Dan Gilgoff on how Barack Obama has narrowed the ‘God gap’

Virtually no political experts saw it coming, but religion was one of the biggest factors in George W. Bush’s 2004 election victory. Bush, who had used evangelical Christian language and championed a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage — a cause pushed by the Christian Right — won 78 per cent of the evangelical vote, a group comprising almost a quarter of the American electorate. Republican presidential candidates had won the evangelical vote ever since Jerry Falwell launched his Moral Majority in the late 1970s, but no presidential candidate on record had ever achieved this level of support.

John Kerry, the first Catholic nominee for president since John F. Kennedy — who won upwards of three quarters of Catholic voters in 1960 — managed to lose the traditionally Democratic Catholic vote to Bush after a handful of American bishops attacked Kerry’s pro-abortion rights stance.

And in Ohio, the state whose 20 electoral votes decided the race, an evangelical-led ballot initiative to ban gay marriage helped give Bush the two per cent margin of victory that sent him back to the White House for four more years.

The so-called God gap of 2004 revealed more than the resurgent political power of old-school evangelicals and Catholics: it testified to the political might of American religion in general. The best indication of whether a voter supported Bush or Kerry wasn’t gender, income level, or union membership — it was frequency of church attendance.

Four years later, it has at times seemed that the Democrats might be the beneficiaries of politicised religion this time around. John McCain has long had an uneasy relationship with the Christian Right. He opposes a constitutional ban on gay marriage, favours federal funding for expanded embryonic stem cell research — a practice many conservative evangelicals and Catholics liken to abortion — and branded Christian Right bosses like Falwell and Pat Robertson ‘agents of intolerance’ during his 2000 run for the White House. Bush wound up beating McCain in that year’s Republican primaries largely by marshalling the Christian Right against him.

This year, McCain won the Republican primaries by relying on moderate Republican voters, leaving Christian Right darlings like Mike Huckabee and Mitt Romney to split the GOP’s evangelical and pro-life base in key primary states like Iowa and Florida. McCain is frequently tone-deaf to evangelical sensitivities, publicly rejecting endorsements by two prominent televangelists last spring because of controversial remarks in their pasts. ‘Very troubling,’ Tony Perkins, one of Washington’s most powerful evangelical activists, said at the time. ‘It would be very difficult to overcome this.’

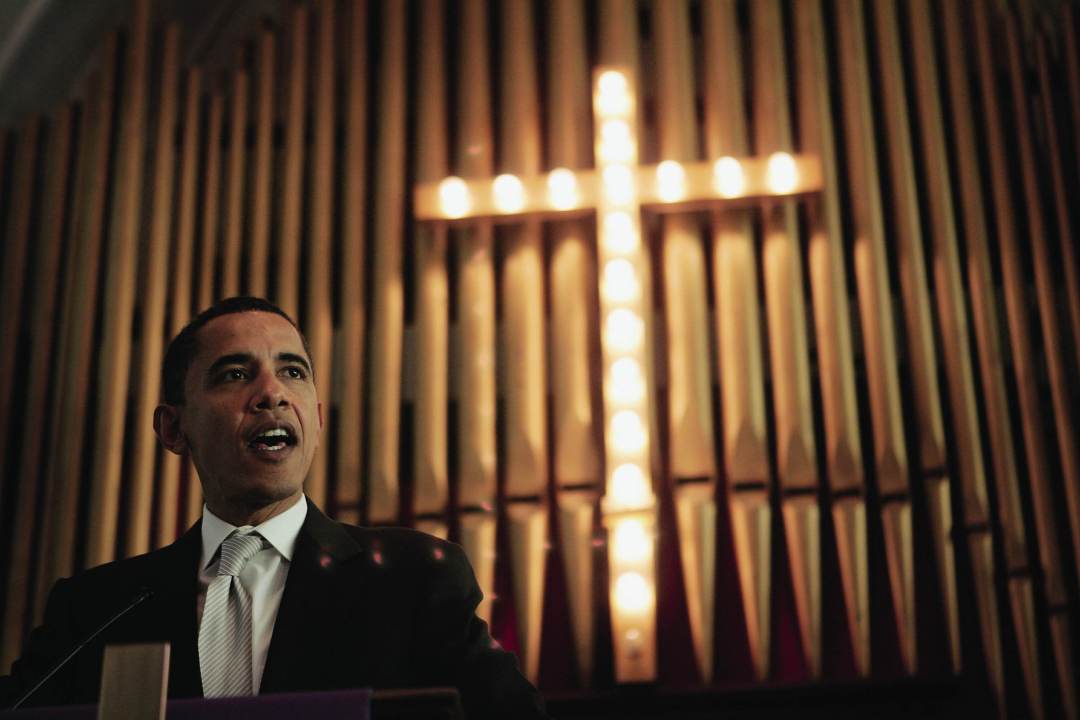

Obama, by contrast, embraces religion as doggedly as John Kerry avoided it. Recalling his days as a church-based community organiser during a visit to a South Carolina mega-church last year, Obama sounded a lot like the born-again Bush: ‘Through that interaction with the church I accepted Jesus Christ in my life.’ The size of the Obama campaign’s professional religious outreach team rivals Bush in 2004. Obama assiduously grants interviews to evangelical news outlets like Christianity Today, even as the McCain camp mostly ignores Christian media. ‘To a lot of people, Senator Obama is an unknown suit that talks the “evangelical talk”,’ says Tom McClusky, chief lobbyist for the Family Research Council, the Christian Right’s strongest advocacy group in Washington. ‘In the general election, Senator Obama speaking “religion” is going to sound more familiar and natural than Senator McCain.’

Yet McCain’s fortunes among the faithful have improved in the last couple of months. The biggest turning-point was his surprise selection of Alaska Governor Sarah Palin as his running mate. A former Pentecostal Christian and fierce opponent of abortion and embryonic stem cell research, Palin electrified Christian Right activists with her story of foregoing abortion to give birth to a son with Down’s syndrome. ‘You know how politics works — you don’t usually get it all,’ crowed Family Research Council Action political chief Connie Mackey on the day McCain announced the Palin pick.

McCain had already won plaudits from evangelicals for his nationally televised performance at Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church a few weeks earlier. (Warren’s Purpose Driven Life has sold more than 30 million copies, and he is regarded as representing the future of American evangelicalism.) Warren asked when a foetus is entitled to human rights protection and McCain said, without missing a beat, ‘at conception’. Obama parried: ‘Answering that question with specificity… is above my pay grade.’ ‘To just say

“I don’t know” on the most divisive issue in America is not a clear enough answer for me,’ Warren, who prides himself on his bipartisanship, groused to me afterward. ‘God planned that child and to abort it would be to short-circuit the purpose.’

In fact, despite McCain’s earlier stumbles on faith-based matters — and Obama’s historic outreach to evangelicals — most polls give McCain an overwhelming advantage among those voters. A late September survey by the Pew Research Center gave him a 70 per cent to 30 per cent lead.

So why are there still plenty of reasons to doubt religion will be the boon to Republicans this November that it was four years ago?

First, hot-button issues like gay marriage have been eclipsed by economic concerns, even among ardent religious conservatives. In 2004, a quarter of all voters cited social issues like gay marriage and abortion as their top concern. This year, according to a new polling analysis by the religion website Beliefnet, only one in eight voters says those issues matter most.

This analysis found that among Christian Right voters, half of whom said social issues were their top priority in 2004, economic issues are now pre-eminent. Among Latino Christians, a fast-growing and traditionally Democratic voting bloc that was nonetheless integral to Bush’s 2004 re-election, just 12 per cent say social issues are their foremost concern, down from nearly 30 per cent in 2004. More than 60 per cent of those voters cite the economy as their main concern.

Second, younger evangelicals are less wedded to the Republican party than their parents. Some younger evangelicals feel the GOP has used their movement, making campaign promises on issues like abortion but not delivering on actual legislation. Others believe that the Christian Right’s narrow agenda, sledgehammer tactics and allegiance to the GOP have tarnished Christianity’s image. ‘There’s an undercurrent of dissatisfaction with the way the older generation has engaged politically and connected their faith with it,’ says David Kinnaman, who leads the Barna Group, America’s main evangelical polling firm. ‘[Born-again Christians] are concerned about who ought to speak for Christ’s followers.’

That helps explain why an analysis last autumn by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found that the share of white evangelicals under 30 identifying as Republicans has fallen 15 percentage points since 2005, to 40 per cent. Most of those voters are migrating to the Independent column, not the Democratic one. But they make it much less likely that McCain will match Bush’s stratospheric evangelical support. One September poll found that while most white evangelicals under 30 back McCain, they are 10 percentage points less supportive than older evangelicals.

Third, although plenty of Christian Right activists are officially supporting McCain, many of their hearts aren’t in it. They 217;re less likely to knock on doors or pick up the phone to promote him than they were for Bush. At a Colorado meeting this summer where dozens of Christian Right heavies decided to coalesce around McCain, they also strategised on how to avoid another McCain-like nominee in future elections. ‘This election is not about McCain,’ says Mat Staver, the evangelical legal advocate who organised the meeting. ‘This is about how we best pursue our core values and advance Christian principles… [McCain] might not represent everything you want in a candidate, but Obama would decimate our values.’

Even after choosing Palin, the McCain campaign has made little contact with religious communities to ratchet up tepid support. McCain’s website includes special pages for ‘Arab Americans for McCain’ and ‘Racing Fans for McCain’, but lacks a page for evangelicals. ‘We put in a request with the McCain campaign and it was never responded to,’ says Richard Cizik, the government affairs chief for the National Association of Evangelicals, the country’s biggest evangelical umbrella group. ‘Many figures in the Republican party have reached out to the campaign stating their concern that the candidate has not reached out to evangelical leaders, but it went nowhere.’

Obama, meanwhile, invited Cizik and two dozen other conservative religious leaders to Chicago for a three-hour powwow last summer. Some hadn’t even met with McCain yet. One attendee, former legal counsel in the Reagan and first Bush White Houses, Douglas Kmiec, was moved to write a pro-Obama book from a Catholic perspective: Can a Catholic Support Him? Asking the Big Question about Barack Obama, published last month.

Will most of 2004’s values voters be so enthusiastic? No way. But Obama has made himself acceptable enough to religious voters to have put culturally conservative states like Ohio and Florida within reach. Small shifts in those states can end up tipping elections. Had John Kerry won the support of as many Ohio churchgoers as the Democratic Senate candidate there in 2006 did — 48 per cent — he’d be running for a second White House term right now. And Barack Obama would not be poised to become his party’s saviour.

Dan Gilgoff is politics editor at Beliefnet.com and author of The Jesus Machine: How James Dobson, Focus on the Family, and Evangelical America are Winning the Culture War.

Comments