Any bright schoolchild could tell, from a glance at his or her atlas, where the Allies were going to land next, after they had conquered Tunis in 1943: it would have to be Sicily. The deception service persuaded the German highest command that Sicily was only the cover for an attack on southern Greece, after which the Balkans could be rolled up. Hitler was always nervous about the Balkans, from which his armaments industry got the bulk of its chrome and, more importantly, his armed forces half their oil; the trick worked.

Its main plank lay in the floating ashore on the coast of south-west Spain of a body dressed as a major in the Royal Marines, bearing, in a briefcase chained to his belt, letters from General Nye to General Alexander and from Lord Louis Mountbatten to General Eisenhower, from hints in which the Germans were to infer — and did infer — all that the deceivers wanted. The main architect of the plot was Lieutenant-Commander Ewen Montagu, RNVR, working from the cover address of NID 17 (M) at the Admiralty (Naval Intelligence Division). From Montagu’s hitherto unexplored papers, Macintyre has been able to get deep inside the plotting, and expounds a good deal that Montagu suppressed in his celebrated book, The Man Who Never Was, a world bestseller in the early 1950s.

Montagu himself explained 20 years later, in Beyond Top Secret U, one thing he had had to hush up in the earlier book: that we read the Abwehr’s signal traffic between Madrid and Berlin, so that we could follow in detail how the enemy took the bait. Macintyre identifies the actual body, that of Glyndwr Michael, a destitute Welshman who was found dead over Christmas 1942 in an alley near King’s Cross station after eating rat poison — perhaps on purpose, perhaps by accident. His parents were dead, his half-sisters married and out of touch; Montagu persuaded Bentley Purchase, the St Pancras coroner, to release the frozen body to NID, no questions asked.

It was Flight Lieutenant C. C. Cholmondeley, RAF, Montagu’s assistant, who had the original idea; Montagu’s small and cramped staff combined to produce corroborative detail to be carried on the body. At a time of clothing shortage, underclothes were secured from the wardrobe of H. A. L. Fisher, the late warden of New College, Oxford. Getting a major’s battledress was easy; fitting his boots on was harder, but was managed. Sir Bernard Spilsbury, the leading forensic scientist, consulted about what a doctor would make of the cause of death, replied that ‘it would need a pathologist of my experience — and there aren’t any in Spain’ to detect the fraud; but he was wrong. A competent local GP in Huelva reckoned the body had been dead eight to ten days, though it bore in its pocket a bill from the Army & Navy Club only four days old.

Nobody on the German side noticed; partly, Macintyre is sure, because they believed what they wanted to believe. This was exactly the weakness on which the deception service played; in this case, with great success. Hitler reinforced southern Greece, and left Sicily a prey to Eisenhower’s invading armies.

The author has got right inside the minds of the staff who prepared the plot, as well as those who were deceived by it, and has also detected several sub-plots of interest: that Montagu’s brother, Ivor, whom he often saw, was a leading member of the Communist Party of Great Britain; that Mrs Montagu was summoned back from the States by her mother-in-law, who had seen on Ewen’s dressing table a young woman’s photograph with a suspiciously loving inscription (the photograph was on its way into the major’s pocket, to help sustain his cover); that far too many senior officers got involved in drafting Nye’s letter, till they thought of asking Nye to draft it himself.

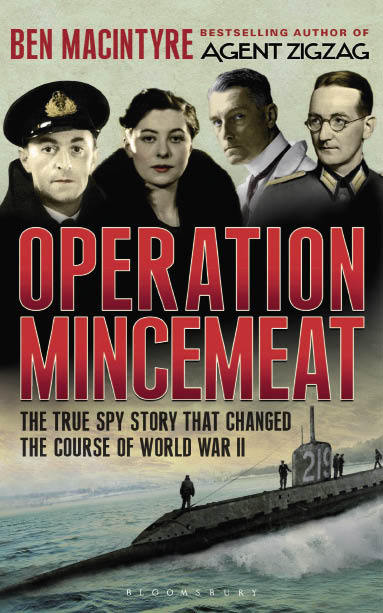

The many and revealing illustrations enhance a chillingly good book.

Comments