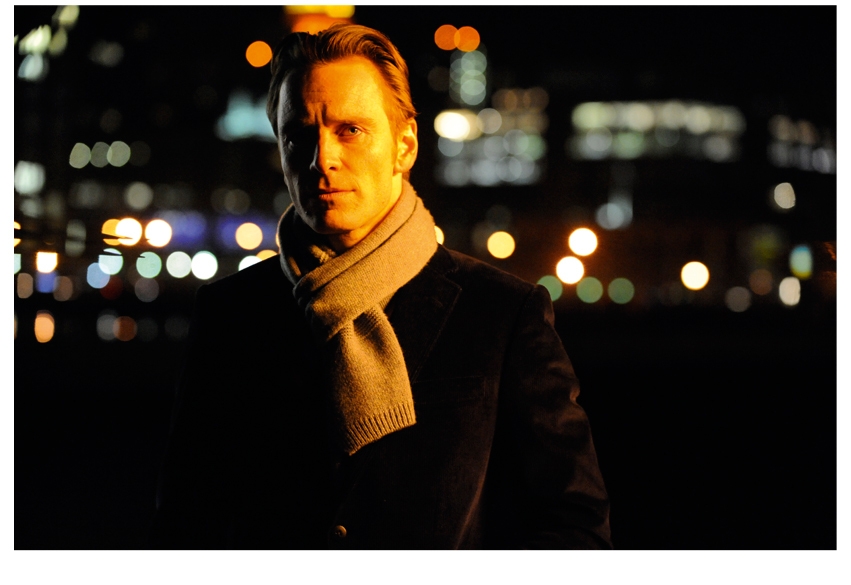

The latest film by the Turner Prize-winning artist and now acclaimed film-maker Steve McQueen is an electrifying snapshot of the life of Brandon, a sex addict, played by Michael Fassbender. Shame (released this week) is McQueen’s second feature and follows his 2008 debut Hunger, about the Irish Republican hunger-striker Bobby Sands, which also stars Fassbender.

McQueen, 42, is west London-born and Amsterdam-based. Intense and passionate, he has a big and bearish presence, and though initially rather brusque, he is none the less in buoyant mood the day I talk to him at the Soho Hotel; the night before, Fassbender had won another award for his performance in Shame, this time from the Los Angeles Film Critics Association — only a few months after receiving best-actor honours at the Venice Film Festival. ‘I’m meeting him tonight,’ McQueen says. ‘He’s going to win a lot.’

After studying at Chelsea School of Art, McQueen attended Goldsmiths College, where he made his first short films. Although primarily known for his black-and-white art installation films, such as Deadpan (a restaging of a Buster Keaton stunt in which a house collapses around McQueen), which won the Turner Prize in 1999, his other work includes photography and sculpture. In 2009 McQueen represented Britain at the Venice Biennale with Giardini, a 40-minute film that minutely captured the life of the city’s municipal gardens.

McQueen’s eye for abstract poetic visuals has been brought to a new level in Shame. In it Fassbender gives an engrossing portrait of Brandon and the ferocious sexual appetite that consumes him. With the arrival of his exuberant but damaged lounge-singer sister Sissy, played by Carey Mulligan, emotional tensions reach boiling point: ‘We’re not bad people,’ Sissy tells her brother. ‘We just come from a bad place.’ Brandon is emotionally imprisoned by his addiction. ‘I liked the idea of somebody who had no control over themselves,’ explains McQueen.

Co-written by McQueen and Abi Morgan, who wrote the screenplay for The Iron Lady, the film is uncompromising. ‘Shame occurred through a conversation between Abi and myself,’ says McQueen. ‘We started talking about the internet and pornography and the conversation snowballed into one on sex addiction — and that was it.’

By day Brandon works in an anonymous office for an anonymous Manhattan company. At night he is strategically pursuing sex in any form and at any opportunity. He eyes up women on the subway, hires prostitutes and visits sex clubs. Despite their intensely provocative depiction of sex, McQueen casually reveals that the scenes were easy to shoot. I am surprised. ‘Really?’ says McQueen. ‘Actors are like thoroughbred racehorses.’

Shame is set in an unfamiliar New York in the dead of winter. ‘In New York virtually everyone is an outsider,’ says McQueen. ‘We pointed the camera where we needed to point the camera. That was it.’ McQueen has a reputation for never compromising.

Shame abandons all visual clichés of New York as the ultimate metropolis of countless films in favour of a bleak, blank cityscape. Faceless buildings are frozen in a steely grey and blue half-light. As a young boy McQueen was in New York during the notorious 1977 blackout, and unsurprisingly it is in the night-time scenes that McQueen’s cinematography comes into its own.

The city is the third central character in Shame. It is somewhere McQueen knows well — he studied briefly at the Tisch Film School at NYU after Goldsmiths College but quit: ‘It was like a Chinese circus. You come out and you can do the splits and everything but as an individual, who are you, what are you?’

Shame has been compared to Bernardo Bertolucci’s controversial 1972 film Last Tango in Paris but McQueen is having none of it. ‘There is nothing to compare,’ he says. ‘It is sex in one movie and sex in another.’ Although he later admits that he did call the character Brandon after Marlon Brando: ‘The physicality of both Michael and Brando is quite similar.’

McQueen continues to draw on the raw physicality of Fassbender’s acting, first displayed in Hunger, in which the actor went on an extreme diet to prepare for his role. Equally arresting in Shame is a scene where the camera follows a naked Brandon’s tense, ritualistic wanderings around his flat. McQueen even manages to make Brandon pissing look interesting.

Hunger and Shame clearly show that McQueen and Fassbender bring out the best work in each other. ‘We have got closer,’ he says. ‘I seem to get the best out of him but I always have to be game. He is a movie star. I’m not.’

McQueen’s next film looks set to be equally challenging and takes him back to the America of the 19th century. 12 Years a Slave, which will feature Fassbender, albeit in a smaller role, stars Chiwetel Ejiofor as a New Yorker who spends more than a decade on a Louisiana cotton plantation after being kidnapped.

While not a political artist, McQueen’s most interesting project came about when he was appointed official war artist for the Imperial War Museum in 2006 and went to Iraq. What emerged was ‘Queen and Country’, a series of postage stamps, each one a photograph of British servicemen who lost their lives in Iraq. It is an ongoing project that has yet to be realised by the Royal Mail but McQueen is doggedly persisting. He was awarded a CBE in 2011.

McQueen doesn’t like being labelled an artist turned film-maker and is reluctant to bring his work as an artist into our conversation. (His latest sculptures will be shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago later this year and in Basel in 2013.) However, the artist in McQueen means that he is still not entirely comfortable about being seen as a commercial film-maker. ‘I’m very surprised because I never think of that when I am making a film,’ he says, adding that the public appetite for serious, provocative films makes it easier for him to accept the label. ‘Sometimes you put your hand in the top hat and you pull out knickers,’ says McQueen with a laugh. ‘Quite often you pull out rabbits.’

Comments