Laura Gascoigne on how the Venice Biennale is searching for its place in art history

Picture one of the world’s largest private yachts moored at the quayside of the Riva dei Sette Martiri, protected by a metal perimeter fence and a security detail. Now imagine two battered sea freight containers dumped in the shape of a tau cross on the quay just out of spitting distance of the security fencing. One is Roman Abramovich’s 115m superyacht Luna; the other is a Haitian pavilion showing Vodou-inspired sculpture by the Grand Rue Sculptors from the slums of Port-au-Prince.

Welcome to the opening of this year’s Venice Biennale (until 27 November), bigger than ever and more deeply riven with contradictions. The 54th International Exhibition, ILLUMInations, has been selected by art world queen bee Bice Curiger — curator of the Zurich Kunsthaus and editor of Parkett — who, to judge from interviews in the magazine Bice! put out in her honour, follows the postmodern tendency to view art as a visual branch of philosophy. In answer to one question about her soul, she suggested that talk of the soul was ‘rather passé’ — which may explain why her show is a little soulless or, in materialist terminology, flat.

There are a few high points in the Corderie section of the exhibition in the Arsenale. One is Urs Fischer’s monumental copy of Giambologna’s ‘Rape of a Sabine’ in candle wax, with burning wick. Another is James Turrell’s ‘Ganzfeld Piece’, a magical installation of seemingly palpable coloured light. A third is Christian Marclay’s masterpiece of film-splicing, ‘The Clock’: you can tell the time by it, it provides viewing sofas to flop on and it deservedly won this year’s Golden Lion for Best Artist in the Exhibition.

Neither of the last two works, though, are exactly news; both have already been shown in London, ‘The Clock’ twice. Nor is there anything new about the star attraction of the Giardini section of the exhibition, Jacopo Robusti, aka Tintoretto. Curiger has borrowed ‘The Last Supper’, ‘The Stealing of the Body of St Mark’ and ‘The Creation of the Animals’ to hang in the main gallery of the Central Pavilion, overlooked by rows of the stuffed pigeons introduced into the building by Maurizio Cattelan. Tintoretto is an impossible act to follow, and only Fischli and Weiss survive intact with their roomful of concrete elements of drawing and projected moon, ‘Space Number 13’.

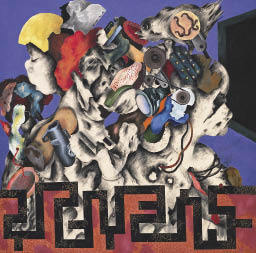

What is Tintoretto doing here? Serving as a spur to experimentation, says Curiger, although his presence could also be seen as a symptom of the Biennale’s growing identity crisis about its place in art history, national history and the international art market. This year Vittorio Sgarbi has used his position as curator of the Italian Pavilion to head a revolt against the international art-critical mafia that decides what qualifies as contemporary art. Defining contemporary art defiantly as ‘what people are making today’, he has handed the selection of his 200 artists to a committee of writers, film directors and thinkers. The result looks a bit like the RA Summer Exhibition, and not in a good way, but with its neon signs reading ‘L’arte non è cosa nostra’ the whole thing could be read as an installation. Several exhibitors have seized the chance to sound off about the state of Italian politics. ‘EX VOTO PROPTER FINEM BERLUSCONIANI PRINCIPATUS. L SERAFIN FECIT AD. MCMXCVII’ is inscribed in Roman capitals beneath one picture. I thought the graffitist who spray-painted ‘BERLUSCONI IN GALERA’ (‘BERLUSCONI IN JAIL’) along the main road to Mestre got his point across more economically.

Graffiti is all the rage in the Giardini, where the pompous colonial pavilions are competing for street cred. ‘ILLUMI-NATIONS’ is scrawled in dripping blue letters across the façade of the Central Pavilion. The Germans have gone one better by spray-painting ‘EGO’ over the first three letters of ‘GERMANIA’ above the entrance to their pavilion, hosting an operatic self-examination by the dying Christoph Schlingensief which has taken this year’s Golden Lion for Best National Participation. But when it comes to self-deprecation, Britain rules.

The British Pavilion has kept up a pristine front while its interior has been completely subverted. For the past three months Mike Nelson, who does all his own dirty work, has been quietly refashioning the inside of the listed building into his usual dusty warren of passages, stairways, bolted doors and abandoned rooms littered with spooky signs of habitation — scattered tools, whirring fans, rusting pieces of industrial machinery, drying photographs, empty bedding. ‘It’s proving hard to get rid of the pavilion,’ he said in April, but with full support from the British Council he has achieved it. They’ve even let him open a hole in the roof to create a courtyard.

The result, ‘I, Imposter’, is less sinister and claustrophobic than earlier installations like ‘The Coral Reef’ (2000), the gallery equivalent of a fairground haunted house. There are squeaking doors but few smells, even from the urinal. The new work is by way of a sentimental salute to the Büyük Valide Han, the dilapidated 17th-century caravanserai where Nelson created an installation for the 2003 Istanbul Biennial and which, partly thanks to the publicity generated, is now being preserved for posterity. Ironically, considering his line of work, Nelson is an apostle of architectural non-intervention. His haunted han feels perfectly at home in Venice, where buildings are allowed to grow old disgracefully without being conserved, as they would be here, to extinction.

This year, the national pavilions steal the show. Among the strongest contributions are the Swiss Thomas Hirschhorn’s ‘Crystal of Resistance’, a glittering maze of tacky consumerism held together with sticky-backed tape; the Japanese Tabaimo’s ‘Teleco-soup’, an elegantly inverted animation of water and clouds; and the Israeli Yael Bartana’s moving trio of films in the Polish Pavilion promoting her doomed utopian vision of returning Jews to Poland.

In the Arsenale, Adrián Villar Rojas deserves notice for filling the Argentine Pavilion with a concrete jungle of surreal columns, and Ayse Erkmen for taking over the Turkish Pavilion with her wonderfully mad construction ‘Plan B’, a water purification unit with extended coloured piping resembling a 3D Tube map designed by Heath Robinson. In these chastened times there is mercifully little sensationalism, although American artists Allora & Calzadilla have come to the Giardini armed with a tank.

As ever, the rare finds are on the fringes. The Iraq Pavilion off Via Garibaldi gets my vote for the most eloquently simple installation on the recurring theme of water: Azad Nanakeli’s three giant taps set into a wall above a cascade of empty plastic water bottles. Iraq also scoops my video award for Adel Abidin’s ‘Consumption of War’, in which two sharp young executives in business suits fight over contracts with strip-light sabres torn from the office ceiling. My runner-up video prize goes to Berry Bickle for her painterly film Ze, and my prize for painterly painting to Misheck Masamvu, both in the Zimbabwean Pavilion in Santa Maria della Pietà.

Yes, even Zimbabwe made it to the ball. The bananas piled against a wall at the preview were not an installation, I was courteously informed, but ‘for refreshment’. How refreshing.

Comments