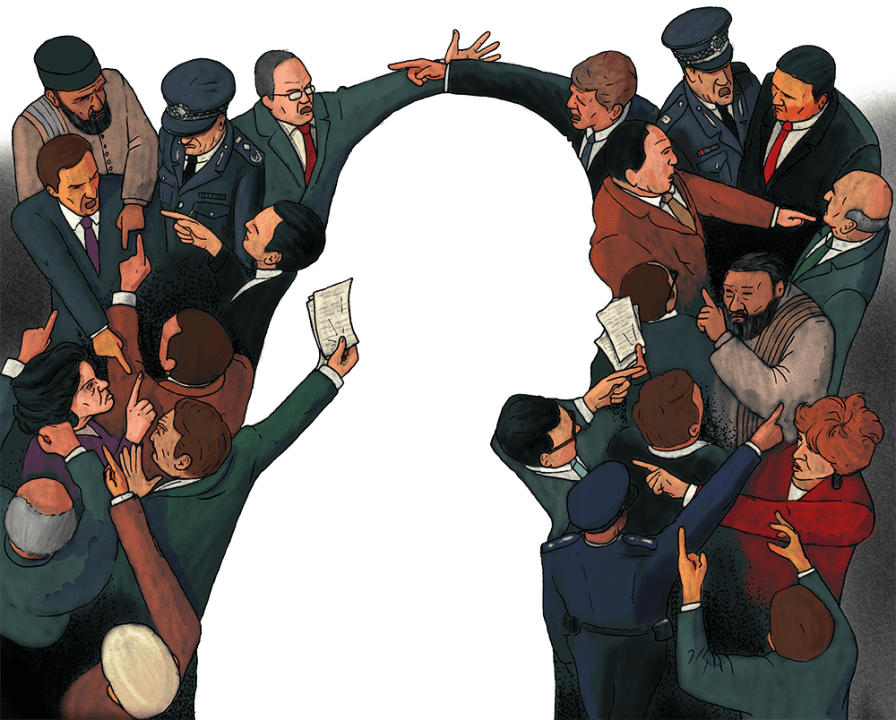

Parliament’s last day before recess is usually a dull affair. A one-line whip allows MPs to return to their constituencies early and the matters for debate are deliberately parochial. When the Commons rose for Easter this week, the government could have expected attention to have been even more desultory than normal, since politicians and the media were focused on the fallout from Donald Trump’s global tariff war. Which is why it is all the more concerning that the Home Office chose that afternoon to slip out the announcement that it was retreating from its commitment to investigate the operations of grooming gangs in five local authorities. Someone must have thought it was a good day to bury bad news.

The government’s new approach to grooming gangs is an invitation to the guilty to evade their day in court

The commitment being watered down was already thin gruel. Rather than establish a national inquiry – as the opposition requested in January – into a scandal that ruined the lives of thousands of young women, the government opted for five discrete local investigations and pledged £5 million to support them. Seeing as the investigative work of GB News reporter Charlie Peters had established that grooming gangs operated in 50 towns and cities across the country, the selection of just five for scrutiny was inadequate. Given that a past inquiry into child sexual abuse in just one local authority, Telford, cost £8 million, the sums allocated for investigation were insultingly paltry.

Initially, though, there was the hope of some rigour being applied to the process. In January, a respected KC, Thomas Crowther, was appointed to draft the framework for the inquiries. This raised the prospect of an attempt to hold local authorities accountable for their failures.

Now even that hope has been extinguished. Crowther has been sidelined and ministers have decided they will oversee the scope of any investigations. Worse, they have given local authorities a veto over any rigorous examination of events.

Following ‘feedback’ from the councils involved – in other words, a concerted pushback against failures being uncovered – local authorities may now adopt a ‘flexible approach’ when it comes to using the money originally earmarked by the Home Office for independent inquiries. Councils can instead opt for ‘more bespoke’ work, such as hosting ‘local victims’ panels’ or undertaking ‘locally led audits of the handling of historical cases’.

The government’s new approach is an invitation to the guilty to evade their day in court. The abuse of young women in so many towns and cities occurred because individuals in local authorities were at best neglectful and at worst involved in criminality. The failure to insist upon properly independent scrutiny is deeply worrying. How can anyone, most of all the victims, have confidence that the institutions which have repeatedly failed will welcome the searching questions required?

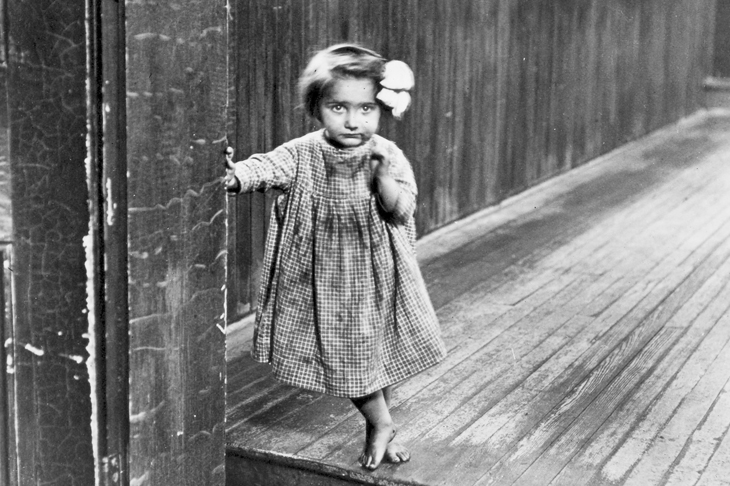

The shadow minister responding to Labour’s retreat, Katie Lam, was admirably forthright in delineating just how much the process has betrayed the victims. The scale and nature of abuse; the targeting of vulnerable girls, often in care settings; the intertwined nature of criminal activity and clannish community cover-ups – all demand a much more thorough approach than the government is ready to offer.

Jess Phillips, the minister responsible for tackling violence against women and girls, has a strong record in supporting victims and campaigning for action against abusers. Her commitment to highlighting past failures, including by Labour local authorities, should be applauded. It is therefore all the more regrettable that her courage has failed her at this moment.

She may believe that some of those most anxious to see these crimes pursued have ignoble motives. That was also the initial reaction of the Times reporter, Andrew Norfolk, who first uncovered the scandal. He was concerned that by laying bare the ethnic and religious backgrounds of the overwhelming majority of abusers, he would give succour to the arguments of right-wing extremists. But he concluded that the truth, however uncomfortable, must be pursued when victims have been marginalised, ignored and forgotten. He also recognised that a failure to discuss difficult questions openly only helps such extremists even more.

It is of course true, as Phillips has argued, that child sexual abuse is a crime which extends far beyond the operation of grooming gangs. It is right that any response to abuse and exploitation takes account of all the ways in which victims can be targeted. That requires more focus, attention and investment to support vulnerable children in care and to encourage fostering, kinship care and adoption.

But in acknowledging these truths, ministers must not hide from others. The sheer number of gang victims, the way in which social services, police and others failed them, the communal cultures which shielded abusers and the attitudes that indulged them all need the determined and unsparing attention of an independent national inquiry. Ministers must think again.

Comments