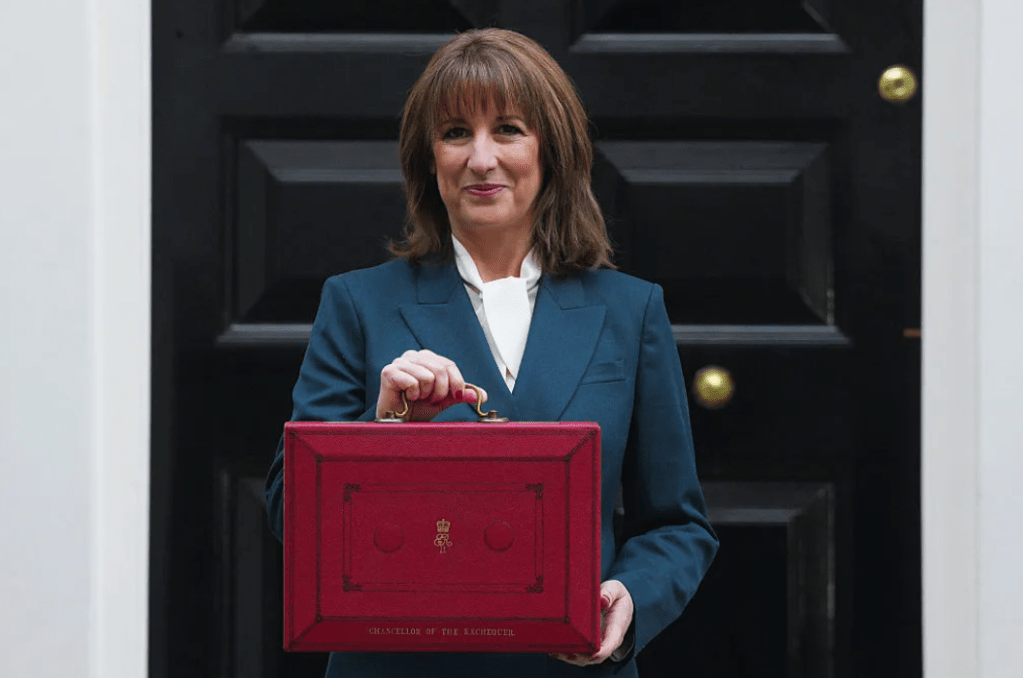

I confess I was lunching at L’Escargot in Greek Street as Rachel Reeves delivered her Budget. My excuse was that I thought I already knew what was in it – but in reality the package was even more anti-business than I feared. My punishment was a risotto too glutinous to finish, but the Chancellor’s 76-minute sermon proved just as indigestible when I tuned in later. Like the wild mushrooms in my dish, the more pungent Budget measures had to be picked out of a blander mass – and I was roused from postprandial torpor by a call from a veteran entrepreneur, regularly quoted here under a variety of disguises, in a fury at one such small-print item.

I warned two weeks ago that Reeves might be eyeing the Enterprise Investment Scheme which attracts capital for private companies but is often gamed by wealthy tax avoiders. Having read the column, I’d like to think, she steered away – but instead attacked ‘investors’ relief’, which allows a lower rate of capital gains tax to be paid on some sales of shares in unlisted companies. The new measure reduces the lifetime limit for ‘IR qualifying disposals’ from £10 million of gains to just £1 million, while raising the applicable CGT rate from 10 to 14 and eventually 18 per cent.

That’s the plainest possible disincentive to serial investors in the sort of early-stage ventures that strive to put the UK at the forefront of technological advance – but more often fail, taking investors’ cash with them, as has just happened to the Oxfordshire-based hypersonic aviation pioneer Reaction Engines. Never mind, say Labour’s spinners, the IR reform will help pay for new classrooms and hospital upgrades. Oh no it won’t, my friends: the background paper says its ‘Exchequer impact’ will be ‘negligible’ all the way to 2030.

So why do it at all? Especially as the paper also claims (though I find this hard to believe since my chum, in one short rant, was able to list several fellow stricken investors) that ‘fewer than 50 individuals are expected to be affected in the 2025-26 tax year’? The answer can only be that Reeves and her ilk start from the conviction that venture capitalists and business angels are not bold risk-takers but incorrigible tax dodgers. As many commentators have already said, the Budget has set a tone for the next five years. For entrepreneurs and their backers, a very long winter is coming.

Pickup penalty

You’re a traditional farmer, proud of helping feed the nation and steward its natural heritage. You’ve always planned to pass the farm enterprise to the next generation, meagre though its income may be. But rich folks buying land nearby for tax reasons have driven the value of yours well above the £1 million threshold that now attracts 20 per cent IHT; and the pension pot you set up with profit from building affordable houses on the edge of the village is about to be dragged into your taxable estate too.

At least you can still enjoy an occasional pheasant shoot, to which you ride in the farm’s Ford Ranger pickup with the dogs in the back. But what’s this, in the Budget’s even smaller print? Double-cab pickups like the Ford have been reclassified as company cars rather than commercial vehicles, attracting (according to What Car?) a whopping increase of up to £9,360 in annual benefit-in-kind tax. And guess what: when Labour backbenchers begin to realise what damage the Chancellor has really done to the prospects of ‘working people’, Downing Street’s red-meat response may well be a proposal to ban game shooting. If you’re tempted to fill the pickup with manure and dump it on the Treasury steps, Mr Farmer, the entrepreneur community will be there to cheer you on.

Out and about

An antidote to the Budget is ‘Two Million Jobs’, a report by Nick Tyrone for the Jobs Foundation, which is a charity founded by the campaigner Matthew Elliott to champion ‘the role of business as a force for good’. Reminiscent of observational work on ‘left-behind’ towns by the former Bank of England economist Andy Haldane, Tyrone visited Sheffield, Loughborough, Hartlepool and rural Pembrokeshire to talk to business owners, employees and activists about how to improve prosperity and life chances.

This grounded approach to policy formulation is, we might guess, in contrast to the method used to address Labour’s own declared objective (which provided Tyrone’s title) of shifting two million people from welfare to work. Picture a conference room full of left-wing researchers: in front of them, name-cards specifying preferred pronouns, and a selection of vegan snacks; scribbled on the whiteboard ‘Employers’ NI’, ‘Workplace regs’ and ‘CGT’ with big red arrows pointing upwards. What’s not in the room is a wall map of Britain showing hot and cold spots with Post-It notes asking ‘Why?’.

Tyrone does not try to cover the whole country but draws powerful conclusions from chosen destinations. Transport infrastructure isn’t good enough; apprenticeship schemes are vital but should be easier to use; funding channels for entrepreneurs are inadequate; green targets are acceptable so long as they’re clear, as are worker-protection laws so long as they don’t ‘stifle risky hires’. Most importantly ‘the climate for business isn’t positive enough; we need to see business people as the “good guys” once again.’ So true, so obvious – but so far from the mindset of the government we’re stuck with.

Wrexham role model

The first place I’d visit in my own quest for positive solutions to decline and stagnation is Wrexham in North Wales, where Ryan Reynolds and Rob McElhenney, the Hollywood actors who attracted global attention by buying the struggling local football club and seeing it promoted to League One, have now doubled down by investing in the historic Wrexham Lager brewery. If Wrexham can go to Las Vegas, as the team now regularly does to celebrate its successes, truly anything is possible.

Comments