On 28 January 1986 the Challenger space shuttle exploded shortly after launch, killing all seven crew. What made it worse was that one of the victims, Christa McAuliffe, was a teacher, so of course all the children in her class were watching it live on TV. I remember it well. For the first few seconds after the shuttle blew up, you weren’t quite sure whether or not what you’d just seen was meant to happen: perhaps all those swirls of white vapour were jettisoned boosters or something. Then, you heard the gasps and groans from the crowds standing at the launch site and finally you knew. Up until 9/11 I think it was the most shocking event most of us had ever witnessed on TV.

What I hadn’t been properly aware of, till The Challenger (BBC2, Monday), was the back story. The disaster, it turns out, could easily have been avoided if Nasa had followed the advice of its own engineers. One of the parts on the shuttle — a rubber seal for an O-ring — was vulnerable to cold weather. And on that particular day, the shuttle was launched at a temperature well below the recommended minimum.

But this was more than a routine health and safety oversight. Really, it was manslaughter. Nasa recklessly launched that shuttle because it needed the money. It wanted to demonstrate to the US Treasury that, despite having ostensibly fulfilled its purpose once the moon landings were over, it had a vital new role to play in providing space shuttles as a delivery system for spy and telecommunications satellites.

Nasa was under pressure to prove itself. It had successfully lobbied to have a rival delivery system — a rocket programme being developed by the US Air Force — scrapped. What it now needed to show was that it had the capability to launch space shuttles with clockwork regularity in all conditions. That’s where poor Christa McAuliffe came in. Like the senators who’d gone up on previous missions, her job was to create human interest and to plant in the public’s (i.e., the taxpayer’s) head the idea that Nasa and its space shuttles were worthwhile causes.

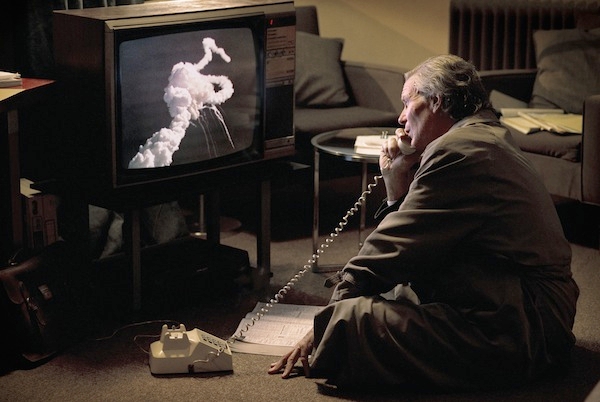

As you may imagine, this scheming was not something Nasa was particularly keen to have come out in the public inquiry into the disaster — the Rogers Commission — ordered by Ronald Reagan. There is the suggestion that the inquiry had been designed to be a whitewash. If so, it made a huge mistake in recruiting to its panel Dr Richard Feynman — bongo-player, Nobel Prize-winning physicist, fearless and inexhaustibly curious seeker-after-truth.

The Challenger was based on an account Feynman wrote with his wife immediately after the inquiry — and just before his death from cancer. In the TV adaptation he was played, no doubt accurately, by William Hurt — all wild hair and sudden flashes of insight, dishevelled, distracted, unworldly, unimpressed by authority, loved by his family, generous to his friends, worshipped by his students and utterly incapable of suffering fools.

For a story reliant on so much arid technical detail, it made surprisingly gripping television, especially in the climactic scene where, like Sherlock Holmes summing up, Feynman demonstrates at the hearing precisely what went wrong. Inserting a section of rubber seal into a glass of ice, he shows that, if subjected to stress below a certain temperature the rubber doesn’t spring back into shape and therefore cannot fulfil its proper safety function.

What particularly interested me about the story, though, were its resonances with another major scandal in which Nasa is currently immersed: the great global warming scare. I do generally try not to mention this topic too often in The Spectator, lest I sound like a one-trick pony. But the comparisons here are just too good to resist, especially with regards to the abuse of the scientific method and the appeal to authority.

The appeal to authority is something one often encounters as a climate sceptic: the idea that because an important-sounding institution such as Nasa declares something to be so, it must be reliably accurate and trustworthy. Yet what the Challenger episode demonstrated is that this ain’t necessarily so: being clever and organised enough to put the first man on the moon is no bar to being so corrupt, greedy and cynical that you’re prepared to send seven innocents to their deaths and then lie through your teeth about it afterwards.

As for the scientific method, Feynman was a scientist of the old school. He wrote: ‘It doesn’t make any difference how beautiful your guess is. It doesn’t make any difference how smart you are, who made the guess, or what his name is. If it disagrees with experiment, it’s wrong. That’s all there is to it.’

Were he alive today, I believe, the good professor would be as scathing towards the charlatans still pushing the tired and long-since-falsified Anthropogenic Global Warming hypothesis as he was towards those bastards responsible for the Challenger disaster.

Comments