A campaign is currently underway to have Bristol’s Colston Hall renamed because Edward Colston was a slave trader. This has set me thinking. How gross does someone’s moral turpitude have to be before memorials to him are considered ripe for removal?

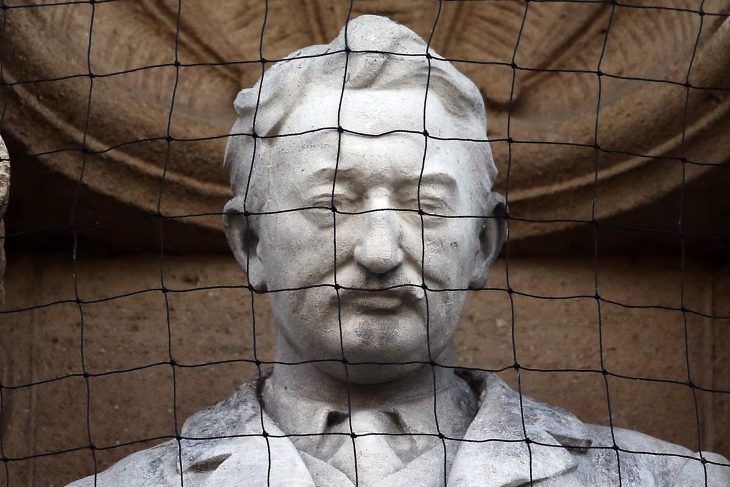

Two years ago, the Rhodes Must Fall campaign successfully lobbied for the removal of a statute of Cecil Rhodes from the campus of the University of Cape Town. The campaign then spread to Oxford, of which Rhodes was a graduate and at which he endowed the scholarships that bear his name. Rhodes was targeted as an architect of repressive anti-black colonialism. But not everything that was done in the name of colonialism was necessarily bad. In 21st-century terms, Rhodes harboured racist views. But he also said that: ‘I could never accept the position that we should disqualify a human being on account of his colour’. And as well as endowing the Rhodes Scholarships he laid the foundations of modern South Africa’s physical infrastructure. Oriel College was right to reject calls for the removal of his effigy from its facade.

The campaign then moved on to other participants in the slave trade. All Souls College was targeted because its library was endowed by Christopher Codrington, a wealthy slave owner. More recently, Bristol University has received the attentions of Rhodes Must Fall activists because it received funding from the Wills tobacco company, which imported slave-grown tobacco right to the end of the American Civil War.

Slavery was a cruel and odious institution. Does that mean that institutions that benefited from its profits must be made to atone by agreeing to engage – now – in acts of public abasement and contrition? And how far up (or down) the scale of gross moral turpitude are devotees of Rhodes Must Fall prepared to go? They do seem to me to have been curiously selective in their choice of targets.

Take Oliver Cromwell, who delighted in massacring Catholics. There’s a statue of him outside the Houses of Parliament and a still working steam locomotive bears his name. I know of no campaign to remove the statue, let alone rename the loco. Or there’s ‘Clive of India’, of whom an imposing statue stands just off London’s Whitehall. Robert Clive, Commander in Chief of British India in the late 18th century, laid the foundations of Britain’s India Empire. Did you know that he perpetrated what would now be called atrocities against the native population, gathering to himself a personal fortune as he did so?

Or how about Martin Luther King Jr, a hero of the American civil rights movement. Granted, King was a charismatic orator. He was also an intellectual thief – a serial plagiarist, who plagiarised about two-thirds of his University of Boston PhD thesis and much else besides, including, some say, his famous ‘I have a dream’ speech. But Boston, while admitting his academic transgressions, has declined to rescind the doctorate. King continues to be positively extolled by student movements the world over. (The proofs of King’s multiple plagiarisms may be found in Theodore Pappas’ Plagiarism and the Culture War: The Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Other Prominent Americans, published in 1998).

Last year a statue of Lord Byron was unveiled near my home in Seaham, County Durham. Nobody seems to have minded that Byron, apart from being a poet of some note, was also a sexual philanderer (not caring whether his lovers were women or men) whose conquests apparently included adolescent boys. Then take Simon de Montfort, the 13th-century Leicester-based warlord who – having called two directly elected parliaments into existence – is widely regarded as a founding father of parliamentary democracy. Not only is Leicester littered with effigies in his honour. An entire university is named after him. But in 1231 Simon ordered the expulsion from Leicester of its entire Jewish community. Have you heard of any student agitation demanding that De Montfort University be renamed? No? Neither have I! Nor, incidentally, have I ever heard anyone speak in defence of a student accused of academic dishonesty by offering the argument that though the student undoubtedly plagiarised, he/she was known to perform good deeds and so – for that reason – should go unpunished.

I commenced my studies at Oxford in 1962. I came there from a working-class Jewish family in Hackney. I recall going into my college dining hall, upon the walls of which were portraits of the medieval Roman Catholic dignitaries who had founded the college. I said in a loud voice: ‘I’m here in spite of you!’ Then I moved on with my life. Adherents of Rhodes Must Fall should do the same.

Geoffrey Alderman is a British historian

Comments