I keep on my bedside table, where others might place religious texts, Keith Waterhouse’s seminal The Theory and Practice of Lunch. Waterhouse, that magnificent chronicler of Fleet Street’s liquid lunches and disappearing afternoons, understood what modern efficiency cultists cannot: that civilisation is measured not by what we produce but by how elegantly we pause. His gospel preaches that a proper lunch requires ‘two-and-a-half hours of quality time at a quality establishment’, a commandment I try to observe with monastic devotion at least twice a week.

The book’s spine is cracked at the chapter entitled ‘The Lunch Bore’. I have found this section invaluable in identifying – and subsequently avoiding – those melancholy souls who view lunch as mere refuelling rather than the cornerstone of cultural achievement. Waterhouse should be required reading for anyone who has ever uttered the words ‘working breakfast’, ‘grab a quick bite’ or, God forbid, ‘lunch meeting’.

My baptism into hardcore lunch culture came at the age of 23 when I produced the much-missed Steve Wright for Radio 1. Every day, record company pluggers – those silver-tongued evangelists of soon-to-be hits – competed for airtime through the ancient art of gastric seduction. These midday feasts initiated me into a parallel London where lunch wasn’t just sustenance but sport and ritual, all served with a side of gossip.

The expense accounts flowed as freely as the alcohol at now-vanished temples of indulgence: Odette’s in Primrose Hill with its perfectly judged French sophistication; Hiroko’s hushed Japanese sanctuary near Bond Street, where sake appeared without request; and (look away, kids) a place called School Dinners round the back of Baker Street, where grown men dined on nursery teas and spotted dick served by waitresses dressed as schoolgirls who then administered playful canings between courses. Long lunch – with or without the spanking – is the true vice anglais.

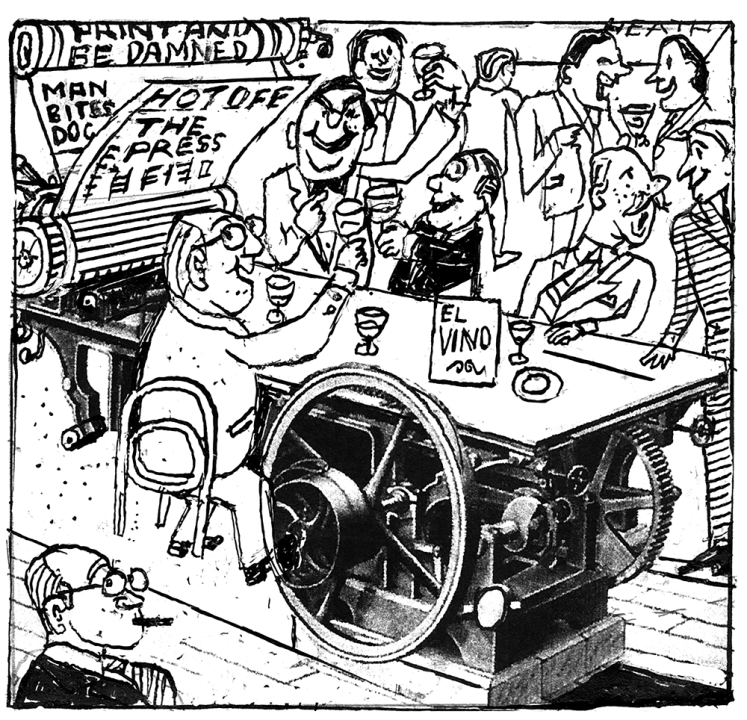

The English have always understood a weekday lunch in a way the rest of the world finds baffling. We approach it with the same mixture of reverence and tactical precision that other nations reserve for military campaigns. A working lunch in London is a paradox wrapped in a napkin: nothing gets done and yet everything gets accomplished. Careers are made or unmade, with decisions climaxing over a double espresso.

Lunch, and I mean a proper two-hour-minimum lunch, is our most elegant rebellion against the tyranny of productivity. It sits, gloriously indolent, in the middle of the day. The working lunch is not, as Americans would have you believe, a dismal affair of keyboards speckled with sandwich crumbs and the faint aroma of desperation. No, a proper London lunch is the last vestige of empire, our final colonial outpost in the grim territory of modern efficiency and tech bros.

A proper two-hour-minimum lunch is our most elegant rebellion against the tyranny of productivity

The true art lies in selecting the correct establishment. Too formal and you’ll never get to the point; too casual and you’ll never be taken seriously. The restaurant must have the correct acoustics – that delicate balance where you can hear your companion but not be overheard by the neighbouring table of influencers. The service should be like good plastic surgery: present but undetectable. And the food must be superb without being so interesting that it becomes a distraction from whatever elaborate fictions you’re swapping with your companion.

After decades of rigorous research (much of it expensed with creative description), I present a smattering of London establishments where lunch achieves its platonic ideal. First, the Arlington: Jeremy King has a pathological inability to create anything less than perfection. After his unceremonious ejection from the Wolseley empire, King has done what all great restaurateurs do: risen again. The Arlington balances grandeur with intimacy, no easy feat. Order the Dover sole, a fish that in lesser hands is merely expensive protein but here becomes a sermon on the virtues of simplicity. King understands that true luxury isn’t gold leaf and champagne fountains but the increasingly rare commodity of being properly looked after over a decent luncheon.

Noble Rot in Soho is my go-to. Especially with visiting Americans who don’t normally drink at lunchtime, until they succumb to the wine list. Noble Rot’s has better character development than most Booker nominees. The food is deceptively simple. The bread alone, with its cultured butter, has been known to reduce hardened CEOs to nostalgic reminiscences about childhood holidays in Normandy and agree to preposterous ideas.

Finally, Sweetings, that glorious anachronism where time stopped somewhere around 1889 and lunch remains what it should be: restorative, slightly intoxicating and governed by rules incomprehensible to outsiders. Standing at the bar with a Black Velvet (champagne and stout, civilisation’s perfect compromise) while waiting for your table, you become part of an unbroken lineage of Great British lunchers. The lack of dinner service tells you everything. Lunch here is not the poor relation of the evening meal but the main event, after which one might as well go home, loosen one’s belt and contemplate the mysteries of digestion.

The long lunch, like foie gras, is ethically questionable but undeniably pleasurable. In a world determined to maximise efficiency at the expense of humanity, these midday repasts stand defiant. Returning, as I always do, to the wisdom of Keith Waterhouse, my only gripe from his rule book is the maxim that ‘no business should take place’. Who is going to pay for it then?

Kenton joined the Spectator’s Edition podcast alongside our restaurant critic Tanya Gold to discuss his piece and defend the proper lunch:

Comments