Here’s a negotiating gambit that seldom fails. Make a blatantly outrageous demand, and the other side won’t notice they’ve been stitched up in the rest of the agreement. That’s what Brussels did negotiating the Withdrawal Agreement. The backstop got so much attention that Britain’s commitments in the Political Declaration – wrongly thought of as optional extras – were ignored. Boris Johnson has already revealed his focus in the negotiations is to scrap the backstop, and has said that:

‘No country that values its independence and indeed its self-respect could agree to a treaty which signed away our economic independence and self-government as this backstop does. A time-limit is not enough.. the way to the deal goes by way of the abolition of the backstop.’

Exactly the same can be said of the Political Declaration. But the battle over the Withdrawal Agreement and the backstop have created the mistaken impression that signing the agreement means Britain leaves with a deal.

In reality, there is no deal. All we have is the ground plan of a very bad deal outlined in the Political Declaration. The declaration contains many noxious features. Far and away the most significant of these is the EU’s demand that Britain be subject to ECJ rulings and EU extraterritorial jurisdiction under the so-called Ukrainian model of arbitration. And, if somehow Boris’s government cracks the Irish border problem and parliament passes the Withdrawal Agreement, it would be too late to do anything about it.

The Withdrawal Agreement has a binding arbitration procedure. On matters of interpreting a concept or provision of EU law, Article 174 says the arbitration panel shall request from the ECJ a ruling which is binding on the parties. If this jurisdiction only applied to matters covered by the Withdrawal Agreement and was strictly time-limited, it might be tolerable. Astonishingly though, Theresa May’s government conceded the principle of permanent ECJ supervision in the future relationship. Article 174 of the Withdrawal Agreement was rolled forward into paragraph 134 of the Political Declaration and so into any eventual treaty.

This intention to incorporate a treaty provision for the ECJ to interpret and give binding rulings on EU law (and the absence of a symmetrical provision for the interpretation of UK law) implies that Britain accepts the EU’s legal order is superior to Britain’s – even after fully leaving the EU. It is political dynamite.

EU law is not static. Giving the ECJ the supreme role in adjudicating and enforcing the treaty is an invitation to project EU extraterritorial power. In principle, the EU could pass legislation declaring that the UK be treated as an economic dependency in a particular policy area. At the EU’s insistence, a dispute would be referred to the arbitration panel, which would then refer the matter to the ECJ. The ECJ would then respond with a ruling which was binding on the UK confirming the legality of the EU’s extraterritorial power. Britain would be forced to submit to the ECJ’s ruling.

In normal circumstances, this would have been enough to scupper the deal. But the row over the backstop enabled May’s willingness to enshrine the superiority of EU law over parliament to escape scrutiny. If the new government resurrected the Withdrawal Agreement, it would be giving the EU a blank cheque drawn on its sovereignty and negate the entire constitutional purpose of Brexit. We’d have ended up where we started, but with no institutional rights in the making of EU law.

Ukraine was the first country to agree to submit to this 21st century form of EU judicial imperialism, reflecting its desire to be drawn into the EU’s gravitational pull. Georgia and Moldova followed and its use is mooted in EU partnership agreements with other small states. But should Britain really be in the same category as fragile, post-Soviet democracies? Were a solution to be found on the Irish border backstop and the Withdrawal Agreement passed, the full enormity of May’s capitulation would soon become starkly apparent.

By then, it would be impossible to back out. Under the Withdrawal Agreement, the option of no deal no longer exists. The government is required to use its best endeavours and negotiate in good faith a deal conforming to the principles set out in the Political Declaration. The new government would have both hands tied behind its back and its legs shackled. It would then spend an agonising two years negotiating the actual deal – quite possibly in the run-up to the next election – which would make the rows over the Withdrawal Agreement seem like a vicar’s summer tea party.

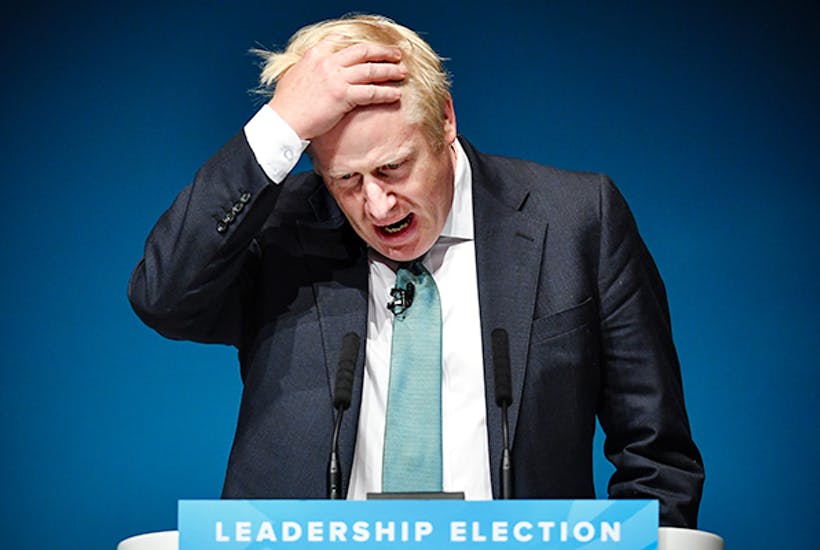

Politics focuses on the immediate and the visible. Like generals who win battles, successful politicians must constantly think about what’s lying beyond the brow of the next hill. Now he’s in No. 10, Boris Johnson is confronted with a decision of enormous consequence: should he seek to renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement in the hope of making it less unacceptable to parliament, or should he use May’s demise as evidence that the British political system will not swallow the Withdrawal Agreement and sink the Political Declaration along with it?

The conventionally minded will try to tinker around with the Withdrawal Agreement. A radical will conclude the game is over and embark on a new, perhaps surprising, course. Make the wrong choice and not only could his premiership could come to an abrupt end but with it, his party and Brexit. Few can envy the burden being placed on Britain’s new prime minister.

Rupert Darwall is the author of Green Tyranny.

Comments