The other week, when I was shopping in Margate, I saw a number of posters from Boots urging support for its campaign against ‘hygiene poverty’. Barely aware of the term, I looked it up online and was soon presented by claims that much of Britain is gripped by a crisis of personal neglect because of penury. According to the charity In Kind Direct, more than a third of people have either had to cut down on their hygiene essentials or go without them completely due to lack of money. The same charity warns that 43 per cent of parents of primary schoolchildren have had to ‘forgo basic hygiene or cleaning products’ because of the cost.

These figures sound terrifying but do they bear any relationship to the reality of modern life in our country? As someone who lives in Thanet, which has the second highest level of child poverty in the south of England, I am only too aware of real deprivation. It is impossible to walk through parts of Margate without being struck by the atmosphere of decline and despair, from boarded-up shopfronts to dingy bedsits. But this — genuine, everyday poverty — does not make for good adverts.

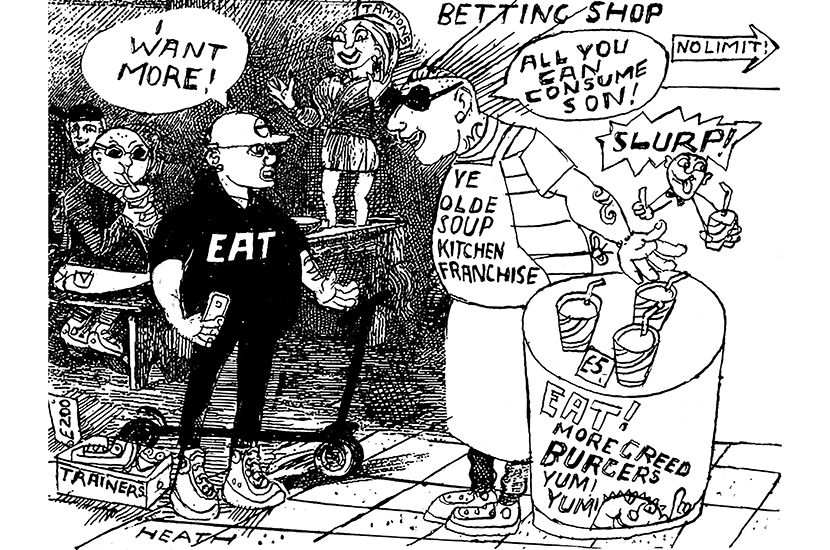

As such, poverty has been rebranded by corporates who like to portray themselves as campaigners against social injustice — in the case of Boots, that not enough people can afford their products. What outrage! This association with anti-poverty is a low-cost, high-profile way to signal corporate virtue — a kind of marketing. Mission statements from Procter & Gamble sound more like the utterances of a democratic socialist movement than a capitalist manufacturer, pledging to ‘create a company and a world where equality and inclusion is [sic] achievable for all’. In the same vein L’Oreal, home of the advertising slogan ‘Because you’re worth it’, now trumpets a social and environmental solidarity programme.

The other difficulty is the tendency towards exaggeration, particularly by pressure groups keen to grab headlines for their latest study. In Kind Direct, for instance, recently reported that more than half of Londoners have been forced to go without essential personal hygiene products because they are unable to afford them: a rather unconvincing assertion about one of the richest cities in the world.

The word ‘poverty’ is now attached to a growing array of new categories, all of them reinforcing the climate of anguish and the demand for more state action. The trade union Unite is campaigning against ‘toilet poverty’ where, according to some reports, ‘tens of thousands of workers in the UK are going without basic access to toilet facilities in the workplace’. The problem is so bad, says Unite, that staff at big branches of high-street banks are being required to urinate in a bucket. Busy (presumably rich) people are routinely referred to as ‘time poor’.

The word is now attached to a growing array of new categories, all reinforcing the climate of anguish

Then there is ‘shoe poverty’ which supposedly afflicts four million children. In February this year, the Daily Mirror reported: ‘Children are having to go to school wearing slippers or Wellington boots due to increasing levels of shoe poverty.’ Footwear hardship is apparently accompanied by ‘clothing poverty’, which, in the opinion of one research group is so serious ‘that thousands of people in the UK have very little or nothing to wear’, which is strange because the cost of clothing has more than halved over the past 30 years.

This theme has almost no end of variations. There is ‘bed poverty’, where 400,000 children do not have their own bed, as well as ‘furniture poverty’, with 14 million households unable to afford at least one essential item of furniture or major appliance. In addition to ‘smartphone poverty’, ‘nappy poverty’ and even ‘holiday poverty’ (in 2011, almost a third of Britons could not afford a week’s holiday, according to the Office for National Statistics), there is ‘digital’ or ‘data poverty’ (both referring to lack of internet access or skills), ‘play poverty’ (little access to playgrounds), ‘book’ or ‘literary’ poverty, where one in eight disadvantaged children have no books of their own — in spite of charity shops selling books for an average of £1.23 each.

This exposes the absurdity of much of this ‘poverty’ hysteria. So often the handwringing claims are not backed up by hard evidence, as can be seen in the case of ‘period poverty’, one of the most popular current causes. A study by the charity Plan International UK says that one in ten girls aged between 14 and 21 ‘have been unable to afford sanitary products’, and one in seven have ‘had to borrow sanitary wear from a friend’. That sounds all too suspicious, given that on Amazon — I stress that this is not my territory — I found a pack of 36 tampons for £4.99, just 14p each.

My doubts were reinforced when I read that the Labour MP Danielle Rowley had told the Commons in July 2018, ‘we know that the average cost of a period in the UK over a year is £500’ — a claim based on a survey by the company VoucherCodesPro of women’s spending habits. Yet as the Channel 4 News FactCheck service pointed out, included in the expenditure on periods were chocolates, sweets, crisps, magazines and DVDs. By Channel 4’s calculations, ‘a more realistic estimate’ is £128 a year or £11 a month, around a quarter of Ms Rowley’s burden.

The use of bogus figures can be found at its most ridiculous in the accusation made by the RAC Foundation that 80 per cent of us live in ‘transport poverty’ because 21 million households spend more than 10 per cent of their disposable incomes on transport, including motoring. The emptiness of this charge can be seen in the RAC’s admission that the richer the household, the higher the expenditure. On its own figures, the lowest-earning quintile spend 9 per cent of their income on transport, compared with the 16 per cent spent by the highest-earning quintile, partly because they buy more expensive cars and spend more money on fuel. In the madhouse of illogicality erected by RAC, the Bentley in the driveway is a badge of poverty.

Poverty matters: the word cannot be redefined by corporates as a marketing tool. Real need is a blight on modern Britain. But the habit of melodramatic overstatement, often for partisan ends, makes solutions harder by creating disillusion and distrust.

Comments