Maggie’s End

Shaw

Death and the King’s Horseman

Olivier

Here’s an unexpected treat. An angry left-wing play crammed with excellent jokes. Ed Waugh and Trevor Wood’s lively bad-taste satire starts with Margaret Thatcher’s death. A populist New Labour Prime Minister rashly opts to grant her a state funeral which prompts a furious reaction in Labour’s northern heartlands. Former poll-tax rebel Leon Thomas organises a protest march to London intent on disrupting the ceremony and shaming the government. To complicate matters, Leon’s daughter Rosa is a rising Labour MP entangled with the super-smooth Home Secretary (with the slightly-too-clever name Neil Callaghan). In the opening scene Rosa is discovered tupping Callaghan on a parliamentary desk. The news about Thatcher arrives via mobile phone. Both orgasm simultaneously. Gags like these arrive in plentiful swarms. The Mail on Sunday is described as ‘Mein Kampf with pictures’. In a Geordie pub drinkers toast Thatcher’s descent into hell. ‘Hey, she’s probably shut down half the furnaces already.’ But the play aims its sharpest weapons at Labour rather than the Tories. Disenchantment with The Project is now general, universal, ubiquitous. The innocuous line, ‘Trust me, I’m the Home Secretary’ (which scarcely qualifies as a gag), drew such ferocious gusts of hilarity from the audience that we were startled by our own reaction.

This is not a perfect comedy and parts of its construction are extremely clumsy but it has the tang of real emotion, real anger and attitude. Forget the mirror held up to nature: this is the mirror smacked in nature’s chops. The play has a loud-and-clear message for New Labour. The game’s up. And the outlook for Old Labour is none too promising either. Leon’s climactic tirade against the present-day evils faced by radical politicians is, perhaps unwittingly, a useful analysis of the moribund condition of the old left. During the glorious 1980s they fought titans, Reagan, Thatcher, the Coal Board, the poll-tax, neo-Nazis. But look what puny demons remain to them now. DNA data-bases, PFI, student top-up fees, GM foods, CCTV cameras. Only a berk would take to the barricades to oppose these footling projects, some of which, by an apposite coincidence, have fiddly, jingly little abbreviations for names. This play’s run at the Shaw Theatre ends shortly but its stirring blasts of rage and mockery are bound to be heard elsewhere soon.

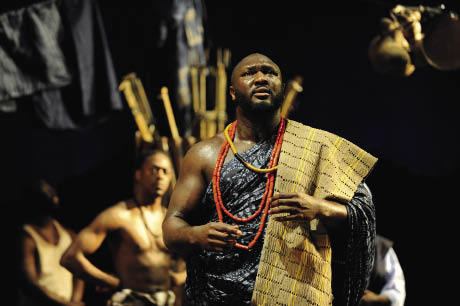

An acclaimed work by a Nobel-prize winning dramatist ought to be well known. Ever heard of Death and the King’s Horseman by Wole Soyinka? This production explains all. The dated setting is a Nigerian backwater in the 1940s where a tribal chieftain has died. His horseman (played with charm and gusto by Nonso Anozie) is honour-bound to kill himself and he takes a bride on the eve of his suicide to cheer his passage into eternity. But, oh dear, those meddling half-wits up at the British residency are determined to interfere and prevent the bloodshed. This critique of imperialism, arriving years too late rather like a UN aid-convoy, is as stodgy as old semolina.

Wole Soyinka has several problems as a playwright. One, he’s not Shakespeare but wants to be. A common failing but he might disguise it better. He takes grand human themes, honour, love, revenge, jealousy, and he sketches them with Shakespeare’s light-and-shade effects: heavyweight scenes featuring high-born characters are interspersed with below-stairs knockabout. Second, he can’t develop a storyline organically and his wordy pageant feels like six set-pieces strung out on a washing-line. Third, he doesn’t appreciate the value of negative characteristics. He seems afraid of creating an out-and-out villain in case we hate him and his characters are chockful of cuddly qualities. They’re wise, gallant, charismatic, long-suffering, smiley, ribald, patient, naughty but they also seem false and unapproachable. Give us a scumbag, Wole, and maybe we’ll love him. His gravest defect is language. These drum-banging peasants sprinkle their speech with quaint allegorical soundbites expressed in faux-Victorian prose which is so unreal it requires translation. ‘My lamp oil is all but drained.’ (I’m going to die.) ‘The cockerel must not be seen without its feathers.’ (Pass my trousers). ‘The arrow does not return to the string.’ (What’s done is done). ‘The sap of the plantain is never dry.’ (Life goes on.) ‘The seven-way crossroads confounds only the stranger.’ (I’ve lost the map).‘My vital flow has intermingled with the promise of future life.’ (Cheers, darling, I’m having a kip.) I didn’t make any of those up and after 160 mins of overworked Wole-cisms I felt rather like those British imperialists. I couldn’t wait to pack up and leave.

Comments