, a handful of the MPs made the same point to me: that a specific policy on (say) immigration or benefits or overseas aid that might get strong assent from many voters could still hurt the party if it fed into a vaguer and more general impression of unkindness. ‘I may be in favour of cuts, but I don’t like you lot,’ was a possible voter response.

Talking around these issues, I could tell that my respondents occupied a range of positions, from centre-right to centre-left, on the ideological spectrum. They would often have differed over what — ideally — a Tory government should do; but the pressures of maximising their vote tended to herd them in the direction of what some would call moderation, others timidity.

My own view is that a sprinkling of MPs with majorities big enough to leave them free to follow their noses is a healthy thing; scratting around for every vote can cramp you philosophically. My respondents might have agreed, but would beg to point out that if we want to know what’s interesting (or even what’s right) we might indeed consult an MP who needs fear no electoral challenge — but they would be obliged if we would pay a little more attention to them if what we want to know is how to win.

The third message to the leadership is deeply unhelpful. Some of my respondents remarked that Mr Cameron caused them trouble with their party members, while remaining an asset with the ordinary voters. The implication was that Tory activists’ instincts are at odds with much of the general population. What Cameron can do about this, I have not the least idea.

Comments