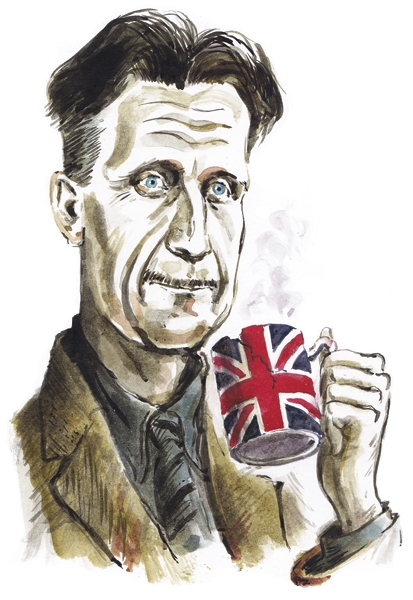

This is the most sensible and systematic interpretation of George Orwell’s books that I have ever read. It generously acknowledges the true stature of the great works — most notably, Animal Farm, Down and Out in Paris and London and The Road to Wigan Pier. It rightly sees the second world war as having brought forth some of Orwell’s finest writing. Yet it does not deify him, and it acknowledges that this strange, drawling, gawky Etonian, who wore common sense like a carapace, was occasionally as capable as the next journalist of writing undiluted tosh.

Witness his claim in an article of 1940 that if he thought a victory in the present war would mean a new lease of life for British imperialism, he would be inclined to ‘side with Russia and Germany’. Even given Orwell’s love of striking attitudes, there is something more than perverse about claiming that you would rather have the world run by the Third Reich and Stalin than by the comparatively benign Indian civil service.

Colls writes:

The truth is, this most famous of political writers did not have consistent — let alone symmetrical — politics, and the strain of trying to be true to the situation as he found it, and true to the natural justice as he believed it in the situation as he found it … produced in him a sort of doublethink almost from the start.

He was therefore a left-wing intellectual who always despised ‘the boiled rabbits of the left’; a public schoolboy who claimed that Eton was ‘bankrupt of ideas’, but many of whose friends, such as Anthony Powell, Richard Rees and Cyril Connolly were Etonians. He disliked religion, but his ideal England was populated by old maids cycling to communion in the autumn mist, and he decreed that his funeral should follow the Prayer Book service.

Although a staunch defender of P.G. Wodehouse during the war, and an essayist who celebrated Dickens, Donald McGill, Billy Bunter and Max Miller, Orwell himself never strikes the reader as having had anything much in the way of a sense of humour. One of Colls’s best observations on The Road to Wigan Pier concerns what Orwell failed to find in the north of England:

He is taken to an afternoon meeting in a Methodist church (‘some kind of men’s association, they call it a Brotherhood’) but shows no interest in this most proletarian of religious movements. Lancashire was the home of football, but there is no football in Orwell. Yorkshire was a stronghold of the Working Men’s Club and Institute, but when he attends their delegate meeting in Barnsley he does not approve of the free beer and sandwiches and thinks they might go fascist. There is no fun, no ambition, no zest, no obscenity and precious little sociability in Orwell’s north.

Well said. I’d go further and add that there was no fun in any of his work, impressive as some of his famous exposures of the Comintern and his denunciations of fascism might have been. Fun isn’t everything, and nor is lyricism — another quality in which Orwell is all but lacking — but their absence makes him a less congenial writer than many of his contemporaries.

Colls writes well about Orwell’s famous ‘list’ which he submitted to the security services in 1949 of Soviet sympathisers who could not be trusted as propagandists to write well about Britain. I do not know if Miliband père was extant as a writer by then, but old J.B. Priestley was. Colls trenchantly sides with Orwell against Priestley’s appalling Russian journey through Stalinist lands — ‘Russia is war-weary, but Priestley has never seen such merriment. Russia is hungry, but his table groans with food.’

Today, many of Orwell’s remarks about the working classes— especially remarks on their smell — make even Swiftian satirists such as Auberon Waugh sound like Pinkos. (‘You cannot have an affection for a man whose breath stinks; habitually stinks, I mean’). Orwell named his poodle Marx as a joke, and then found that he couldn’t ‘look the dog in the face’.

The consistency of the inconsistency, the persistence of the doublethink, is one aspect of the thing which makes Orwell such an abidingly interesting figure and a saint to both left and right. Colls wonders whether, if he had lived, Orwell would have stuck with the Labour party, and decides that he would have because of its ‘organic connection with the working class’.

This section of the book was, to me, the least convincing. It is not that I think Colls is necessarily wrong about Orwell remaining loyal to the people’s party as that it is impossible to imagine him in the era of Thatcher or his namesake, Blair. He seems eternally fixed in his own times: first, as the voice of reason in the 1930s’ clash between totalitarian ideologies, and then, as the chain-smoking creator of those two immortal, but essentially 1940s, dystopias, Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four. His prejudices, such as his anti-Semitism (he believed that there was a disproportionate number of Jews crowding the underground stations during the Blitz) or his dislike of ‘fashionable pansies’ (by which he meant W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and friends) are not so much shocking as very dated.

Colls quotes with approval Bernard Crick’s judgment that Orwell belonged to ‘the awkward squad of dissident Englishmen’. He does seem to have more in common with William Langland, Jonathan Swift and William Cobbett than he does with any strictly political ‘thinker’. Left-wing intellectuals gave him ‘the creeps’, made him ‘sick’, ‘flogged dead horses’ and ‘spouted tripe’. But so do many of the supposedly ‘libertarian’ or ‘Tory’ writers of later decades who invoke Orwell’s name and example.

As Colls says in conclusion: ‘He is a Trust, a Fund and a Memorial Prize.’ This biography’s achievement is to give us back Orwell the writer — neither a saint, nor an infallible sage, but a perverse, intelligent commentator on his time, and also, on occasion, a superb critic.

One of Orwell’s most interesting essays is ‘Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool’. It could be said that Tolstoy was honorary chairman of the awkward squad, and the great Russian’s refusal to see any merit in King Lear is one of his most perverse cries for our attention. Orwell clinically unpicked the theme of Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy — renunciation — and linked it to Tolstoy’s very public renunciation of his money, his aristocratic status and his estates. Orwell is made as uncomfortable by the character of Tolstoy as he is by the character of Gandhi. The essay does not state anything as crude as that Gandhi and Tolstoy were hypocrites, but their very public adoption of poverty creates ‘a sort of doubt’ in the mind of an Old Etonian — who, er, lived the life of a down-and-out in Paris and London, and whose very assumption of a pseudonym suggests more than a hint of the pose.

Comments