‘The House’ in the title of Richard Davenport-Hines’s engaging new book is Christ Church, by any reckoning the grandest of Oxford’s colleges. The place has always been, he notes, akin ‘to an autonomous duchy within a larger federated kingdom’, and thus ‘a separate realm of memory’. Notoriously, its teachers and researchers are referred to not (in the usual Oxford way) as Fellows but as Students. That fact may be thought as good an illustration of its eccentricity as of its charm.

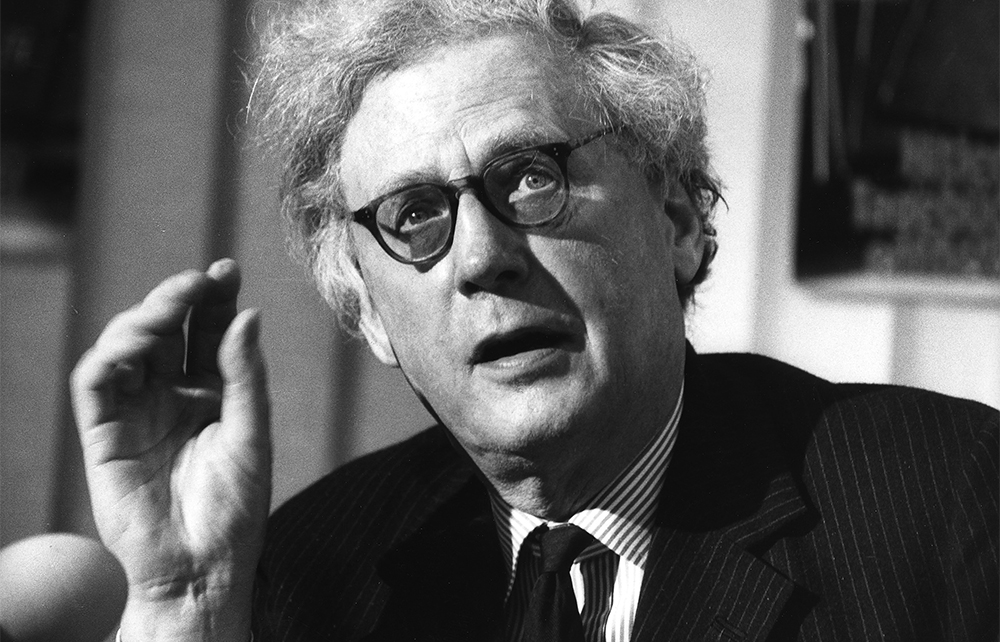

This book isn’t a history of the House, as such, but a more concentrated series of biographical essays about ‘a select and self-regulated group of men who taught modern history’ there in the 19th and 20th centuries. The first part of the book efficiently summarises the mid-Victorian origins of the school of modern history and the self-conceptions of those who first taught the subject to undergraduates. The second consists of eight self-contained portraits of Christ Church historians. Some, such as Hugh Trevor-Roper, are about as well known as any modern historian could be. Others – Roy Harrod – are better known as economists or – Patrick Gordon Walker – as politicians.

There once used to be more books like this one, bearing such titles as Seven Great Balliol Men or Lives of the Great House-masters. In our democratic age, less deferential to the vaunted greatness of Oxford men, it is faintly surprising that such a book found a trade publisher at all. It is a niche product indeed, but Davenport-Hines, serenely unconcerned to demonstrate what publishers call the ‘contemporary relevance’ of his subject, has produced an exemplary work in the genre.

He does not write as an old boy; his degrees were from Cambridge. Nor is his book any sort of memoir:

The closed society of a college enables me to show the interplay of a smallish cast of characters, who… meet in the same common rooms, talk at the same tables, walk in the same quadrangles.

Prolific though they were, Davenport-Hines’s writers were equally distinguished as talkers. What he calls ‘companionate talk’ among men served as a device for the exchange of opinions and the maintenance of customs, but also for careerism. It was, moreover, ‘the medium of their rivalry, resentment and malice too’.

The unpleasantness of dons is not played down. Davenport-Hines gently mocks the hypocrisy of unreformed Oxford in the days when colleges ‘kept a repressive vestige of medieval monasticism by insisting that Fellows make a pretence of asexuality’. Some of the old sexual hang-ups persisted well into the 20th century. J.C. Masterman, we are told, ‘regarded exchanges with someone else of bodily fluids as a threat to his self-possession and to his sense of purpose’. While dons and undergraduates played at sexual ambivalence, we have it on the reliable authority of John Betjeman that ‘there was more talk of homosexuality than action’. The odd episode of rumbly-tumbly came of ‘nothing more complicated than the absence of women’.

Like every other chronicler of the lives (and intrigues) of dons, Davenport-Hines is forced to write sentences that read like summaries of a novel by C.P. Snow: ‘Galbraith was vexed by Trevor-Roper’s championing of Namier’s candidature for the Regius chair in 1948.’ But he is more bothered by the possibility of there being justice to the charge made against Oxford historians that they ‘shrank from abstract thought’. Even more damning was their complacent disregard of the sciences, with some reportedly holding the extraordinary belief that ‘a man who has got a First in Greats could get up science in a fortnight’.

I should have preferred a more traditional sort of history, arranged chronologically rather than by character. But Davenport-Hines allows the patterns to emerge from a dense patchwork of anecdote, quotation and analysis, informed by archival work as well as published memoirs, keeping the editorialising to a minimum. The belief among certain dons that the study of history might ‘provide maxims of statecraft and possibly, too, rational conjecture of things to come’ turns out not to have been entirely fanciful.

And what of the anecdotes? Here, the author delivers the goods on nearly every page. ‘Jumping your full-stops – that is the Oxford accent,’ one don is quoted as saying. ‘Do it well, and you will be able to talk forever.’ Readers of a certain generation will know exactly what this ‘accent’ sounds like. My own favourite anecdote features a little initiation ritual perpetrated by the historian Robin Dundas against a refugee philosopher about to start a teaching job at the college. Was he a Jew, the philosopher was asked. He admitted that he was. But was he a bugger? ‘I’m afraid not,’ he replied. Dundas reassured him: ‘Oh, here again we are quite tolerant.’

Comments