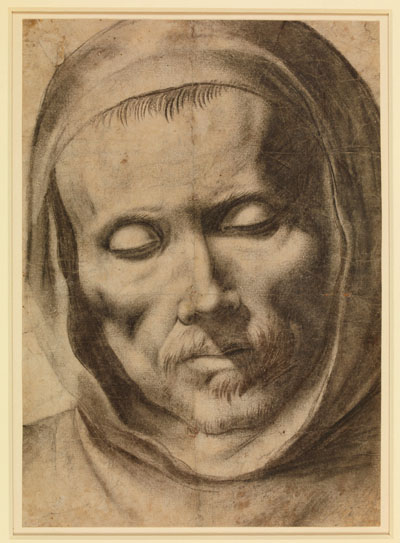

Renaissance to Goya: Prints and Drawings from Spain opens well with a superb drawing by Zurbarán, ‘Head of a Monk’, and a Goya lithograph, ‘The Bulls of Bordeaux’. After that, turn left into the main print room and the disappointment starts. Have you ever wondered why we are not familiar with more Spanish artists than the few great names?

On the evidence of this exhibition the answer is clear. The lesser names are simply not very good, so it is a relief to find the Italian Federico Zuccaro, a working visitor to Spain, among the likes of Vicente Carducho and Miguel Barrosso. However important a historical survey, this show only intermittently comes alive. In a corner, there’s a Velázquez of two horses — one of the very few drawings by him in existence — and lots of oddities are scattered about, such as Francisco Rizi’s black chalk drawing of the dwarf Lusillo. But the sensitive should really try to avoid the awful things by Francisco Herrera the Younger.

The exhibition suddenly changes gear with a run of Murillo images: from ‘St Anthony of Padua and the Miracle of the Irascible Son’, one of his earliest drawings, and St Isidore of Seville, slightly sweet in tone, to the more martial Archangel Michael. Quality dips again until we encounter Ribera, represented by several good things including two exquisite chalk drawings. Then Goya finally comes to the rescue. The comparison offered by an ink drawing and etching of ‘The Garrotted Man’ alone makes the show worth visiting, but there’s more. In fact, lots more Goyas — be careful not to miss the whole section to the right of the vestibule behind Michelangelo’s great ‘Epifania’ cartoon. Here is a matchless array of Goya prints and drawings, including a red chalk portrait of Wellington, a witty Don Quixote beset by monsters, and a chalk study of lunatics. Extraordinary. Meanwhile the accompanying publication by Mark P. McDonald (paperback, £25) is a book rather than a catalogue, a weighty tome packed with scholarly minutiae for the seriously interested.

Stephen Chambers (born 1960) is one of our most accomplished and inventive printmakers, but he is best known as a painter, so it’s rare that we get to see an exhibition (particularly in a public gallery) devoted to his prints. This is why the occasional series entitled Artists’ Laboratory, in the Weston Rooms of the Royal Academy, is such an excellent idea — it encourages RAs to show the less-familiar aspects of their work. In Chambers’s case, he has risen dramatically to the occasion and made an enormous print which overlaps the main wall of the Large Weston Room. Entitled ‘The Big Country’, after William Wyler’s 1958 western, it is an evocation of the pioneers’ experience of opening up America for settlers. It is composed of 78 same-sized screenprinted sheets, individually framed in Perspex, arranged somewhat eccentrically over the wall, some abutting, others leaving gaps and forming clusters. Chambers says the image grew from drawings like a coral reef, and is all about the dark puncturing the light, as people get in among the open spaces.

In some senses, it’s a map of migration, with the names of the ports of embarkation entwined with the imagery. Chambers calls it ‘a lot of vignettes and a lot of moments’, but there is an overarching pattern and coherence to this epic, though by no means a straightforward narrative. Chambers is a brilliantly decorative artist, one of whose strengths is strong colour. ‘The Big Country’ is limited to cream and grey (or black), in elegant dispositions. Notice the trees clumped together like light bulbs through the central section, and the mind-warming intricacies of the ground pattern. Large guardian figures at either end gesture poignantly. This is a work to ponder. On the opposite wall is another sequence: 20 etchings on the theme of impossible liaisons between historical and fictional characters. Chambers calls it ‘my dating agency from Hell’, and the encounters do have a somewhat combustible feel. More work in the smaller gallery completes this partial survey of Stephen Chambers, printmaker, and very impressive it is too.

In the old Museum of Mankind galleries in Burlington Gardens is an exhibition which brings together work by current Royal Academicians to be auctioned to raise money for what is called the Burlington Project. The Academy has been in possession of these marvellous galleries for years now without knowing quite what to do with them. Temporary solutions have been to rent them out or use them for the occasional RA extravaganza, such as this one. But the management has yet to work out how to get the public from one side of the building to the other, so if you’re visiting a show in Burlington House and want to see RA Now, you have to walk right round the outside — via Bond Street or Burlington Arcade — rather than go through the middle. Furthermore, there’s an admission charge of £8, and the day I went the huge galleries contained only a handful of visitors.

This is quite a different show from the annual Summer Exhibition, in which we see Academicians’ work hanging next to non-Academicians’. This is exclusively the membership, though not all the members are showing: the sculptor Ralph Brown and the painter Ian McKeever are for some reason abstaining. The show’s overall effect is sobering, if only to remind us what a roll-call of distinguished contemporary artists have accepted nomination to the Academy. However, it is a generally enlivening exhibition, put together with considerable flair by Allen Jones, and offers a very wide range of artistic expression. But how predictable is it? Try going round the galleries without reading the labels. How many artists couldn’t you guess?

And, finally, a last chance to see The Age of Thomas Rowlandson, a marvellous collection of watercolours and drawings by the master and some of his contemporaries at Chris Beetles Gallery. Rowlandson (1756/7–1827) is one of the great geniuses of watercolour in combination with a potent ink line, often used for humorous satirical effect, but occasionally employed to depict an idyllic landscape. Human folly was Rowlandson’s great subject, and he was particularly given to the excoriation of the seven deadly sins, with lust a speciality. (‘The Parson and the Milkmaids’, ‘Beauty and the Beast’ and ‘The Virtuous Chambermaid’ are all unforgettable.) He was also good on the foibles of society, whether it be the fashion for artificial flowers, or artists drawing pretty girls from life. Over half the works come from a private collection and are wonderfully fresh. Recommended.

Comments