In travelling to Bishkek, I was heading for the hills. I had not expected to be marking the 80th anniversary of victory in Europe there. But thanks to our leader, Alexandra Tolstoy, who has high standing with the authorities in Kyrgyzstan, we found ourselves in honoured places beside the presidential podium for the parade. Being a former Soviet republic, Kyrgyzstan speaks not of the second world war but of the Great Patriotic one. The Russian link remains so strong that the president had advanced the date of the parade so he could join President Putin for his great march past in Moscow on 9 May. Standing near us were bemedalled Kyrgyz veterans, wearing their tall, four-cornered Ak-kalpak hats. Among the well-drilled troops was a smart contingent bearing the red, white and blue flag of Russia, a small provocation which caused the British ambassador to stay away. The Kyrgyz flag is red, with a yellow sun whose 40 beams represent the 40 tribes united by Manas, hero of the national epic. The motif on the circle of the sun represents the roof of a yurt. The parade’s atmosphere was solemn but friendly, with low security. It was an interesting moment to be reminded that the larger part of the answer to the famous question ‘Who won the war, then?’ is ‘The Soviet Union’. That pride remains, even in the satellites Communism persecuted. Kyrgyzstan, with China immediately to its east, enjoys Russian protection, and that word ‘enjoys’ may not be wholly inappropriate. In Bishkek, the colossal statue of Lenin has lost pride of place, but is still prominent and well-tended.

Alexandra was leading us to camp and ride in the remote and wildly beautiful Tienshan mountains. Rather than trying to make arrangements for satellite phones, I decided to surrender any direct link to the outside world for a week. The possibility of communication via our leader was also suspended after her horse trod on her mobile phone. The last news we heard before disappearing was that the world had been presented with ‘the first American Pope’. I found this phrase irritating, since he is the second, preceded by the South American Francis. Will a North American one heal, or will his prominence globalise his country’s internal divisions?

The remote regions we traversed remain a largely equestrian society. The few roads are frequently blocked by riders driving great herds of horses, sheep or goats. Our stallion mounts all came from one village, and were accompanied by their owners, also mounted. The charming man who cared for mine is called Melis, which sounds pretty, but stands for ‘Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin’. Melis was born in 1985. Two years later, and I suspect his parents would have called him something else.

I love the power of coincidence. On the third evening, we bivouacked by an astonishingly lovely lake, inaccessible by road. Into the camp walked a young man, uninvited. He was wearing a kilt and carrying backpack and bagpipes. I knew him. The last time I had seen Sacha Murray-Threipland, a student at St Andrews, was in Kharkiv two years ago. As I reported at the time, he had played his pipes to the empty auditorium of that city’s opera house, closed by Putin’s war: ‘Then, standing on the roof beside an unexploded (and disabled) Russian missile, he played “Highland Cathedral” to the crowd below.’ Sacha had been due to meet one of our party in Kazakhstan but had decided instead to try his luck in our region of Kyrgystan. As he passed our camp, he heard English voices. Having walked 25 miles that day, he stayed.

The next day, we rode up a precipitous mountain pass, slow work which involved dismounting as we climbed. Following on foot, Sacha caught up with us shortly after we had stopped at the top to look back at the lake and forward to the still snow-clad peaks on the other side. Out came the bagpipes, and he played ‘Highland Cathedral’ once more, so enthralling the Kyrgyz grooms that they did not notice some of our untethered horses trotting off. Also attracted by the sound were seven lammergeier vultures, circling expectantly. Did they mistake Sacha’s skirls for the sound of an animal in distress, and thus their future lunch?

At night, sometimes accompanied by the maddeningly repetitive call of the scops owl, or at dawn, when the cuckoo often called (we have heard none in Sussex this spring), I lay in my tent and read my fat paperback, Trollope’s He Knew He Was Right. One subplot concerns Hugh Stanbury, a bohemian young journalist for the Daily Record (based on the then new Daily Telegraph) whose heiress aunt cuts him out because of his lowly trade (‘filthy stuff’, ‘printed on straw’). Hugh thinks the decent but uncertain money he earns by this means should not prevent him marrying his true love, Nora Rowley, and argues his case with Nora’s father, Sir Marmaduke, who wishes he pursued a ‘proper’, permanent profession. Hugh’s line is that newspapers – this is the 1860s – are here to stay: ‘Are not the newspapers permanent? – and still more of them always coming out? You do not expect a collapse among them.’ After all, ‘There must be newspapers, and the people trained to write them, must be employed’.

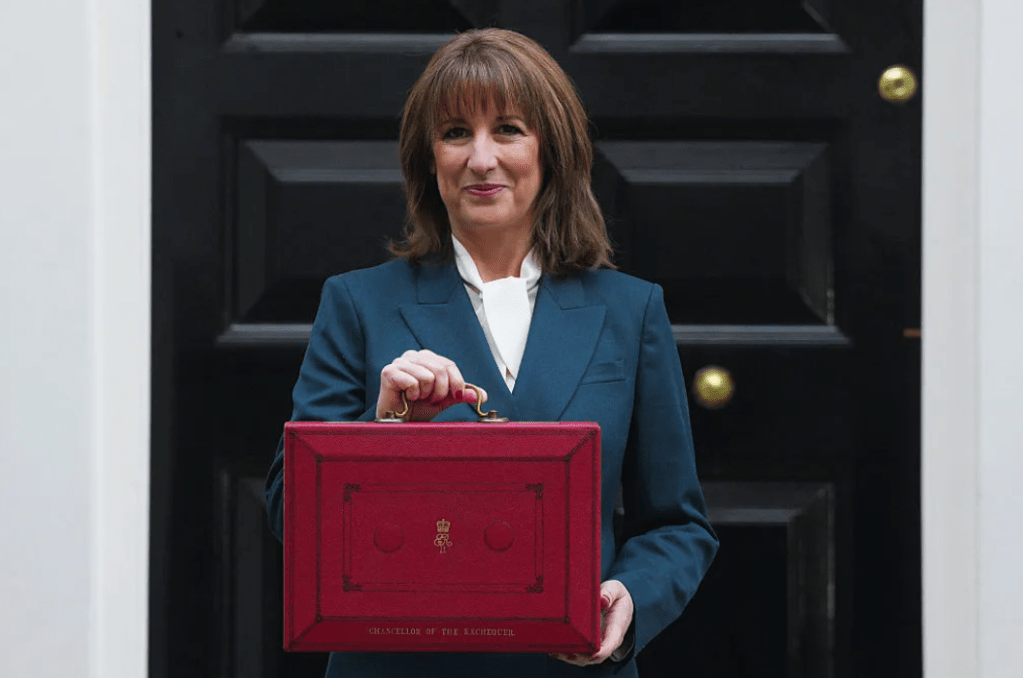

Hugh Stanbury was proved triumphantly right. But what of today, now that the ownership of my employer, the Daily Telegraph, may, after so long, be settled soon? On the one hand, there has never been a time when the media have contained so many possibilities, commercial and creative. On the other, there has never been more uncertainty about where value lies. If you were Sir Marmaduke today, would you try (and, of course, fail) to stop your daughter marrying a newspaper man? On a Kyrgyz mountainside, I found this question no easier to answer than in what used to be called Fleet Street.

Comments