It’s hard to admire communist art with an entirely clear conscience. The centenary of the October revolution, which falls this month, marks a national calamity whose casualties are still being counted. When my father-in-law comes to visit, I have to hide my modest collection of Russian propaganda: he grew up under the Soviets and has few fond memories of the experience. He can’t work out why old agitprop is so popular today. But the simple fact is, for all the disaster they wrought, the Bolsheviks did leave a legacy of images so striking that, even now, they can draw thousands into a museum. As Tate Modern is about to demonstrate.

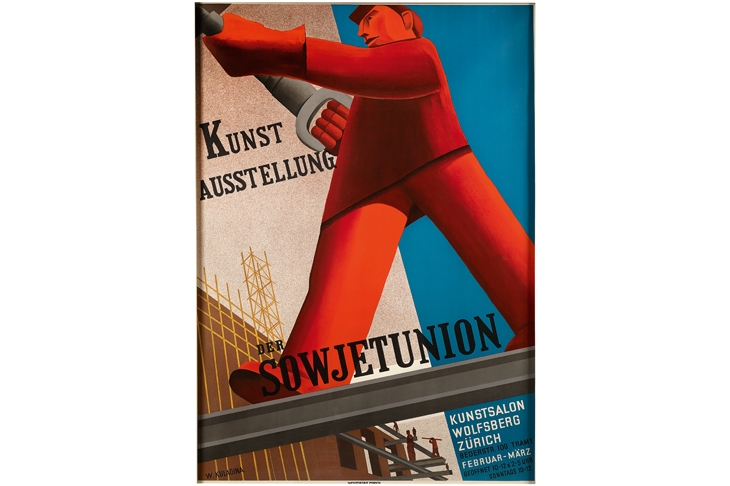

Its new exhibition, Red Star Over Russia, showcases one of the greatest collections of Soviet propaganda posters. It’s the work of a former Sunday Times journalist, David King, who fell in love with the genre and spent decades recovering posters that the regime discarded. Normally, art helps illustrate history — pictures to go with the words. But in Russia’s case, only art can tell the full story.

Russia’s artistic revolution was underway long before Lenin’s. St Petersburg had become a cauldron of radicalism by the turn of the 20th century, with poets, playwrights and artists discussing the fall of tsarism and what should replace it. They were inspired not so much by Marx but by a present where everything, art especially, was breaking free from old confines. By the possibilities of new technology, a future of female empowerment, flatter hierarchies and modernity.

For Kazimir Malevich, rejecting the ‘dead weight of the real world’ meant depicting not people or things but a new, ideal world of shapes and forms. He called his style ‘suprematism’ as it celebrated the supremacy of geometry over reality.

Kazimir Malevich – Aeroplane Flying, 1915

He’d often use only two or three colours, most famously just black and white in his ‘Black Square’, exhibited in St Petersburg in 1915. Lenin, who seized power two years later, had no interest in art or aesthetics. But when the resistance to the Bolsheviks led to civil war, they needed new tools of propaganda — to explain to a largely illiterate country what (and who) they were fighting for (and against).

The war effort led to the creation of Rosta in Moscow and St Petersburg, a news agency that doubled as a Bletchley Park for propaganda. It enlisted not just artists but also futurist poets such as Vladimir Mayakovsky, who became one of the project’s most enthusiastic advocates. They were asked to make as many posters as possible, hundreds a week. Stencils would be used, so posters could be painted rather than printed. The suprematist style of using a limited range of colours was to become a trademark of the Soviet poster. A total of 3,130 posters were produced in the civil war years: a third military, a quarter political and the rest economic or cultural.

Vladimir Maykovsky: futurist, poet, propagandist

To the 25-year-old Mayakovsky, this project was about art breaking free from galleries and speaking to the nation, like Bolshevism itself. It meant ‘a nation of 150 million being served by hand by a small group of painters’, he wrote. As a result, soldiers could see the posters then join battle ‘not with a prayer on their lips, but with a slogan’. Trains ferried agitprop posters (and lecturers) to newly ‘liberated’ territories — talking about the enemy, about the revolution, about women voting, about the Russian soul.

Take perhaps the most famous Soviet poster: El Lissitzky’s ‘Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge’ (1919–20). A version of it hangs in the Spectator’s offices. There are no faces, no landscapes, just a long red triangle (the Soviets) piercing a white circle (the counter-revolutionaries) with other lines and rectangles floating free.

Even now, it looks fresh and urgent — but like all suprematist art, the shapes could be taken to mean anything. My adapted version of ‘Red Wedge’, for example, depicts Charles Moore, Rod Liddle and Taki defeating the forces of cliché, mediocrity and boredom.

Posters were being made the world over by 1919, but none had the immediacy or power of those coming out of the Soviet Union. Rosta knew how to mix art and adrenaline. At a given signal, Rosta artists would be asked to hurl themselves at a sheet of paper to see who could complete the task first. The reception was lively and positive. Crowds regularly gathered around newly issued posters. Soldiers would send messages back saying, ‘Give us more caricatures of priests, of whom we have had enough.’ The Whites, who had also attracted Russian artists, tried posters — but they were too text-heavy and, therefore, ineffective. Mayakovsky often said that a Soviet poster was a failure unless it could bring a running man to a halt.

The Rosta artists had much creative freedom. By no means all of them were communists, which started to show when some of the political posters went wildly off-message. The daring didn’t always impress the Politburo: one member complained that the prolific Dmitry Moor’s posters had so much blood that they’d run out of red ink.

Moore’s love of red made the Politburo worry that they’d run out of black paint

Moor was declared a ‘hero of the pencil and the paintbrush’ after the war, but in general it was felt that the artists needed to be brought to heel. One contemporary account describes an old woman looking at a poster drawn in the cubist style, featuring a giant fish eye, and proclaiming, ‘They want us to worship the devil!’ Lev Kamenev, one of the most senior Bolsheviks, lamented ‘a kind of student exercise in the fashionable futurist style’ that ought to be shut down.

After Lenin’s death, Stalin obliged. He wanted the Kremlin’s writ to cover everything, and oversaw the new, crushingly dull orthodoxy of Soviet realism. Artists had to play along or go underground, holding exhibitions in each other’s houses or the park — and praying the KGB wouldn’t find out. The second world war saw a reprisal of old posters (and, sometimes, their artists) but the poster never regained the artistic heights of the first few Soviet years. The best work, done by nonconformists, forms the most diverse, powerful and moving genre in all of Russian art.

When David King’s poster collection was being moved into Tate Modern in preparation for this exhibition, the box labels rather summed it all up: ‘gulags’, ‘famine’, ‘great terror’, etc. This, more than anything else, is the Soviet legacy. But for those who wonder how anyone could ever have been optimistic about it, this exhibition offers part of the answer — conveying the sense of romance, heroism and artistic optimism of the early years. It looks all the more powerful, now that we know how it all ended.

Comments