Michael Moorcock’s career is indisputably heroic.

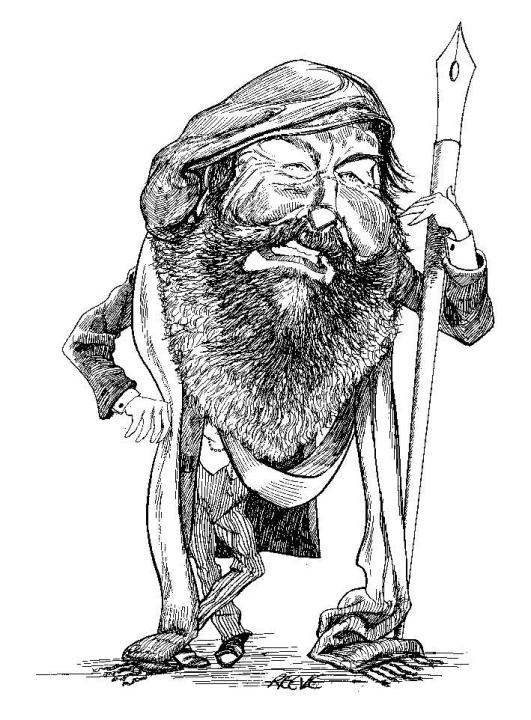

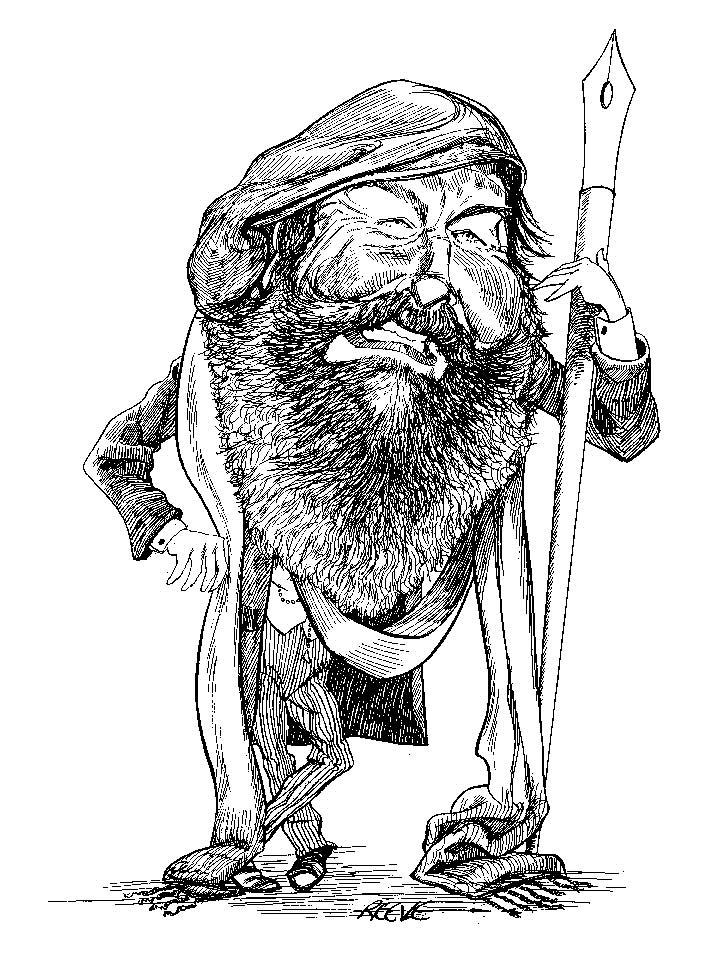

Michael Moorcock’s career is indisputably heroic. At a rate of up to 15,000 words a day, rudimentarily equipped with exercise books, bottles of Quink and a leaky Osmiroid, he has written, among other things, novels by the score, some of which — The Cornelius Quartet, The Colonel Pyat sequence — are among the most ambitious, interesting and funny to have been published since the war. He is not taken as seriously as he might be, though, because most of the rest of his fiction is in the despised and dreaded genre of SF.

In 1968, for example, he published not only two brilliant novels — Behold, The Man (Guardian Fiction Prize) and The Final Programme (the first Cornelius book, written in ten days in 1965, when it was ‘rejected … with disgust and concern for my state of mind … with anger and hatred’), but also four others: The Runestaff, The Ice Schooner, The Black Corridor and The Mad God’s Amulet. The establishment view of him, which he naturally deprecates, has accordingly been that ‘I struggled from the slums of pulp fiction to establish myself in the better-class literary suburbs.’

Among the many sympathetic surprises to be met with in this massive selection of Moorcock’s ‘short non-fiction’ — a mere fraction of half a century’s scribbling (‘a decision was taken to arrange the contents randomly’) — is that he has ‘never been much at ease’ with science fiction. A natural writer, from the age of eight he was steeped in Dickens, Wodehouse and Richmal Crompton’s William books — but it is ‘probably fair to say that I owe my career to Edgar Rice Burroughs’. At 14 Moorcock produced a fanzine called Burroughsania, and by 16 he was a regular contributor to Tarzan Adventures magazine. ‘Between the ages of 17 and 20,’ he recalls, ‘I was able to earn almost any amount of money by writing … and became a fairly dissolute teenager for a while.’ It was only at 20, when he was blacklisted for bolshieness at IPC, that he was ‘forced to turn to science fiction’.

And for all his Herculean contributions to the form, he dismisses it as ‘timid and conservative’, and concedes that it is

almost impossible for the best-intentioned critic to apply his usual standards to a science fiction novel because … he knows, almost before he’s begun reading, that any serious treatment of human affairs will not be attempted.

Quite a lot of the pieces here are about science fiction — his own and others’ — but I think it only polite to ignore them, other than to note his loathing of Star Wars, C. S. Lewis, and most especially J. R. R. Tolkien: in ‘Epic Pooh’ he writes that he is unconvinced of Sauron’s evil, since ‘anyone who hates hobbits can’t be all bad’ .

In other literary fields he is equally scathing about ‘the anaemic, phallo- centric self-advertisements of Notting Hill colons or East Anglian clones’, but full of affectionate enthusiasm for such friends as J. G. Ballard, Angela Carter, Iain Sinclair, Peter Ackroyd and Andrea Dworkin. He writes movingly and at length about Jack Trevor Story (his Richard Savage), and about Mervyn and the Peakes (Moorcock was a teenage friend of Mervyn’s and Maeve’s children), ‘who made me realise it was possible to confront real human issues through the medium of fantasy’, and whom he defends against the cruel ignorance of Quentin Crisp. He has a weakness for Burroughses, and overstates the case for William S., Jr (‘never before has there been purely imaginative writing of such wildness and intelligence’), but writes wittily and perceptively about such elective literary forefathers as Aldous Huxley, H. G. Wells, George Meredith and W. Pett Ridge, author of Mord Em’ly.

There’s a fair deal of wry autobiography. Born in Mitcham, South London, in 1939, he passed his infancy under a hail of V-2s. An only and increasingly large child, he was sent first to a Steiner school, where he acquired ‘a morbid terror of vegetarianism’ and was the first pupil to be expelled, then to a prep school in Norbury, and finally and somewhat inexplicably to a Pitman’s College, which he left at 15, to earn his living by his leaky Osmiroid.

The Final Programme made him a star of the counterculture, and he performed with Hawkwind, and with his own band the Deep Fix: ‘I was a hippy prince. I had an entourage … We did drugs and sex and blew our minds.’ He can remember when LSD was available over the counter at John Bell and Croydon in Wigmore Street, but his ‘true liking’, he confesses, is ‘for killer-narcotics, mainlined’. He acknowledges, though, that they ‘can become a bit of a risk’, and in 1975 he

returned to a rather reactive and overdone sobriety … From being a glamorous bore I turned into a totally dull bore … I gave myself monkish rather than roguish airs.

He is very funny about his stint as a script writer in Hollywood, and interestingly prefers LA to San Francisco. (‘Only Geneva and Amsterdam are neater.’) These days he lives with his American wife in Lost Pines, a liberal enclave of Texas, and deplores the way in which England

seems to be shedding her virtues as fast as she can, celebrating her vices … as class-bound as ever, and in some ways far more repressive than similar Oriental cultures.

Moorcock is elegant and aggressive (‘badly educated people are suspicious of ambiguity’), consistently entertaining, and frequently wise and generous. He is generally sound on religion and politics, despising Blair more than Thatcher, for example. And however heartily one may join him in deploring science fiction, one can only applaud this, written in 1991, on ‘Cyberspace’ (an SF coinage): ‘It is, perhaps, the year 2011 … You float at ease in the centre of a vast library … Brilliantly coloured books radiate towards infinity.’ One applauds the louder when he adds:

Our scientific advances will be merely obscene unless they help the large part of our world’s population emerge from miserable uncertainty and debilitating terror.

John Davey, his editor, is surely right to hail Moorcock as the epitome of ‘the post-War culture ruffian’.

Comments