Montaigne, who more or less invented the discursive essay, had a method which was highly unmethodical: ‘All arguments are alike fertile to me. I take them upon any trifle . . . Let me begin with that likes me best, for all matters are linked one to another.’ Geoff Dyer could say very much the same thing, and it follows that Zona, though nominally a book about Tarkovsky’s maddening 1979 masterpiece Stalker, goes off in any number of directions. There are other ways of describing a circle than setting out to draw all its tangents, but that is Dyer’s preference.

If the style of approach hasn’t changed, then the cultural context certainly has.

Montaigne could plausibly regard his mind as unexplored territory, but now even the cleverest person’s brain is likely to be closer to a landfill site of dumped and rotting information. In an age of search engines, citations fall like specks of dust rather than points of light. The tendency is towards an unstoppable interconnection unrelated to understanding, either of the self or the other.

The making of an argument would require a drastic sifting of the material, and the establishment of clear criteria of relevance, but that’s exactly what Dyer, perhaps philosophically and certainly temperamentally, resists. He doesn’t set out to peel back his reactions to the film (which on first seeing he admits he found uninvolving) but instead to encrust them further, although the test of a film’s stature is not necessarily how many things it reminds you of.

In Zona there’s a certain amount of analysis of a seductive film-studies sort. Dyer beautifully describes the off-sepia effect of Stalker’s opening sequences, printed in black-and-white but filmed in colour, as ‘a kind of sub-monochrome in which the spectrum has been so compressed it might turn out to be a source of energy, like oil and almost as dark, but with a gold sheen too.’

There’s also background information about the making of the film, the sort of thing you might hope to find in the extra features of a DVD. The script was based on a science-fiction novel, but Tarkovsky refined away the genre elements to leave a more metaphysical journey to a mysterious Zone containing a Room where ultimate wishes can be fulfilled.

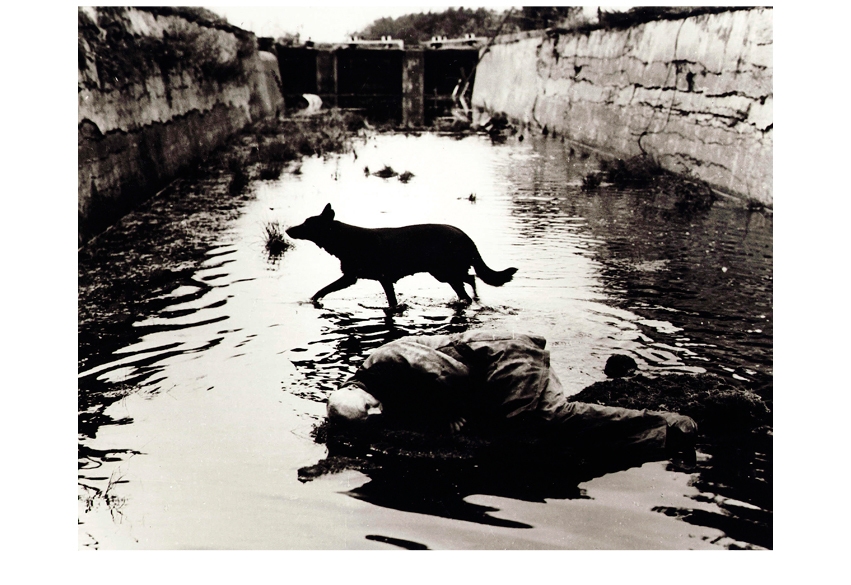

The original terrain for the Zone was a mine in near-desert, until an earthquake ruled out the chosen location in Tajikistan, so that two hydroelectric plants in Estonia were used instead. The wetness of the substituted setting now seems crucial to the working of the film, though the choice may have been even more consequential, if it’s true that chemicals discharged upstream caused fatal cancers in the director, his wife and one of the actors.

In any book that appears under Geoff Dyer’s name, whatever the ostensible subject, there’s likely to be a large accompanying portion of the author. Sometimes it seems as if it’s the subject that’s being served on the side. Every time he sees people drinking in films he wants a drink himself. Mrs Dyer bears a strong resemblance to Natasha McElhone in Steven Soderbergh’s version of Solaris. He loves the idea of quicksand. He has never seen The Wizard of Oz, and never will. He hates the sight of spent matches beside a hob. He won’t allow media vermin (the list includes Jeremy Clarkson and Graham Norton) to infest his house. He would have liked to take part in a three-way with two women, but on the occasions it might have happened he missed out. His wife brought him back a splendid Freitag bag from Berlin, but he lost it one evening in Adelaide. The Dyers often talk about getting a dog, but really they only covet their friends’ lurcher Dotty.

Tarkovsky had a sense of sacred mission that sits oddly alongside this hangdog narcissism, constantly crossing over into self-parody, which may only be a variation on the traditional British reluctance to take anything seriously. He’s pretty serious about Stalker, just the same, saying at one point that its final sequence ‘redeems, makes up for, every pointless bit of gore, every wasted special effect, all the stupidity in every film made before or since.’

He also claims to ‘know’ that if he hadn’t seen the film in his early twenties his responsiveness to the world would have been radically diminished, but this seems rather a stretch epistemologically. If a derelict hydroelectic plant could take the place of desert terrain in the making of Stalker, then another film would surely have emerged to stand in for Stalker in Geoff Dyer’s mental landscape.

Comments