Every government has its éminence grise. The quiet, ruthless man (or occasional woman) operates in the shadows, only to be eventually outed when the boys and girls in the backroom fall out among themselves or when someone pens a memoir. Think Peter Mandelson, Nick Timothy, Fiona Hill and Dominic Cummings.

The authors of Get In, both lobby journalists, have produced a detailed insider account of the rise of Keir Starmer, as seen through the eyes of those inhabitants of the political underworld whose names rarely surface in the public prints. In this case, the focus is on one alleged strategic genius, a man in his late forties with the memorable name of Morgan McSweeney, referred to throughout by the somewhat sinister moniker of ‘the Irishman’. These days the Irishman is the head of the prime minister’s office and can be seen marching up Downing Street on his way to work. He was not always so visible.

McSweeney, who spent several months working on an Israeli kibbutz, cut his teeth in the byzantine politics of the London borough of Lambeth, then under the rule of Red Ted Knight, and later in Dagenham at a time when the British National Party was on the rise. In each case he concluded that Labour was losing touch with its natural electorate and resolved to do something about it. To this end, he founded an organisation called Labour Together. Despite its anodyne name, it was, say the authors, ‘a conspiracy… Even the name was a lie. Its mission was division.’

Funded partly by the Jewish businessman and pro-Israel lobbyist Sir Trevor Chinn, it first set about destroying the influential online Corbyn fanzine theCanary by persuading advertisers to withdraw. It also fanned the flames of Labour’s alleged anti-Semitism, feeding grossly exaggerated claims to a compliant media. It was duly rewarded with stories such as a lead in the Sunday Times headlined ‘Inside Corbyn’s Hate Factory’. This succeeded all too well. An opinion poll found that the majority of the public was under the impression that 34 per cent of Labour’s 500,000 members faced accusations of anti-Semitism, whereas the real figure was 0.3 per cent – and many of those were unproven.

The authors make some large claims. They credit McSweeney and his friends with persuading Starmer to run for the leadership after Corbyn’s resignation, and then organising his successful campaign. I doubt whether Starmer took much persuading to run. He was obvious leadership material from the moment he entered parliament. Nor did one have to be a strategic genius to foresee his election as leader. Having lost four elections in succession, there were many Labour members of all persuasions who saw Starmer as easily the most credible candidate. Even so, some deft footwork and a high degree of cynicism were required to render him acceptable to the overwhelmingly pro-Corbyn party membership. McSweeney and his associates can certainly take credit for that.

Once Starmer became leader it was a different story:

Having declared himself a friend of Corbyn’s and promising unity, he proceeded to purge the Labour party with unprecedented vigour. Every principle he said he held dear in 2020 has been ritually disavowed.

Corbyn himself, falsely smeared as some sort of racist, was successively suspended from party membership, reinstated but excluded from the parliamentary party, and suspended again before heading off into the political wilderness. A small clique on the Labour national executive also set to work trawling social media in search of dissidents to expel (a number of whom were pro-Palestinian Jews) and purging the list of parliamentary candidates.

These days McSweeney can be seen marching up Downing Street to work. He was not always so visible

Given the mess the Tories were in, it is quite a large claim to suggest, as the authors do, that McSweeney and his associates had much more than a minor impact on the remarkable outcome of the 2024 election. They played a part, to be sure; but the size of the majority was almost entirely due to a quirk of the first-past-the-post electoral system and the fact that for the first time in living memory the Tories had to compete for votes with a credible party to their right. To win almost three times as many seats as the Tories on just 34 per cent of the popular vote suggests that Labour stands on a very narrow beachhead.

Starmer does not come out well from this book. He is variously portrayed as a pawn in the hands of clever manipulators, an HR manager, a passenger on a train driven by others. Like him or loathe him, there is a great deal more to him than that. The authors are so obsessed with process that they sometimes miss the big picture.

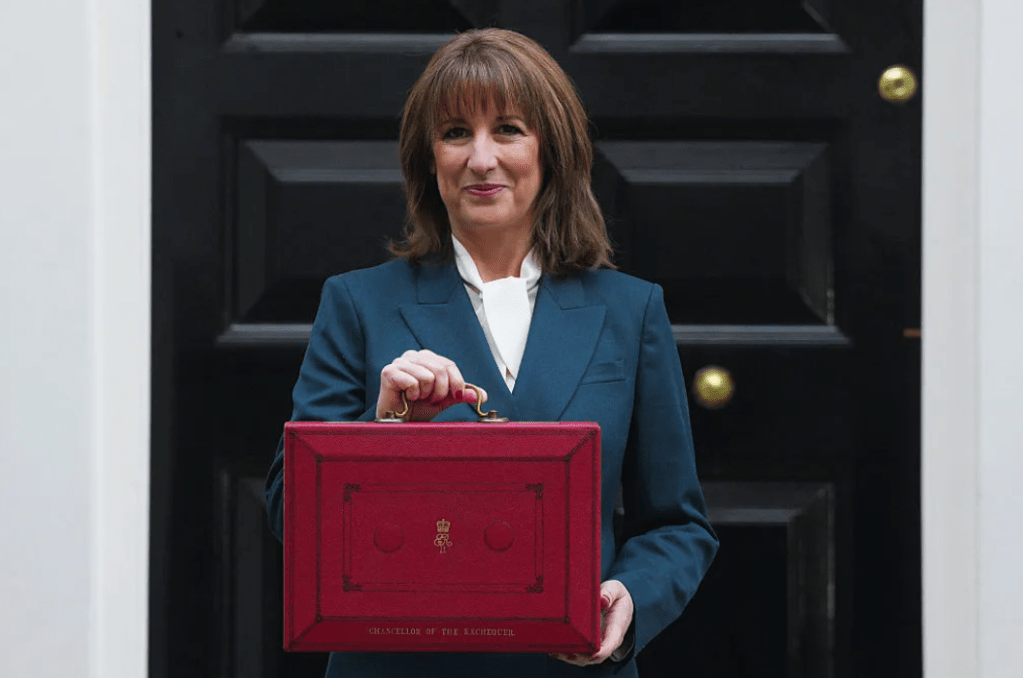

The most glaring omission is a proper discussion of the thinking behind what was arguably the biggest blunder of the pre-election period and one that may haunt this government to the end. In the year before the election, the chancellor Jeremy Hunt slashed national insurance contributions by one third, at huge cost to the exchequer. It was a trap into which Labour fell headlong. Instead of denouncing this as a cynical, irresponsible gimmick and fighting the election on the dire state of the public sector, Starmer and Rachel Reeves pledged not to reinstate Hunt’s cuts. As a result, they have had to resort to some very unpopular measures to try to make up the shortfall. The pit is deep and it may get deeper yet.

One wonders, too, why none of the young master strategists portrayed in this book saw fit to advise their employers that it probably wasn’t a good idea to accept freebies from the multi-millionaire donor Wahid Alli. Not that they should have needed telling.

Heaven knows where all this will lead. As a former senior member of the Blair government remarked to me the other day: ‘Four years from now Nigel Farage could well be prime minister.’

Comments