Such was Paul Poiret’s influence that he is the only couturier whose clothes are known to have caused several fatal accidents. At a time (1910-11) when fashion was loosening up he persuaded chic women into the hobble skirt, a garment so narrow round the ankles that only tiny, mincing steps were possible, with the result that several tripped over when stepping down from a pavement and one toppled from a bridge into a river where, unable to swim from the constriction around her ankles, she drowned.

In Mary E. Davis’s book, however, this dangerous garment gets only a brief mention. Instead, what we have is not so much a biography as a well-illustrated study of this extraordinary man through several different aspects of his life – his self-mythologising, his deep involvement in the arts, his unparalleled gift for publicity, his manipulation of celebrity and, of course, his creativity, all immensely detailed and with the context given as much attention as the protagonist. From all this emerges piecemeal the story of Poiret’s life – his rapid, spectacular rise and equally sharp fall.

His great achievement was to integrate fashion into the wider aspects of culture (Davis describes herself as a cultural historian). He knew and befriended many painters, acquiring a notable art collection himself, and he quickly learned the value of seeing his creations worn by actresses on the stage. He always attended first nights at the theatre, opera and exhibitions and gave legendary parties at his beautiful 18th-century mansion; he wrote articles and three large volumes of memoir and was often interviewed, enjoying a long-lasting connection to Vogue. Then, too, unlike the other great couturiers of the day, such as Worth and Doucet, he expanded his business into beauty and perfumes – in short, he turned himself into a brand.

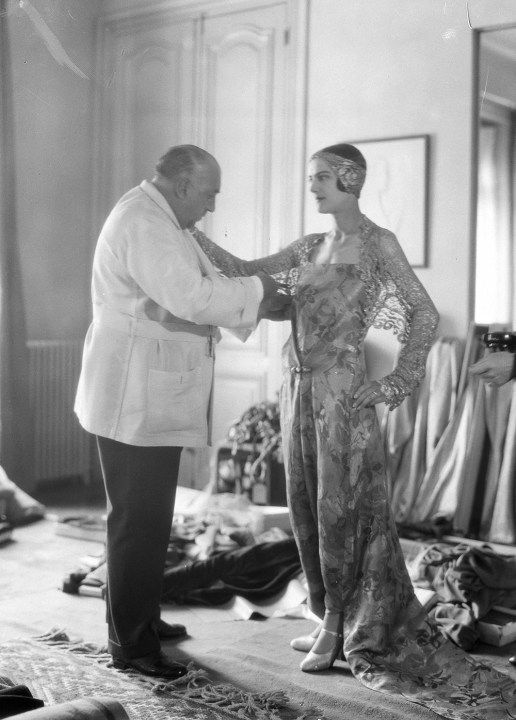

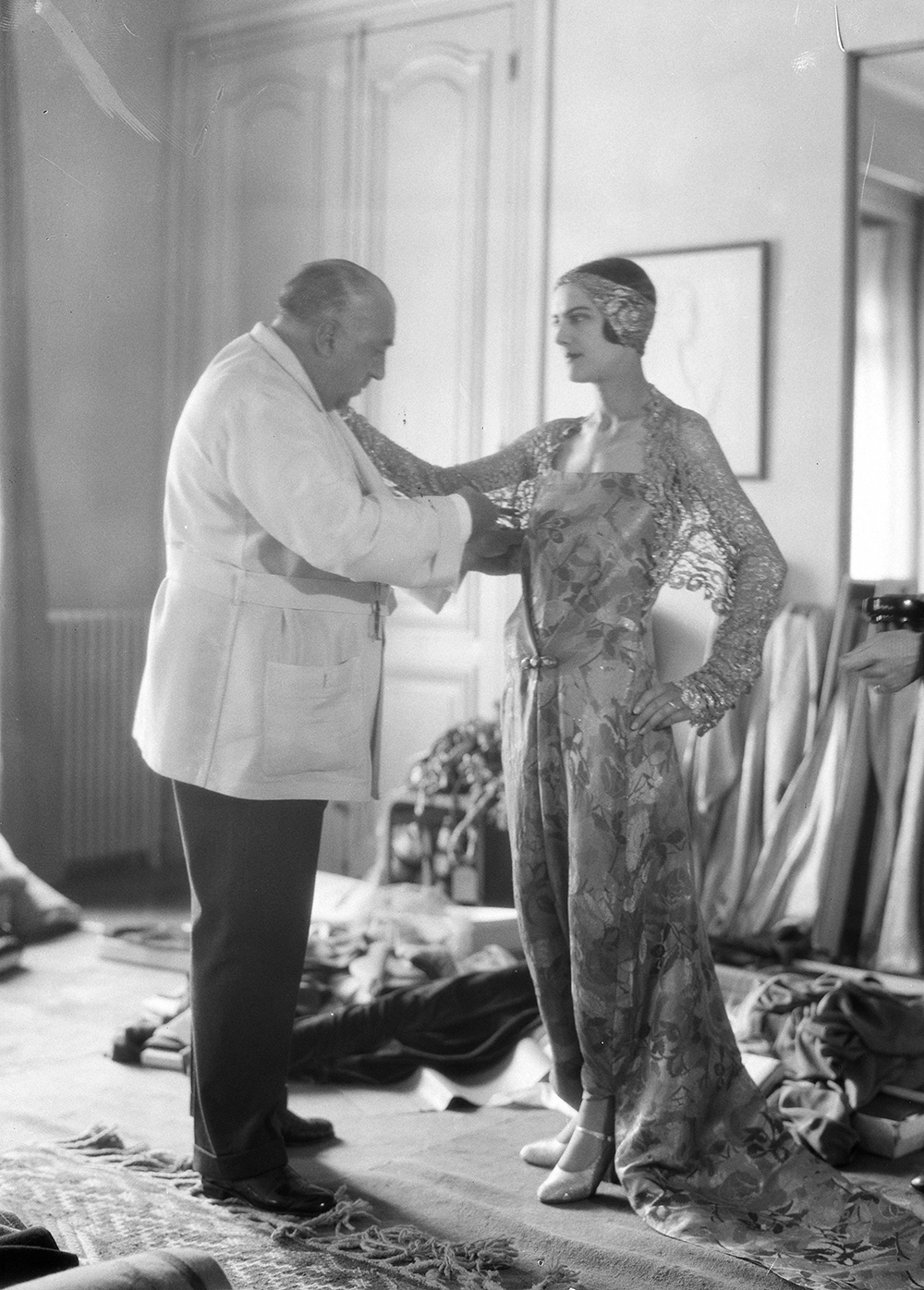

The son of a cloth merchant from the poor area of Les Halles, Poiret started his career with Jacques Doucet, whom he left in 1900 for his year’s compulsory military service. When he returned, he joined the House of Worth. It was there he created one of his most radical designs: the famous kimono coat. Then, in 1903, at the age of 24, he took the brave step of opening his own salon, Maison Poiret, at 5 rue Auber, luring away some clients from his previous employer. Two years later, he married Denise Boulet, a slim, dark-haired 19-year-old from Normandy, with whom he would have five children. For him, the naive Denise was a blank canvas, to be transformed into, as he predicted, ‘one of the queens of Paris’.

In 1908 came the dress that really expressed his philosophy, worn for the first time, naturally, by his slender, beautiful wife. This was a high-waisted gown reminiscent of the Second Empire, hugely daring for its day as it was designed to be worn without corsets – those tight, implacable straitjackets that forced a woman’s body into the then-fashionable S-shape, giving it the impersonal lines of a wooden mannequin. Instead, the new dress allowed the natural figure, especially the bust, to be glamorously displayed. He named the style ‘Lola Montez’, an allusion to the 19th-century courtesan said to have ripped open her bodice when challenged by King Ludwig of Bavaria to show that her breasts were real.

The following year, Poiret was the unwitting cause of a scandal in England. Margot Asquith, the stylish, unconventional wife of the British Prime Minister H.H. Asquith, was so taken with Poiret’s brilliant new designs that she invited him to show them to a group of her women friends over tea at No. 10 Downing Street. This turned out to be a political gaffe of the first order and a gift to the Conservative opposition, with protests from various British clothing associations and an MP’s letter to the Times enquiring about ‘an alleged exhibition of foreign-made articles at the official residence of the Prime Minister… calculated to damage the home manufacturer of similar articles’. Mrs Asquith herself had to reply, stating that Poiret’s models ‘can be bought in any London shop’ (at the time, Debenhams was advertising copies of Poiret tea gowns in velvet).

These years before the first world war saw Poiret at the zenith of his creativity and fame. He had done away with the petticoats and corsets of Edwardian times, putting women into fluid, flowing garments; his name was known everywhere and to his house flocked le tout Paris. But in 1914 came the war; when, after its four years, he returned, his business was debt-ridden and new designers, such as Chanel, were appearing.

For years he struggled unavailingly to recover the glory days. Then, in 1928, there was an acrimonious – and expensive – divorce from Denise, the woman of whom in 1913 he had told Vogue: ‘My wife is the inspiration for all my creations; she is the expression of all my ideals.’ By now he was so much in debt that he was forced to lose his fashion house the following year, give up his beautiful home and move to a small apartment at the top of a Parisian concert hall; shortly afterwards he went on the dole. Fortunately, he had managed to salvage a large stock of excellent wine from his better days.

In the 1930s he wrote his memoirs, created designs for Liberty of London and even opened a new, short-lived fashion house, but all failed. Then he developed Parkinson’s disease and lost the full use of his right hand. There was a sellout sale of his paintings; he paid his bills and left for Saint-Tropez, at the time still a small fishing village in the south of France, where living was cheaper.

Fittingly, the epilogue to this book is devoted to Elsa Schiaparelli, a friend of Poiret’s since they first met in 1924 when, deeply impressed by her style, he gave her one of his coats. It was a bond that lasted through the years – so much so that when he died, in 1944, it was ‘Schiap’ who paid for his funeral.

Comments