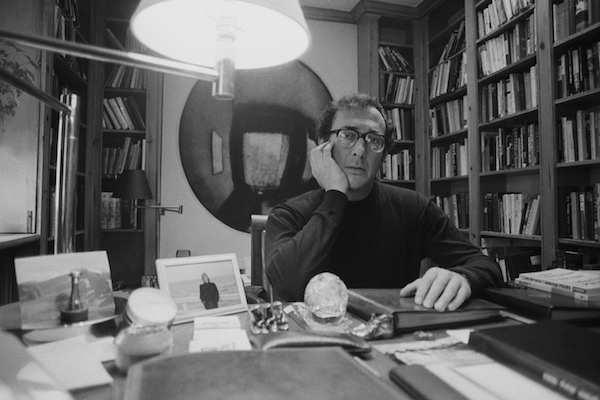

On a warm summer evening in 1986, the crème-de-la-crème of London’s literary establishment met at Antonia Fraser’s house in Holland Park to discuss how they could bring about the downfall of Margaret Thatcher. Among their number were Harold Pinter, Ian McEwan, John Mortimer, David Hare, Margaret Drabble, Michael Holroyd, Angela Carter and Salman Rushdie, who referred to Thatcher in The Satanic Verses as ‘Mrs Torture’. With characteristic lack of modesty, they called themselves the 20 June Group — a reference to the plot to assassinate Hitler that was hatched on 20 July 1944.

‘We have a precise agenda and we’re going to meet again and again until they break all the windows and drag us out,’ said Pinter.

Several commentators have pointed out that one of the reasons Thatcher was able to win so many political -battles is because she was blessed with particularly feeble enemies. They’re thinking of Arthur Scargill, General Galtieri and Michael Foot, but these literary giants deserve a mention. They claimed to be of the left and thought of themselves as heroic dissidents, but their objection to the Iron Lady, in essence, was that she threatened the cultural hegemony of Britain’s upper-middle-class elite by unleashing the forces of social mobility. This was obvious from the language that a member of this set, the opera director Jonathan Miller, used to describe her. According to Miller, Britain’s first woman prime minister was ‘loathsome, repulsive in almost every way’. He objected to her ‘odious suburban gentility and sentimental, saccharine patriotism catering to the worst elements of commuter idiocy’. In other words, he didn’t like her because she was a grammar school girl — a ‘Northern chemist’.

Such snobbery was unlikely to turn the mass of the British people against her, yet it was equally apparent in Paradise Postponed, John Mortimer’s 11-part jeremiad against Thatcherism, broadcast in 1986. The central character, the object of all Mortimer’s scorn, was Leslie Titmuss, a farm labourer’s son who becomes a right-wing Conservative MP. Mortimer’s snobbery was so undisguised that even the New York Times objected that the ‘lower orders’ were portrayed as either forelock–tugging peasants or ruthless Tories. The message was clear: Margaret Thatcher should never have attempted to jump the counter of her father’s shop.

Mortimer and others seemed to grasp that the 1945–79 consensus, with its uneasy truce between trade unionists on the one hand and the boss class on the other, depended upon every-one knowing their place. Whatever the shortcomings of the Tory old guard, at least they shared the metropolitan left’s disdain for ‘barrow boy’ City traders and ‘vulgar’ businessmen. Provided the English class system remained intact, the post-war settlement could be preserved.

The extraordinary thing is that these Labour party stalwarts saw this as an argument in favour of Butskellism, rather than an argument against. The existence of ‘the establishment’ — first identified in the pages of this magazine in 1955 — wasn’t merely an acceptable cost; it was a positive virtue. This was clear from the hostility exhibited in various novels and plays of the period towards anyone who showed the faintest sign of upward social mobility. Exhibit A is John Self, the monstrous protagonist of Martin Amis’s novel Money, but there are countless examples. The working-class boy made good, in some ‘ghastly’ 1980s profession like estate agency, became the object of near-universal cultural derision. As far as the intelligentsia were concerned, the moneyed ‘oik’ was the unacceptable face of Thatcherism.

This analysis of Thatcher’s cultural critics was fairly well-rehearsed at the time. Indeed, I was in the foothills of my career as a conservative pundit and often trotted it out myself. But what made the 20 June Group particularly welcome is that it laid bare the naked self-interest behind the sanctimonious arguments of her high-minded opponents. Of course they weren’t in favour of the principle of meritocracy! Most of them were the beneficiaries of hundreds of years of inherited privilege. This was made explicit by the venue they chose to hold their first meeting in — a five-storey Georgian house in one of west London’s most desirable squares, belonging to the daughter of an earl. The disconnect between the revolutionary rhetoric and the pampered reality was almost comic.

One day, someone will write a comic novel about Thatcher’s Britain where the ‘satire’ isn’t confined to young men who work in advertising and drive Porsches. Perhaps I’ll do it myself.

Comments