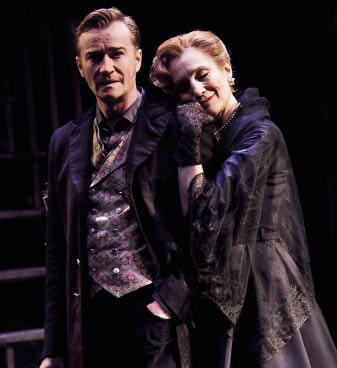

Women Beware Women

Olivier, in rep until 4 July

Hair

Gielgud, booking until January 2011

Women Beware Women deserves a subtitle: spectators beware seldom revived classics. Thomas Middleton’s 1622 play is set in the duke’s court at Florence, where greed, lust, incest and the hunger for power are running rampant. Middleton is much admired, little adored. He’s one of those dramatists who sends actors, directors and literary professors into rhapsodies but who doesn’t attend to the basics of entertainment. There’s no central character in this play just a grand human theme, corruptibility. He wraps up the script in great cobwebby entanglements of interrelated storylines. In one thread we follow a character named Bianca, who starts as a demure young wife, is raped by a count, becomes his mistress and ascends from blameless gentility to a compromised position of wealth and influence. But at no point during this huge journey did I feel touched or moved by her transformation because Middleton’s grasp of character is far less certain than his knack for lyrical invention.

He subordinates every element of his play to the polished elegance of his wit, and all of his characters, even the servants, speak in exquisitely turned poetical dainties. Look at this. ‘Sin tastes, at the first draught, like wormwood water/ But drunk again ’tis nectar ever after.’ One could write quite a lengthy monograph on the gorgeous offbeat symmetries of that extraordinary couplet. The ingenious placings of ‘draught’ and ‘after’, ‘water’ and ‘nectar’ provide the ear with a pair of internal harmonies that leave the fleeting impression of rhyme but without the jangling tricksiness of a true rhyme. This is Middleton at his finest and the play is best enjoyed in excerpts and fragments. It’s like a beach of pebbles. Individual stones reward close study but laid out in its full extent all you can see is a mass of shiny greyness.

A sprawling, difficult drama like this would benefit from concision and clarity but the director Marianne Elliott heads in the other direction, for exuberance, complexity and ingenuity. Some of her effects are simple and tasteful, others cumbersome and overly conceptual. The acting covers an astonishing range from the sublime to the brutish. Harriet Walter plays a scheming courtier with a degree of grace and poise that comes close to perfection but she’s supported by a set of misfiring clowns who think that comedy is a matter of distorted gestures and vocal absurdity. Comedy is the nirvana of acting. To get there you need to start from your destination.

In the closing ten minutes of this lumbering play Elliott lays on a tour de force, a heavily choreographed ballet of murder and revenge accompanied by skirlings from a jazz quintet (which Middleton seems to have omitted from the stage directions in my edition of the play). The actors prowl the shadows in masks. Chandeliers descend from on high. The set twirls round. Someone gets stabbed. The set twirls round again. Someone else gets stabbed. Up go the chandeliers. The set twirls round again. Down come the chandeliers. Another stabbing, and so it goes on. For all its acrobatic precision and meticulous stylishness this bizarre cabaret lacks any impact because the detailing is too fanciful and overwrought and it slows the action just when acceleration is needed. After 140 minutes of literary elegance the audience wants a quick bloodbath and a taxi home.

A triumphant Broadway revival of Hair has arrived in Shaftesbury Avenue. Like the hippies themselves the show is effervescent, bawdy and a bit annoying all at once. Its great achievement is to capture the spirit of 1967 and to remind us that beneath the hippies’ ebullience and love of pleasure lay a certain self-righteousness and petulance. The flower-power movement was blissfully and fatally free of self-criticism. It never understood, let alone acknowledged, its inherent contradictions. It promoted escapism as reality and forgetfulness as a higher variety of awareness. And it wanted to live in two timescales at once: instant hedonism that would last for ever. I was at nursery school in 1967 so the nostalgia reflex isn’t there for me but the stalls were jam-packed with ladies of 70 or over, in knitted cardigans and stately grey hairdos, their silk neck scarves knotted at their throats and their prim spectacles perched on the ends of their noses and they were roaring with laughter at the dope references, the knob gags and the anal-sex routines.

I was faintly slightly scandalised by it all. Perhaps it’s a generational thing but I found myself wondering if these old hippies are ever going to grow up.

Comments