At a Hollywood party in the 1940s, the garrulous socialite Elsa Maxwell spotted Arnold Schoenberg, then teaching music at UCLA, looking miserable. So she pushed him towards the piano with the words: ‘Come on, Professor, give us a tune!’

I couldn’t help thinking of those words on Friday night, when we heard the first Proms performance of a symphony written in 1847 by a professor at the Paris Conservatoire. The Third Symphony of Louise Farrenc is full of well-crafted melodic lines, neatly configured to fit maddeningly predictable textbook chord progressions. It’s delicately orchestrated, but even the feathery flutes of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment couldn’t disguise the professor’s failure to give us a single memorable tune. This is not a popular opinion. ‘Be careful not to upset her fans,’ a distinguished musician warned me after the concert. ‘They’re almost as fierce as the Clara Schumann flash mob.’ He was right: nearly all the references to Farrenc on the internet are gushingly enthusiastic, celebrating not just her music’s technical competence, which is fair enough, but also its ‘distinctive voice’. Really? It’s true that in the scherzo of the Third Symphony you hear a distinctive voice, but unfortunately it’s Mendelssohn’s.

I found only one snippet of mildly qualified praise, from a critic suggesting that Farrenc was a gifted ‘second-tier’ composer. Which raises the question: if she belongs to the second tier, where do we place Hummel and Berwald, both of whom sometimes painted by numbers but could also produce heart-stopping melodies and modulations? And would this symphony have been showcased at the Proms if the composer’s Christian name had been Louis instead of Louise?

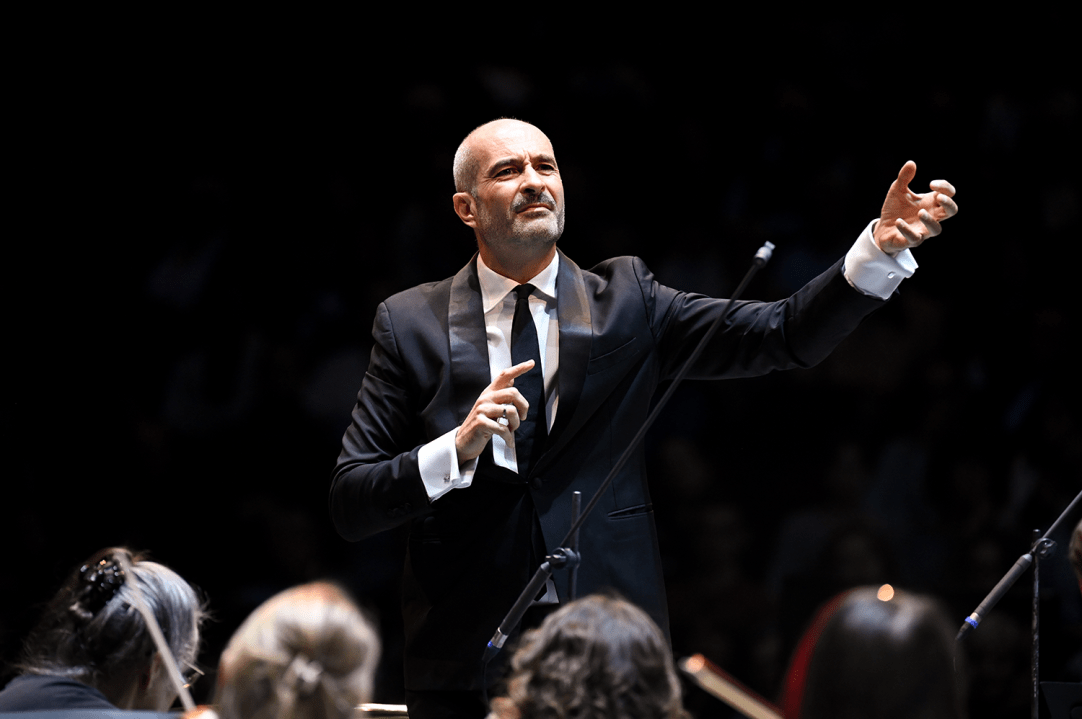

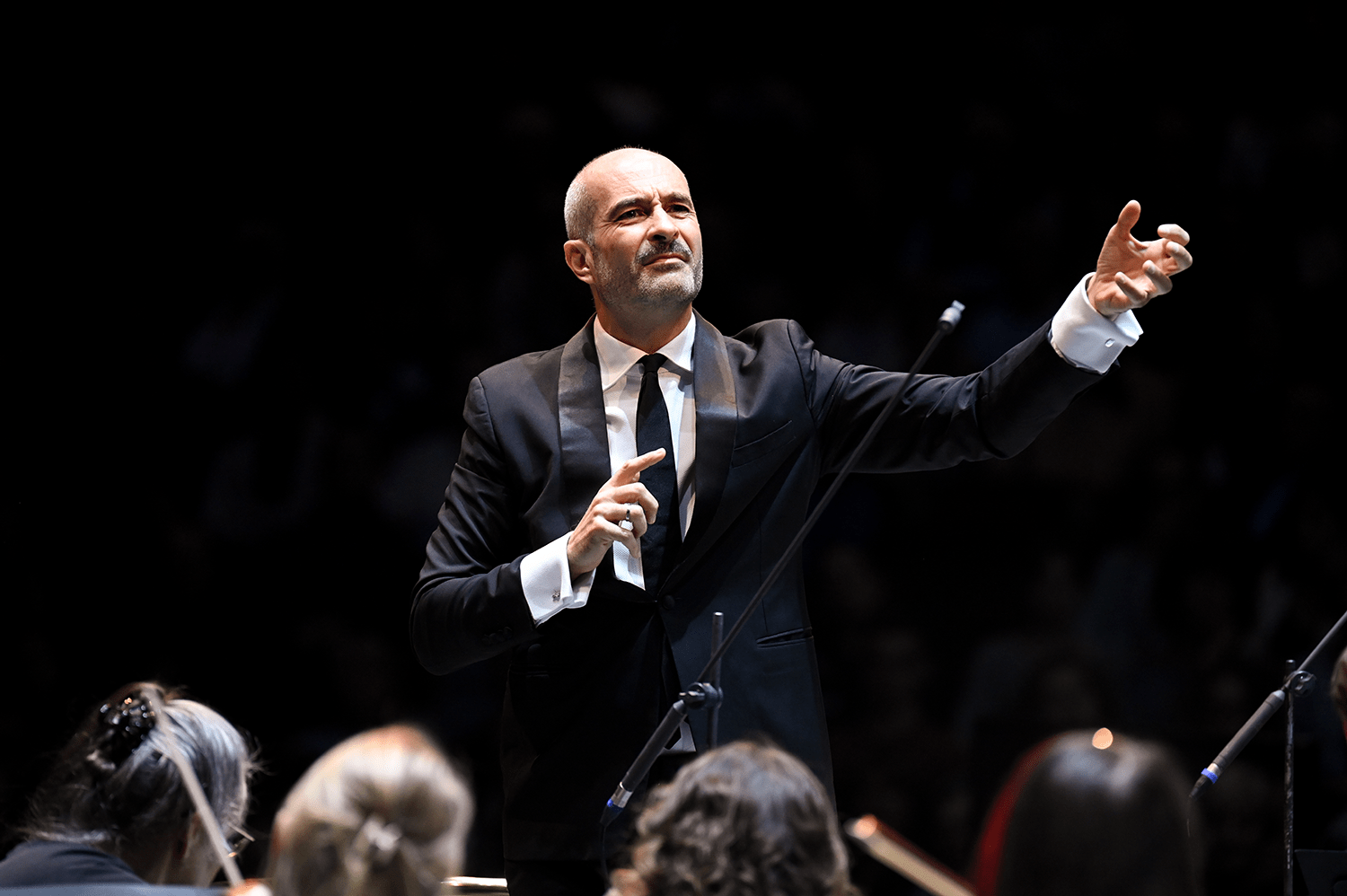

‘Trailblazing’ was the adjective that the BBC chose to describe the Farrenc symphony. It’s hard to think of a more inappropriate description of such resolutely rule-bound music, particularly as after the interval Antonello Manacorda conducted the OAE in the ultimate Third Symphony trailblazer, Beethoven’s Eroica.

The 54-year-old Italian is only now reaching a wider public after recording a Beethoven cycle with the Kammerakademie Potsdam, one of those virtuosic German chamber orchestras that mix modern and period instruments and can blow the roof off with their valveless horns and machine-gun timpani. Its Eroica is razor-sharp and, in the funeral march, achieves a gentle melancholy interrupted by flashes of thunder – an effect that, as the Gramophone critic noted, owed much to the glorious first oboe.

The oboe was one of the reasons Manacorda’s Proms funeral march didn’t reach the standard of Potsdam. It wasn’t the soloist’s fault. The instrument’s statement of the tune plays a big part in establishing the mood of the movement, and it must have been the conductor’s decision – perhaps out of deference to the OAE’s ‘period’ identity – to exaggerate the dotting, making the march sound disconcertingly jaunty. Matters weren’t helped when Manacorda stepped too hard on the gas for the beatific central section; it may be ‘a sudden ray of sunshine in a dark sky’, to quote George Grove, but this verged on the jubilant, as if the mourners were happy that the hero was dead. The thunder, compared to the Potsdam recording, was disappointingly muted.

But there were also thrills. The timpanist’s hard sticks ripped through the Albert Hall’s mushy acoustic. Although the natural horns slipped from time to time, as they do in live performances, they gave us a wonderful blast of the hunting field in the scherzo. The theme of the finale was rollicking and carefree, and if there was a feeling of drift half way through the movement we should blame Beethoven: after the slow variation he takes so long building up the grandeur that the explosive coda is too little, too late.

At the Barbican on Sunday, Sir Antonio Pappano demonstrated his charismatic command over the London Symphony Orchestra. The main item was another Third Symphony, by Saint-Saëns, in a performance that didn’t live up to its popular title of ‘Organ Symphony’. There was an organ, of course, played by the great Anna Lapwood, but it was a modest instrument that couldn’t compete with the LSO’s ferocious brass.

Pappano builds his sound from the bottom up; his dark textures and bursts of operatic melodrama were perfect for Berlioz’s Roman Carnival Overture, but in the Saint-Saëns they overwhelmed not just the organ but also the loveliest thing in the score, the torrent of arpeggios from the orchestral piano.

That didn’t happen to Yuja Wang in Rachmaninov’s First Piano Concerto. She found the muscle to match the sweep of Pappano’s cinematic accompaniment, and in the slow movement her twists of rubato summoned the restless spirit of Scriabin. What a deeply probing musician she is, and how deplorable that so many critics feel obliged to mention her skimpy dresses and four-inch heels. So I won’t. But I loved the sunglasses.

Comments