Most science fiction writers got the future wrong. That’s OK. We don’t read sci-fi for predictions and, often, books set in the future tell us far more about the times they written in. But two 20th Century authors stand out as both relevant and prescient to anyone living in 2017. The great JG Ballard is one, and Philip K Dick, the other.

While the majority of 20th Century science fiction writers predicted full automation, huge advances in propulsion technology or the colonisation of other planets, Ballard and Dick were visionaries of inner space, telling us what life would feel like for 21st Century (and later) humans. The sense of a body politic spun out of control; of a world where the difference between truth and a lie has been eroded; the depersonalisation of private life and the ever-widening gap between those who can shield themselves from the future, at least temporarily, and those who can’t, looms large in Dick’s magnificently unique and unruly oeuvre.

His novels might not have the best prose, the characters may sometimes be paper-thin and the plots perfunctory – but the explosion of ideas leaping off almost every page makes up for these limitations. In these novels, Dick interrogates the entire discourse of philosophy and theology through the logic of the unravelling future.

His writing straddles many genres, from the proto-Dirty Realism of the 1950s to the hallucinogenic mindwarps of the 1960s, culminating in the fevered theological labyrinths of the later books. Like any good psychotropic, Dick warps your sense of what is real, rearranging your brain like a Rubik’s cube, leaving your relationship to the world fundamentally changed. Here, listed in chronological order, are five of the most seductive gateways into the Dickian world.

In Milton Lumky Territory (1958)

Before he became known as a science fiction writer, Dick tried to write a series of contemporary, realist novels about the struggles of young working class people in 1950s California. These novels, In Milton Lumky Territory in particular, are nowhere near as well known as they should be and are, along with the works of John Fante, the initial wellspring of what would later come to be known as ‘Dirty Realism’ – a movement which showcased such luminaires as Richard Yates, Raymond Carver, Richard Ford and Charles Bukowski. This was the first time American fiction focused exclusively on the under class and Dick bought his own personal frustrations and bad days to bear on its pages. In Milton Lumky Territory is a Southern California analogue to Death of a Salesman, a profoundly moving and heartbreaking deconstruction of the American dream. These realist novels have yet to be properly excavated and given their rightful place within the canon of modern American literature.

Martian Time-Slip (1962)

A strange book, even by Dick’s standards, Martian Time-Slip is set on a bedraggled Martian colony and includes some smart satire on the nature of civic organisation and power politics – but at its heart is a story of schizophrenia and the slippery nature of time. Like all of Dick’s great novels, this one begins small and slowly, the humdrum frustrations of the colonists’ lives not unlike those of the failing businessmen of the realist period – but, as the novel progresses, things begin to turn seriously weird. A profound analysis of mental health and the contingencies of reality, Dick sees autism and schizophrenia as time-based disorders and the tale of Manfred, the afflicted boy, is one of Dick’s most heartfelt and poignant.

The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch (1964)

Probably the most warped and terrifying novel ever written. The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch is a horror story wrapped in a sci-fi tale, encased in a philosophical riddle. Dick is firing on all cylinders in this narrative of lowly Martian immigrants whose lives are so brutal and unremitting that their only escape is through taking a drug which creates communion among its members. When the suitably-named Palmer Eldritch returns from a long journey in space with a new, cheaper and better version of the drug, the colonists swarm to it with hideous results. A meditation on religion, transubstantiation, the nature of time and evil, it is Dick’s empathetic portrayal of working class people trapped in a situation beyond their control which gives the novel its power. It also has one of the most shocking and vertiginous endings ever written, like Borges on acid.

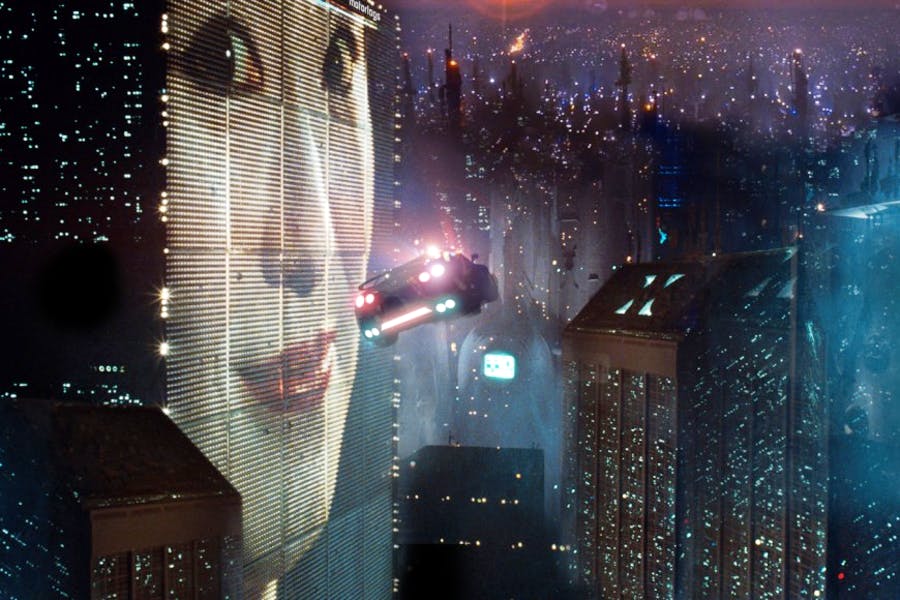

Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1966)

Famous for its adaptation as Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? is one of the author’s most satisfying works. Using the template of the private eye novel, Dick wants to ask what makes us human? And, more pertinently for 2017, what is real and what is fake? In a world where animals have become almost extinct, bounty hunter Decker keeps an electric sheep on his roof as a status symbol, hoping the neighbours will take it for real. The important and integral sub-plot of Mercerism, a new religion which promotes empathy, was totally left out of the original film, thus depriving Decker’s odyssey of its necessary and essential counterpoint. A book of sublime grace and theological depth, powered by a raging anger at those who would destroy humanity in the name of humanity, it stands as one of Dick’s most melancholy and elegiac works.

A Scanner Darkly (1973)

Possibly the best book about the intoxicating grace of drugs and the price our bodies and minds pay for their abuse. It’s also wickedly funny, massively disturbing and one of the deepest investigations into the ‘self’ in literature as well as being a superb private eye novel in which the detective ends up investigating himself. With some of Dick’s best prose, A Scanner Darkly reads as one of his most heartfelt books, made clear by the long end-of-book dedication to friends recently fallen from drugs. Well served by the Richard Linklater film, Dick envisions a hellish modernity where chain stores render every neighbourhood an exact simulacrum of the next. The hilarious ‘bike gears’ conversation was referenced in a homage by Thomas Pynchon in Inherent Vice, a novel that shares a lot of attributes with A Scanner Darkly.

Comments