Francis Young has narrated this article for you to listen to.

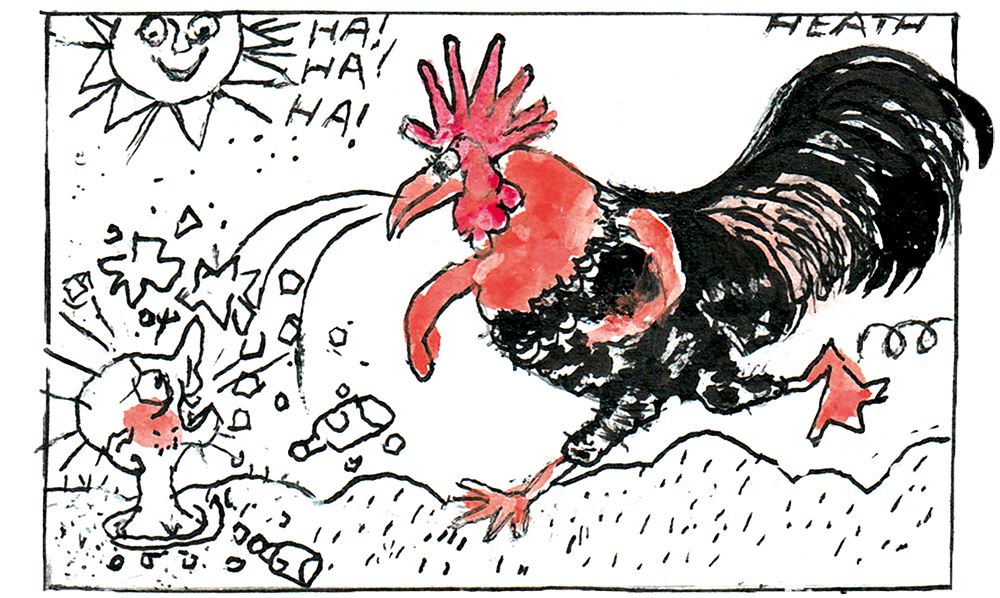

In some countries Shrove Tuesday (the day of merrymaking before the rigours of Lent) developed into a ‘carnival’ that lasted several days, but in England it was only ever a half-day holiday, since it was not an official Church feast day. Apprentices and schoolchildren claimed the right to an afternoon of ‘sport’, and from at least the 15th century the most popular Shrove Tuesday recreation was ‘throwing at cocks’. This was a cruel custom that involved immobilising a cockerel, either by tying its foot to a stake or half burying it in the ground, while bystanders took turns throwing stones, tools and bricks at the cockerel in an attempt to kill it.

The successful killer received the dead bird as a prize, which might account for the custom, since Shrove Tuesday was traditionally the last day before Easter when flesh could be consumed. Sometimes referred to as ‘cock threshing’ or ‘holling at cocks’, the custom varied throughout the country, but invariably ended with the fowl’s demise.

This throwing at cocks was just one of many English blood sports in an era of casual cruelty to animals but it stands apart from others, such as bear-baiting, cockfighting and dogfighting, because it was the first to attract moral objections. As early as the 1730s letters appeared in newspapers deploring the custom, not so much on the grounds of its intrinsic cruelty but for its lack of sportsmanship. After all, the tethered or buried cockerel had no chance to defend itself, and the contest was not one of equals like a cockfight.

Killing and maiming animals when they had no chance to escape offended many people precisely because it was not sport in the way they understood it, but rather mindless violence. The 18th century was hardly an era known for its sympathetic treatment of animals, but by the end of the century magistrates in most areas had outlawed throwing at cocks, even though it was often simply replaced by the scarcely more humane alternative of cockfighting.

By the time the last known instance of throwing at cocks took place at Quainton, Buckinghamshire in 1844, it seemed like a barbaric relic of another world. The RSPCA had been founded in 1824, and already campaigns were under way against cockfighting and dogfighting, as well as the inhumane treatment of horses. The early activists for animal welfare were as much concerned with the deleterious moral effects of casual cruelty on human perpetrators as the fate of the animals themselves. The original objections to throwing at cocks emerged from anxieties about public order and gentility; people with refined manners did not want to run into displays of atavistic brutality.

These were the same concerns that brought an end to public hangings in the mid-Victorian period: public enjoyment of the violent deaths of felons was no longer considered acceptable in a ‘civilised’ nation, even though no mercy was shown towards felons when their executions were hidden from view. The advent of animal welfare was similarly contradictory, and proponents of reform had few concerns about animal sentience or pain. Nevertheless, change must start somewhere and we have public disgust at a Shrove Tuesday custom to thank for the earliest beginnings of animal welfare.

Comments